The Best Player in Baseball Doesn’t Want to Be a Superstar – The Ringer (blog)

A big league clubhouse during pregame media availability can be a lonely place. Players sit in front of their lockers, by themselves or in small groups, getting changed or unpacking equipment or just looking at their phones, while reporters stand around, most of them waiting to have specific conversations with specific players, who might or might not be in the room. Those conversations last a couple of minutes each, and then everyone goes back to standing around.

A big league clubhouse during pregame media availability can be a lonely place. Players sit in front of their lockers, by themselves or in small groups, getting changed or unpacking equipment or just looking at their phones, while reporters stand around, most of them waiting to have specific conversations with specific players, who might or might not be in the room. Those conversations last a couple of minutes each, and then everyone goes back to standing around.

Some clubhouses have a little more of a party atmosphere, thanks to a centrally located ping-pong table or video game console, but the Los Angeles Angels’ locker room at Tempe Diablo Stadium in Tempe, Arizona, is comparatively spartan. With temporary lockers set up in the middle of the clubhouse to accommodate the larger spring training rosters, there wouldn’t be any room for a ping-pong table anyway.

Players who want to avoid the reporters quickly learn how: They stay in off-limits areas like the weight room or trainers’ room. Albert Pujols, for instance, popped in and out of the clubhouse, but did so with purpose; he’d grab a bat, then disappear, then come back a few minutes later for a towel, all without saying much more than, “Good morning.”

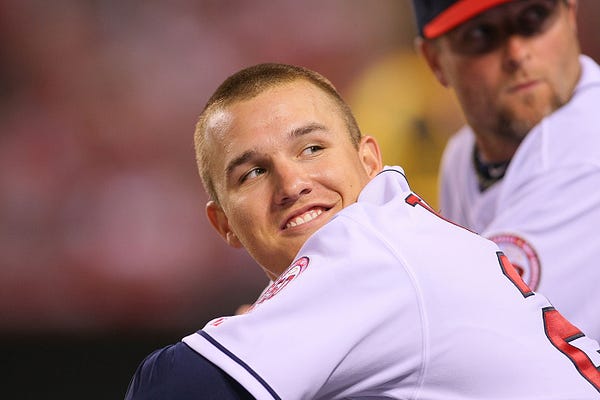

Center fielder Mike Trout didn’t spend much time in the clubhouse proper, but he spent almost all of it talking to people — a quick chat and a handshake with an Angels PR staffer, a laugh with nearby teammates, and then a series of those four- or five-minute conversations with reporters. Trout stood by and answered every question dutifully but succinctly, mindful, as the best player in baseball, of how in-demand he is.

“I just want to be a guy people like,” Trout told me. “Kids like me, and I just [want to] respect the game.”

People do seem to like Trout — a lot.

“He’s just so engaged. He’s an amazing athlete, the power’s unreal, he’ll go after the ball in the outfield — he’s just special,” said Angels outfielder Ben Revere. “But the main thing is he’s a humble kid. That’s what everyone appreciates about him. He doesn’t go out there and showboat. He just goes out there and does the business and lets his game talk.”

“Mike’s the greatest, he really is,” said Angels reliever Cam Bedrosian. “He just goes about his business, day in and day out. You know he’s going to put on a show, and there’s just something special about him.”

Just this week, ESPN’s Buster Olney started a story about Trout’s idea to rotate umpires during spring training with this line: “Mike Trout is widely regarded as baseball’s best player, and you’d be hard-pressed to find a player who is more universally liked than Trout.”

“Behind the scenes, what you see is what you get,” said Trout’s agent, Craig Landis. “Mike’s one of the nicest, most polite and humble stars I’ve ever seen.”

But Trout is of a class of athlete that usually aspires to be more than just “liked.” He’s left his peers in baseball behind, and in terms of on-field success, is in a class with the likes of LeBron James, Lionel Messi, Tom Brady, and Cristiano Ronaldo. These are not only the best athletes of their generation, but possibly the greatest of all time in their respective sports.

Unlike those players, Trout comes without baggage. He doesn’t carry the sheen of Patriots evil like Brady, Ronaldo’s pretty-boy image, Messi’s suspended jail sentence for tax fraud, or … whatever it is people don’t like about LeBron.

Trout’s only public scandal came in 2015, when he tweeted support for Floyd Mayweather before the serial domestic abuser’s title fight with Manny Pacquiao, a mistake seemingly made out of naïveté more than anything else.

Apart from that … well, during spring training he told me his go-to Wawa order is chicken noodle soup.

After living in New Jersey for 21 years, I had never met someone who routinely went to Wawa — the Mid-Atlantic convenience store mecca, home to Hoagiefest, the best gas station coffee on the planet, and quart jugs of iced tea popular among construction workers and high school students — and routinely ordered soup. I looked at Trout the way Texans look at me when I tell them the most important part of barbecue is the sauce, and pressed him for an explanation.

He had none. “I like the chicken noodle soup,” he repeated. And that was that.

Trout has no public feuds to speak of, no memorable quotes, no social media hashtag, no non-sports IMDb credits. The next step for an athlete of Trout’s stature would be to become the kind of celebrity who transcends the sport, like LeBron or Michael Jordan, but entering his sixth full season in the big leagues, he hasn’t shown any interest in doing so.

Trout’s career feels less remarkable than it is because we’re living through it, as if the ominous and inscrutable alien spaceships from any number of sci-fi stories just showed up and we went about our business like nothing was wrong. To appreciate Trout, you really have to go back and grapple with him every so often.

Trout’s career feels less remarkable than it is because we’re living through it, as if the ominous and inscrutable alien spaceships from any number of sci-fi stories just showed up and we went about our business like nothing was wrong. To appreciate Trout, you really have to go back and grapple with him every so often.

The first remarkable thing about Trout is how big he is. At listed dimensions of 6-foot-2 and 235 pounds, Trout isn’t as bulky as The Mighty Giancarlo Stanton. He’s not incredibly tall for a ballplayer, either, and he doesn’t have quivering Disney bad-guy muscles popping out from under his uniform. Trout just looks big, the way a truck or an office building is big. Despite that, he’s unbelievably light on his feet — fast, but not bouncy, leaning forward as he chops down the baseline like a steampunk helicopter.

Unlike his contemporaries within baseball, like Bryce Harper, or in other sports, like Messi or James, Trout was relatively unknown as a youngster. The son of a minor league ballplayer, Trout grew up in the Philadelphia exurb of Millville, New Jersey, a part of the country not known as a prep baseball hotbed. South Jersey produces its fair share of talented ballplayers, but most of them are from shore towns, like 2016 Red Sox first-rounder Jason Groome, or were college products, like Trout’s Angels teammate Andrew Bailey and A’s reliever Sean Doolittle, or, in the case of White Sox third baseman Todd Frazier and longtime big league pitcher turned Mariners GM Jerry Dipoto, both.

Top high school prospects tend to come from warmer climates, which allow them to play baseball year-round, and that has three effects that professional teams like: First, it allows scouts to get more looks at players before the draft. Second, the added reps cause those players to develop more quickly (though that can also come hand-in-hand with pitcher overuse). Third, the overall quality of play is higher, which makes it easier to scout. For example, there were seven high-schoolers from Atlanta or its suburbs taken in the first two rounds last year; a scout could not only see four or five of them in one weekend, but he could also see them play against each other. In Trout’s draft year, scouts would’ve had to make a special trip to see him hit off pitchers throwing with velocity in the 70s, and even then the weather doesn’t always cooperate. Part of the Trout creation story is that New Jersey had a particularly rainy spring in 2009, so scouts had an even harder time pinning down when he was going to play.

So, most high school prospects from New England and the Mid-Atlantic go to college to develop — Maryland, North Carolina, Vanderbilt, and Virginia all recruit the area heavily — and some of them, like the Blue Jays’ Marcus Stroman and the Mets’ Matt Harvey, eventually strike it rich as college first-rounders.

Trout is probably the second-best position-player prospect of the draft era to go pro straight from a South Jersey high school, and the final reason he was such an anonymous amateur prospect is what happened to the one person ahead of him on the list.

Billy Rowell was a shortstop and third baseman for Bishop Eustace Prep in Pennsauken, a laboratory-created 6-foot-5 slugger who was named the National High School Baseball Coaches Association player of the year in 2006, one year before Mike Moustakas and one year after Justin Upton. (Other previous winners include Alex Rodriguez, Josh Beckett, Adrián González, and Joe Mauer.) The Orioles picked Rowell ninth overall that year, thinking he was the next Cal Ripken, and Rowell busted spectacularly, flaming out after 41 games at Double-A.

So when Trout came along three years later, Rowell was three hours down the road in Frederick, Maryland, where he would hit .225/.284/.336 in his second trip through high-A, flashing like a giant caution sign over any South Jersey high school prospect.

The Angels took Trout at no. 25 anyway, signed him quickly, and sent him to rookie ball, where he quickly proved to be the anti-Rowell. After graduating high school at 17, Trout hit .352/.419/.486 in his first year, then hit .341/.428/.490 across two levels in 2010, against much older competition, good enough for both Baseball Prospectus and Baseball America to name Trout the second-best prospect in baseball behind Harper.

In 2011, Trout debuted with the Angels at age 19, making a 40-game cameo in which he struggled for the first time as a pro, hitting .220/.281/.390, but when Trout returned to the big leagues late the following April, he was the best player in baseball from the moment he stepped onto the field.

“God is going to take credit for Mike Trout,” Angels manager Mike Scioscia once said, “not anything we’ve done.”

Can a baseball player even become an international icon in this fragmented and often unforgiving media culture? Baseball is long and slow — baseball people keep telling us so themselves. Plus, nothing would fit the “baseball is boring” narrative better than the game’s biggest star’s most controversial opinion being about soup and his primary image concern being a desire to set a good example for kids.

Can a baseball player even become an international icon in this fragmented and often unforgiving media culture? Baseball is long and slow — baseball people keep telling us so themselves. Plus, nothing would fit the “baseball is boring” narrative better than the game’s biggest star’s most controversial opinion being about soup and his primary image concern being a desire to set a good example for kids.

While baseball is certainly an international sport, so is ice hockey, and nobody’s asking where Sidney Crosby’s $50 million shoe deal is. LeBron, Messi, and Ronaldo — and before them, Jordan, Pelé, and Maradona — are worldwide, larger-than-life figures because basketball and soccer are truly global sports. Baseball can put together an international tournament with teams from 16 countries, but it has mere footholds in South America, Europe, and mainland Asia, and no presence to speak of in Africa.

Trout didn’t make Forbes’s list of the 100 highest-paid athletes last year, though he likely will in 2018, when his salary will jump to $34 million and change. That’s partially because baseball’s salary structure punishes young players for being young, but baseball players also have a certain natural ceiling because they don’t get the endorsement deals common for basketball or soccer players, or individual athletes like golfers and tennis players. Clayton Kershaw was the top MLB player at no. 33.

Although no current baseball player has broken through that ceiling, that’s not to say it can’t be done. It wasn’t so long ago that Ken Griffey Jr. was that kind of superstar. It just takes that once-in-a-generation combination of personality and talent, and for as cool as Griffey was, Trout is a much better ballplayer, and possibly even better liked within the game.

One reason baseball hasn’t seen a star like Griffey in the past 20 years, though, is that between the 1994–95 strike and the steroid era, baseball is only now emerging from a period of national disillusionment with a game whose primary selling point was innocent, nostalgic escapism. For better or worse, the face of the previous era is Barry Bonds. We may never again see a five-year run like Bonds’s 2000 through 2004, when he set the single-season home run record, won four straight MVP awards, and posted a 241 OPS+. From 2000 to 2007, Bonds posted a .517 on-base percentage, which means that over, essentially, seven full seasons (he missed almost all of 2005 with a knee injury) Bonds reached base more often than not. Ted Williams put together a seven-season run of a .500 OBP from 1941 to 1950, with three seasons lost to military service, and Babe Ruth had a six-season run from 1919 to 1924. No one else has ever come close.

But Bonds, in addition to being a drug cheat with a reputation for being less than media-friendly, stood trial on charges of perjury and obstruction of justice, and during his first divorce, Bonds’s ex-wife accused him of beating her on multiple occasions. There was a time when fans and media would have ignored transgressions like Bonds’s, but by the mid-2000s, they turned him into a pariah. Even beloved players of the time — Mark McGwire and Sammy Sosa in particular — sit in disgraced retirement today.

Trout is the best player among the post–Mitchell Report generation, but he might not be the most popular. Every so often, MLB releases a list of the best-selling player jerseys, and while Trout is usually in the top five or 10, he’s never led the list. Griffey had his detractors, but he looked like a movie star, moved like a ballerina, and was intensely brand-conscious. Trout looks like a thumb, moves like a bison, and is intensely not brand-conscious.

Normally, playing in Los Angeles would help Trout’s star, but three factors work against him. First, baseball is a local sport; fans can sit down and watch their favorite team six days a week, so there’s no national-event TV like Monday Night Football (there is a Sunday Night Baseball, but it’s not the same), and therefore no reason for anyone but the diehards to watch the whole league. Second, the Angels, name notwithstanding, play in Anaheim, and the Dodgers own Los Angeles. Trout is on a middle-of-the-pack team that plays its home games at 10 p.m. Eastern — he might as well play in Fresno for all the good the “Los Angeles Angels” moniker does him.

Third, and you can see this in the jersey sales rankings, the game’s biggest stars tend to play on teams that make memorable runs in the postseason, the only time the entire baseball world is watching. For example, Madison Bumgarner’s jersey was the sales leader after the 2014 playoffs. The best baseball player just can’t move the needle on his own the way the best basketball player can, and the Angels have wasted Trout to a staggering degree. They’ve made the playoffs only once in the past five years, and even then they bowed out without winning a game, depriving Trout of the national showcase that playing deep into October could have provided.

We need to start preparing ourselves for the possibility that Trout will end up as the best baseball player ever.

We need to start preparing ourselves for the possibility that Trout will end up as the best baseball player ever.

Since arriving in the majors, Trout has played five full seasons, and he’s won five Silver Slugger awards and made five All-Star teams. He’s led the American League in WAR five times, and finished no worse than second in AL MVP voting, including two wins. Since 1901, nobody except Williams has produced more WAR than Trout in his first six seasons, though Williams played an extra 81 games, and five of those seasons were pre-integration. Trout has the sixth-highest OPS+ (minimum 2,500 plate appearances) for a player in his first six years, though everyone ahead of him except Ty Cobb was older and played in a less valuable corner position. Trout has two 10-win seasons, a feat only five players (Trout, Bonds, and three Hall of Famers) have ever achieved. At his current pace, Trout will close in on 60 career WAR — the modern sabermetric floor for a Hall of Fame career — in early 2018, when he’s 26 years old, and with less than seven years of service time. He’ll have Hall of Fame numbers three years before he’s played long enough to be eligible for the Hall of Fame.

As a rookie, Trout hit .326/.399/.564 in 139 games with 30 home runs and a league-leading 49 stolen bases. But he lost a contentious MVP race to Tigers first baseman Miguel Cabrera, who was roughly Trout’s equal as a hitter but vastly inferior in all other aspects of the game. But Cabrera led the league in batting average, home runs, and RBI— the Triple Crown, a feat that hadn’t been accomplished since 1967 — and won 22 of 28 first-place votes as a result.

“Give me a place to stand and with a lever I will move the whole world,” said Archimedes, and that’s pretty much what the 2012 AL MVP race did to popular baseball analysis. Cabrera’s Triple Crown was a tipping point at which the back-of-the-baseball card stats stopped matching the eye test, and Trout has ascended to his exalted place in the public imagination despite having led the league in a Triple Crown category only once — an RBI title in 2014. Trout hasn’t necessarily changed the game, but he’s helped to change how we evaluate it.

Trout has a global superstar’s game, but while he seems like a very nice guy, he doesn’t have a global superstar’s comportment. You have to want to become Jordan, but Trout doesn’t want to be famous — he just wants people to like him. Take his choice of agent: Rather than signing with one of the bigger agencies, like the Boras Corp or Casey Close’s Excel Sports Management, Trout has stayed with Landis, a former minor leaguer whose roster of clients includes one, and only one, active big leaguer: Trout.

Trout has a global superstar’s game, but while he seems like a very nice guy, he doesn’t have a global superstar’s comportment. You have to want to become Jordan, but Trout doesn’t want to be famous — he just wants people to like him. Take his choice of agent: Rather than signing with one of the bigger agencies, like the Boras Corp or Casey Close’s Excel Sports Management, Trout has stayed with Landis, a former minor leaguer whose roster of clients includes one, and only one, active big leaguer: Trout.

Trout’s legend-building stories even play up his desire to play nice with others. In high school, the right-handed Trout won a home run derby hitting lefty — the kind of anecdote that makes him look superhuman. But Trout frames the story differently.

“I just wanted to have fun with my friends,” Trout said. “I didn’t want to show anybody up or do anything like that, but I thought it was pretty cool.”

For better or worse, drama sells. LeBron may get ripped for transgressions real and perceived, but when he does, it means he’s in the news. Jordan was fine with wearing the black hat when it suited him, and so is Harper. But Trout wants kids to look up to him.

“I have Little League and high school coaches come up to me all the time and tell me that they tell their kids, ‘This is how you do it. Period. In all aspects. This is your role model,’” Landis said.

In recent years, the phrase “playing the game the right way” has taken on a problematic second life, as it and phrases like it have been used to criticize players — specifically younger and/or black and Latino players — for showing too much emotion on the field or making headlines off it. Just in the past couple of weeks, Orioles GM Dan Duquette and Tigers second baseman Ian Kinsler have stepped in it. But since Puerto Rican stars Vic Power and Roberto Clemente got called hot dogs more than 50 years ago, perhaps it’d be more accurate to say that it’s only in recent years that we’ve started to care about how problematic those code words can be.

There’s no doubt some of the more culturally conservative fans, commentators, and people who work in baseball like Trout — a white American from a middle-class family who doesn’t rock the boat — because he’s not José Bautista, who in their minds represents threatening Latino emotionality, or even more controversial and outspoken white American players like Harper, who represent millennial narcissism.

Since they came up around the same time, Trout will always be compared to Harper, who landed on the cover of Sports Illustrated as a teenager, has a flashy haircut and beard, wears a lot of eye black, got a customized Mercedes-Benz at age 19, and when he gets ejected sometimes returns to the field after the game and curses out the umpire. If you love drama in baseball, you’ll love Harper. If you don’t, you might prefer a friendlier, more deferential superstar with a high-and-tight haircut, like Trout.

What separates Trout from those who might seek to utilize him as the poster boy for a serious, solemn, puritanical brand of baseball, though, is that Trout himself is neither particularly self-serious or solemn in his own conduct, nor puritanical about others’. He’s never publicly criticized Harper or anyone else for arguing a call or flipping his bat, and Trout leads the league in chatting with opposing infielders while he’s on base — to be fair, he’s on base a lot. With his big, ever-present grin, Trout often resembles nothing so much as a golden retriever given human form, and his attitude, at least as far as we know, is more ecumenical than Calvinist — he wants to play the game his way, but however you want to play the game is OK too.

Trout isn’t shy, and he’s not Steve Carlton giving the middle finger to the world. He just legitimately doesn’t seem to care one way or the other about his celebrity.

Trout isn’t shy, and he’s not Steve Carlton giving the middle finger to the world. He just legitimately doesn’t seem to care one way or the other about his celebrity.

Trout’s all over MLB’s advertising, he has a signature Nike cleat, and he’s appeared (thanks to a Hall of Fame marketing screwup by Jersey Mike’s Subs) in national commercials for Subway that, come to think of it, probably factor into his feelings on Hoagiefest. But while Trout has become synonymous with the Sweet Onion Chicken Teriyaki sandwich, for whatever that’s worth, Nike hasn’t capitalized on Trout. It hasn’t released a stand-alone Trout commercial. And although Steven Stamkos, Marlen Esparza, and Eric Weddle — Eric Weddle! — appeared in Nike’s cross-sport “Snow Day” ad in 2015, Trout didn’t, nor did any baseball player. The only entity that’s coming close to making the most of Trout as a promotional icon is MLB itself.

It’s easy to wonder why Trout would shrug at the opportunity to become baseball’s Jordan, but consider it from the other perspective: What does Trout risk by attempting to make that leap? And what does he stand to gain?

To become that kind of star, you have to become a brand, like LeBron, Griffey, Ronaldo, Tiger Woods, and Roger Federer did. And doing that is polarizing. Whether or not we should, as a society we don’t like people who tell us how great they are all the time. Self-promotion can come off as arrogant or tacky even if you do everything right. And one side effect of doing commercials and putting yourself on TV, or in the news, is that people get tired of you. Jordan, in addition to playing in the NBA Finals six times, did commercials for his own Nike brand, McDonald’s, Hanes, and Gatorade, and he released his own movie. It’s hard to imagine one guy being on our screens that much in 2017 without everyone hating him.

If Trout wants to be rich, he’s in Year 3 of a six-year, $144.5 million contract that, even after taxes, agent’s fees, and other expenses, will still put his great-grandchildren through college. When he hits free agency at age 29, he’ll probably ring the bell for another half billion. He’s on TV every night and has his own shoe, so he’s plenty famous already.

Trout wants other things, too, and his current level of fame grants them. A keen amateur meteorologist, he gets to go on the Weather Channel with Jim Cantore. He wants to root for the Philadelphia Eagles. The longest answer he gave me, by far, was about wide receiver Alshon Jeffery, who signed with the Eagles the day before I talked to Trout.

“Obviously last year we were banged up a little bit. Now they have some guys Carson [Wentz] can throw the ball to,” Trout said. “It put a lot of pressure on the young guys last year; [Nelson] Agholor and [Jordan] Matthews, put on a full workload. I knew how they felt, you know, coming into the league and being a professional. It just takes time. With Alshon and Torrey Smith coming in, it’s going to help them a lot.”

Trout’s exactly the kind of Eagles fan you’d expect a celebrity who grew up eating “begels” and washing them down with “wooder” to become. He referred to quarterback Carson Wentz by his first name because the two are hunting buddies. Last Christmas he gave every Eagle who wears Nikes a pair of his signature shoe, in white and midnight green, along with a charmingly low-tech card. He’s already living the dream.

It’d be great for baseball if a Trout billboard popped up once every mile of highway nationwide, if he cultivated rivalries, if his public persona weren’t as bland as the chicken noodle soup he favors, but that’s not what Trout wants.

While he gets along with everyone, the only person he has to answer to is himself.