Fans at the World Series in 1916. A quarter century earlier, Ella Black opened doors for baseball-loving women everywhere. (Photo: Library of Congress/LC-DIG-ggbain-22957)

On May 21, 1890, as she did on most spring days, Ella Black put on a hat, grabbed her press credentials, and headed out to the ballpark to do her job. That day, she was in New York, ready to watch the Pittsburgh Alleghenys face off against the Brooklyn Bridegrooms at Washington Park. When she reached the gate, she opened her pocketbook, pulled out her press card, and handed it to the ticket-taker.

The surprised man took her identification. He looked at her, read the name more closely, and then looked up again. “Well, well,” he said. “I’ve heard of you often, but I always thought you were a man. But you really are a woman!”

Ella Black got that a lot. As the world’s first nationally circulated female baseball writer, she was privy to plenty of double takes, obstacles, and confused men. Despite this, throughout 1890, she penned dozens of articles for Sporting Life, proving that a self-described “petticoated enthusiast” could chase stories and swap stats with the best of them. She covered bullpen politics, gave a voice to female fan culture, and sparred with male readers—and then, as suddenly a home run over the back fence, she disappeared. A century later, baseball historians are still trying to figure out exactly who she was.

The Brooklyn Bridegrooms in 1889, a year before Black saw them play. (Photo: WikiCommons/Public Domain)

In 1890, American baseball was going through a bit of an identity crisis. Over the 14 years of its existence, the National League had slowly consolidated much of the teams’ financial and decision-making power away from the athletes. Players couldn’t negotiate their own contacts, and they could be sold to another team on a dime, or suffer pay cuts for carousing after games. Dissatisfied with this, a group of ballplayers decided to split off into their own, unionized league, known as the Players’ League. Suddenly, many cities had two different teams, battling it out on the field and behind the scenes. Fans had to choose sides: Cleveland Spiders or Cleveland Infants? Boston Beaneaters or Boston Reds?

Black, who was from Pittsburgh, preferred the local Players’ League team, the Burghers, to the National League’s Alleghenys. As a member of a small women’s baseball fanclub, the Young Ladies of the Diamond, she saw the various ways each team drew in female fans, and watched how the women in turn influenced each team’s financial and competitive success.

She offered this insight up to Sporting Life in the form of a letter, published on March 5th, 1890, under the heading “A WOMAN’S VIEW.” “A Novelty in Base Ball Literature—The Base Ball Situation Considered and Commented Upon From A Female Standpoint,” the subhead explained further, before giving Black ten good column inches.

The front page of The Sporting Life the day of Black’s first publication. (Screenshot: LA84 Foundation/Public Domain)

Despite the enthusiasm of the Young Ladies of the Diamond, women baseball fans were uncommon—the sport, with its spitting and roughhousing and swearing at umps, was considered unfit for ladies. Women writers were also rare, and those who showed up in newspapers were often relegated to the “women’s pages,” dedicated to society balls, food, and fashion.

“As a woman writing journalism and also as a woman writing baseball, Black was doubly out of bounds,” says Scott Peterson, the author of Reporting Baseball’s Sensational Season of 1890. “At first, I think the editor of the Sporting Life published her letter as something of a lark.”

But Black wasn’t in it for a lark at all. “When she kept sending letters, and these reports had interesting and insightful information in them, they kept publishing them,” says Peterson. Eventually, the paper’s editor sent her press credentials—not that they were much use. Many of the baseball news hubs—locker rooms, bullpens, taverns—were, either legally or socially, essentially off-limits to Black. Even that Brooklyn ticket-taker wouldn’t let her enter without first checking with a higher-up.

“I did not care to indulge in so much red tape,” Black wrote. “I put an end to the conference by purchasing a ticket and feeling very independent as I walked in and took my seat.”

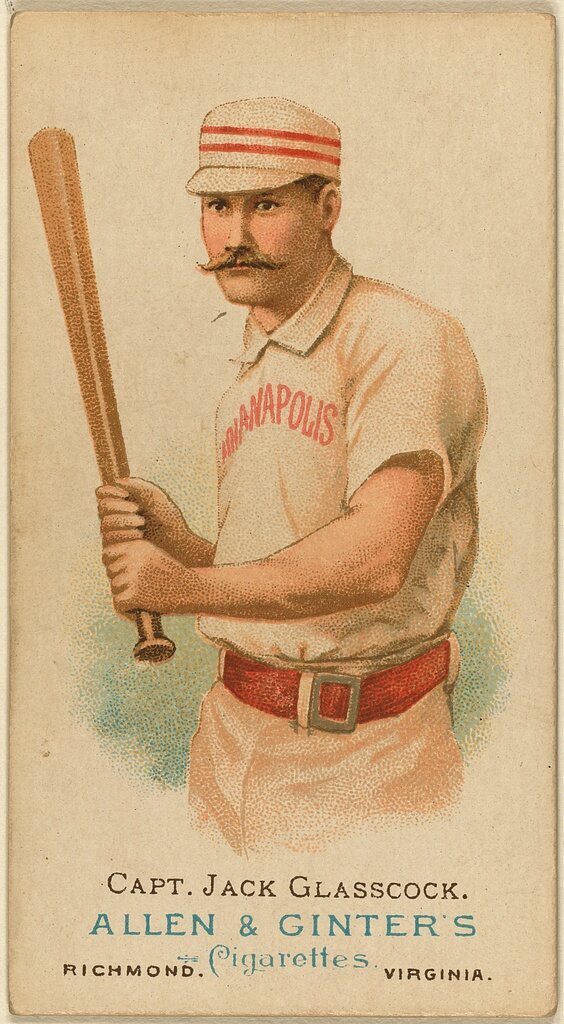

Jack Glasscock, notorious blackguard, during his Indianapolis Hoosier days. (Image: Library of Congress/LC-DIG-bbc-0004f)

This lack of access inspired great creativity. Black eavesdropped on officials on trolley cars and outside taverns (they spoke more freely around her, she said, because she was “only a woman“). She spied on new recruits with opera glasses. She developed her own unique beat, intertwining female fan culture with the two leagues’ growing rivalry. She revealed female fan favorites—women loved “fine-looking and shapely” catcher Fred Carroll, she wrote, and clapped so hard for first baseman Jake Beckley that the buttons came flying off their gloves.

On the other end of the spectrum, her whole club would be boycotting games featuring New York shortstop Jack Glasscock, she reported, because he tended to “swear and act like a blackguard.” During the coverage of the labor dispute, Black was one of the more objective voices, says Peterson: “She would be critical of both leagues if she thought they deserved the criticism.”

She also had a more overarching focus: she wanted to prove women could write about baseball. When nonbelievers pitched doubts at her, she swung true. “Mr. Editor, are you right sure that “Ella Black” is not the nom de plume of some gentleman correspondent?” wrote Joe Pritchard, a baseball reporter from St. Louis. “The letters are too newsy for a lady to compose.” Black fired back: “I only wish that I had the privileges of a man, then I would give the St. Louisian an idea of how much superior to some men a woman could be.”

When others said it was suspicious that the Pittsburgh players didn’t know her, she reminded them of her situation. “Women writers would be a strange sight lounging around hotels and cigar stores,” she replied. “So long as I can write base ball and not make myself conspicuous, all right; when cannot do so I shall stop writing.” Eventually, people stopped questioning her identity and just nitpicked her reporting—a compliment, in its own way.

A woman named Elsie Tydings, first in line for World Series tickets in 1924. By that time, women were a larger presence in the stands. (Photo: Library of Congress/LC-USZ62-98702)

Black’s last column ran on November 22, 1890; in it, she discusses the impending dissolution of the Players’ League, deftly shuts down another critic (“I am not a prophetess”), and wonders who will play for Pittsburgh that coming year. After that, she essentially disappeared. Several historians, including Peterson, have tried to puzzle out who she was, where she came from, and where she went next, but all have come up short. Even “Ella Black” was likely a pseudonym.

“We know for sure that she was living in Pittsburgh in 1890,” says Foster, “But that’s all. She is a figure of mystery.”

Wherever Black went, she propped the door open on her way out. People wrote into The Sporting Life asking after her, and saying she “numbered among the brilliants.” By the 1920s, Foster says, there were over 30 female sportswriters in America. Although numbers have gone up since then, we still have a long way to go—a recent Associated Press report put the proportion of female sportswriters in major newsrooms at around 15 percent, and many face online harassment that Black couldn’t have even dreamed of.

Still, someone has to be the first—first to step over the red tape, first to answer to doubters, and to overhear news tips on trolley cars from people who say she’s ‘only a woman.’ And that was Ella Black—whoever she was.