Baseball Beards: The Civil War Comps – Hardball Times

“Gen. Evan Gattis” has a nice ring to it. (via Arturo Pardavila III)

It isn’t that I’m oblivious to modern trends. Sometimes I turn a blind, or just a blurry, eye to them, waiting for them to fizzle out. I had been doing that with the proliferation of beards in baseball for the last few years. This October, though, binge-watching the playoffs so I could do some semi-informative moonlighting over at FanGraphs, it became something I could no longer ignore.

Beards are big. As a trend, and often as an actual collection of hair on the chin and jawline. It’s gone far past Brian Wilson doing his gonzo closer thing and become effectively the norm in baseball. Beards haven’t been this big in America for over a century, back to the era beginning with the Civil War.

That observation might be influenced by personal experience. My annual baseball tour, recounted on this site in varying thoroughness the previous two years, took a side trip this year to Gettysburg. (And no, not because General Abner Doubleday fought there.) That may have planted the seed of the distinctive beards of Civil War generals in my mind, and with the proper gardening in October, it sprouted.

This article could have been a quiz: baseball player or Civil War general? However, this would have required Photoshop skills in degrading modern photographs to the quality of the mid-19th century that I do not possess, and I wasn’t patient enough to acquire them for one silly piece of baseball writing. Instead, I’ll pretend to be a little more analytical, making tonsorial matches between today’s ballplayers and the long-past managers of a much bigger contest.

Most of my selected players hail from this year’s playoff teams, for the practical reason that they were right in front of me for weeks at a time, and I was already taking notes.

Lower Ranks

It’s the biggest, bushiest beards that draw the most attention, but even in current baseball those aren’t the most common ones we see. Some beards are kept under strict control or just haven’t had time to grow as thickly from young chins as their owners might desire.

With the close attention many Civil War generals gave their whiskers, that means some ballplayers just don’t have a decent match. I have to relegate them to the ranks of the foot soldiers, which is only fitting. In any army there are generals and there are enlisted men. The following fellows will have to be content as grunts, perhaps with hopes of coming up through the army ranks.

But which army? Choosing between the North and the South is a matter of personal aesthetics, perhaps one that won’t translate well to my readers. But what the hey, I’m trying it.

For instance, there is something about the more gingery beards that suggests “South” to me: young dirt farmers with hair bleached by a hot southern sun, signing up to fight them Yankees. I’d prefer something a little scruffier, looking like they’d been marching hard on short rations for a while, but I’ve got to pick, so Wade Davis and Ben Zobrist are out of royal blue and into gray.

These kids, Kevin Pillar and Kyle Schwarber, I would instead put in the Union Army. Granted, Schwarber’s look suggests “Union soldier” less than “often drunk frat boy.” However, his round, well-fed face fits the better-supplied Northern ranks, and that tuft carries a hint of Pennsylvania Dutch farmer with it.  He needs to be careful, though. Grow it out too low, and he’ll end up resembling Confederate President Jefferson Davis.

He needs to be careful, though. Grow it out too low, and he’ll end up resembling Confederate President Jefferson Davis.

I must admit, imagining Davis as a drunken frat brother makes my brain lock up like a 486 processor trying to play Fallout 4.

A few players have too little of a beard to fit anywhere. Josh Donaldson manages that trick.  Nobody in the Civil War would have styled a beard like that, even when first growing it out to a greater length. They would have started off scruffy, or just kept clean-shaven. Our reigning American League MVP has no place in the War Between the States. Given that he’s playing for the lone Canadian team, this actually works out.

Nobody in the Civil War would have styled a beard like that, even when first growing it out to a greater length. They would have started off scruffy, or just kept clean-shaven. Our reigning American League MVP has no place in the War Between the States. Given that he’s playing for the lone Canadian team, this actually works out.

Generals

Enough of the privates, sergeants, and non-combatants. Let’s get to those generals. The best route to them is through the top echelon of baseball players. MVP Donaldson was no help to us, but the new Cy Young Award winners are much better.

We can start off with perhaps the most distinctive beard in the majors today, that of Dallas Keuchel. This beard alone gets people thumbing through indices of Civil War generals, and there are plenty that can offer a reasonable match. Lots of those generals went long and thick as Keuchel does, threatening to produce a logjam over which bears the nearest resemblance.

To break the impasse, I looked at the particular quality of Keuchel’s whiskers. They’re individually distinct, not blending into a seamless whole, and they’re rather scraggly, not groomed smooth and straight. Also, Keuchel’s mustache is not exactly staunch, a matter we’ll examine more closely later. There’s one man who matches Keuchel’s qualities, even though his own beard was a good twice as long: Union general John Schofield.

Schofield wasn’t exactly a paragon. He had clashes with superiors, was suspected of Confederate sympathies, and wasn’t all that effective on the battlefield. During a later stint as Secretary of War, he would recommend himself for the Congressional Medal of Honor on nebulous grounds, and eventually he received it. Unless Keuchel can find a way to vote himself his next Cy Young Award, he’s better off seeking someone else as a model.

Which general? The shape and consistency match one in particular, even if Arrieta manages to be thicker by the ears. My choice is Thomas Jackson.

Originally scouted for his defense (winning the nickname “Stonewall” in the first major battle of the war), Jackson was a five-tool general. His 80-grade speed led his soldiers to be nicknamed “foot cavalry,” and his fast strikes out of nowhere won more than one battle for the Confederacy. His career was cut short in its prime. Shot in his non-throwing arm in May of 1863, Jackson contracted pneumonia while recuperating and died. His replacements off the bench would let the South down terribly at Gettysburg.

And don’t worry, I won’t use baseball terminology to describe any more generals. I just had to get it out of my system that one time.

I mentioned jutting beards, and an outstanding example of this is Evan Gattis. Part of this may come from a strong chin, but the rest is pure hair. Lucas Duda exhibits a similar style, with a little more underhang. Seeing the two face each other above is like watching two old-fashioned trains, complete with cow-catchers, chugging toward each other. It’s too bad such strong beards have such an iffy comp.

Fitz John Porter isn’t one of the more famous Union generals, because he wasn’t around all that long. His overly passive role at Second Manassas in August of 1862 helped lead to the Northern army’s defeat and got him relieved and court-martialed. The fault was more commanding general John Pope’s for some bad orders, but Pope needed a scapegoat—and the proper candidate, the merely mustached George McClellan, was too big a cheese for the role. Porter would be exonerated nearly two decades later, but his reputation never truly recovered.

If this portends anything for Gattis and Duda, they had better be sure to get all their signs right. Otherwise they could find themselves hung out to dry one day.

If you want a really ominous comparison, though, we can go with Josh Hamilton. A fresh episode of cocaine use, plus a Houdiniesque avoidance of league punishment, left him so poisoned with the Angels that they paid Texas well to take him away. Hamilton soon was sporting the beard to the right, apparently trying to look like a new villain on The Walking Dead.

His beard is approaching that of several Southerners, like John Gordon and Patrick Cleburne, though it really needs added length at the chin. Something in Hamilton’s expression, though, moves me to waive the length and link him with Nathan Bedford Forrest. When Forrest was good, he was MVP good, one of the Confederacy’s outstanding cavalry leaders. When Forrest was bad…well, after the war he was an early leader in the original Ku Klux Klan.

Consider that a last warning, Josh. But start inward, and work your way out to the beard.

There are other instances when the resemblance goes beyond the beard. I was struck by how similar Blue Jays knuckleballer R.A. Dickey‘s appearance is to Union general John Fremont. The resemblance is most remarkable around the eyes, but the beards are close enough also to make it a little eerie.

Fremont had been the Republican Party’s first Presidential candidate, in 1856. (They’d do better next time.) His agitation and obvious opposition to the rebellion got him a political appointment as a general. He was worse as a general than as a candidate, producing political messes for Lincoln to clean up and getting pushed around by Stonewall Jackson. Reassigned to fight under someone he outranked, he resigned in outrage and never served again—which might have been the aim.

Such political appointments were remarkably common in the Civil War. For instance, John Breckinridge, vice-President to James Buchanan and one of Lincoln’s opponents in the 1860 election, ended up a general in the Confederate Army. But he was clean-shaven, so the heck with him.

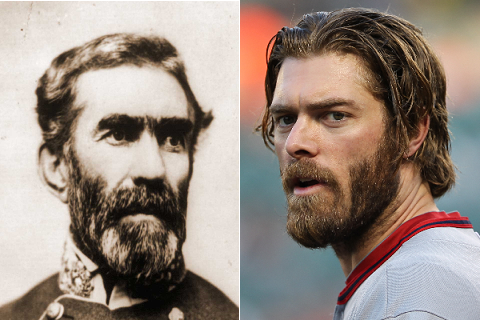

Dickey isn’t the only player with a 19th-century doppelganger. Take a look at Jayson Werth, as he was four years and significant beard growth ago, compared to confederate general Braxton Bragg.

Bragg cut a frightful figure, and I don’t just mean those eyebrows. A martinet who shunted blame for lost battles onto his subordinates, Bragg may have been the worst general of the Civil War. His friendship with Jefferson Davis kept him in the field long beyond the time anyone else would have sacked him. Plus the eyebrows. Egad, those eyebrows.

Werth wisely abandoned this look as fast as his follicles (which showed laudable restraint over the eyes) allowed. He did it mainly with his mane, growing it long and stringy, though his beard is also fuller these days. Werth probably falls back into the enlisted ranks with his current ‘do, but that may be for the best, as his earlier resemblance was nothing to Bragg about.

(And hopefully the mirror shades aren’t hiding his eyebrows getting adventurous.)

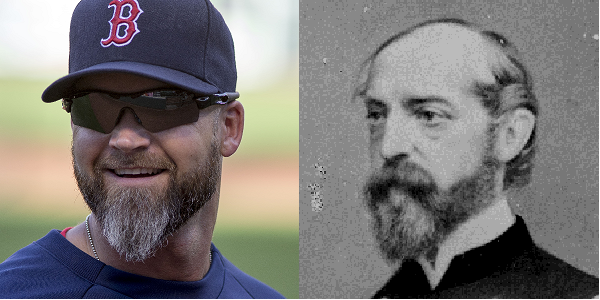

Getting back on track, Mike Napoli rocks a pretty good beard. You see it here in the victory parade after his 2013 Boston Red Sox, a team chock-a-block with big beards, won the whole shebang. The beard’s waviness eludes perfect matches in the military ranks: those fellows were more straightforward. Going by shape and volume, though, I will link it up to Rebel general A.P. Hill.

Ambrose Powell Hill was one of Lee’s most trusted lieutenants. He regularly went into battle wearing a red shirt, possibly to make it less conspicuous to his men should he be shot in action. Napoli, with time on the Red Sox and Rangers, can identify. Hopefully he would identify less with the mysterious illness that sometimes kept Hill out of battle or made him a less effective general while fighting: reputedly it was a venereal disease that kept flaring up.

David Ross, Napoli’s teammate on those champion 2013 Sox, has his own distinctive beard, with a spade shape at the chin accentuated by having gone gray ahead of its neighbors. There’s a surprisingly good match for Ross in George Gordon Meade, the man who beat Robert E. Lee’s Confederates (including Hill) at Gettysburg. Meade wasn’t a brilliant general, but if he played tortoise to Lee’s hare, we know how that match turned out.

Even the coloring at Meade’s chin parallels Ross’s whiskers. Granted, there are two significant differences between the men, one being Meade’s baggy eyes. Hmm, perhaps that explains David’s sunglasses? The other is the heavy mustache of Meade, which Ross does not match, and frankly isn’t trying to.

This highlights perhaps the greatest difference separating the ballplayers from the generals: the weakness of modern mustaches. Some are skimpy afterthoughts; some are neatly, closely trimmed. Few have the strength, the fullness, the luxuriant volume that many in the Civil War could boast.

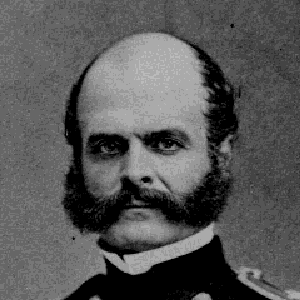

Today’s players can emulate the chin whiskers of Winfield Scott Hancock, as Yovani Gallardo manages to do. They simply don’t compete with Hancock’s admirable mustache, and his is a relatively modest example. What upper lip in baseball today could you imagine producing something like this?

That is, of course, Ambrose Burnside, whose mustache flows smoothly into the rivers of whiskers that would come to be named after him: sideburns. One could possibly imagine an 1880s player sporting this look, but today it is unthinkable.

What has happened to turn ballplayers’ mustaches into such pale shadows? My theory is that it is a practical decision. Mustaches today are kept modest because they otherwise would interfere too much with spitting. Tobacco juice, sunflower seed detritus, stray bubble gum, and just plain spittle could too easily lodge there, becoming an eyesore. (Theoretically, the players could stop spitting, which is about as likely as their ceasing to breathe, or adjusting their cups.)

But this didn’t concern players in the 1970s or even later, when folks like Rollie Fingers, Sparky Lyle, and Al Hrabosky were making an art of mustache grooming. What’s changed since then is the advent of high-definition TV. Flaws that disappeared on fuzzier televisions are now sharp and clear, and any player with something stuck in his ‘stache is a potential figure of ridicule on a myriad of sports highlight shows. That powerful evolutionary factor keeps today’s mustaches smaller.

The Top

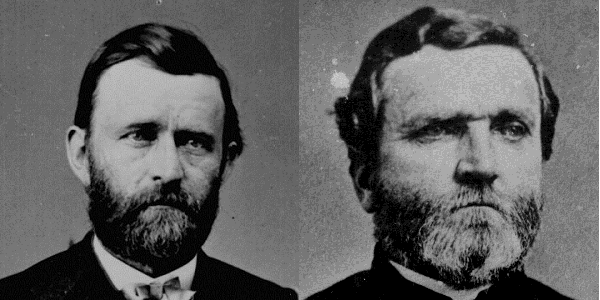

I started this match game by playing off big players, but it’s now time to use big generals as my starting point. Few were bigger than Ulysses S. Grant, who rose to command of all the Union armies by 1864. And there are a couple of reasonable matches for him.

Pitchers Brian Schlitter (Cubs, left) and Luke Hochevar (Royals, but shown with the Triple-A Omaha Storm Chasers) have the right stuff, if you exclude the long hair. Well-rounded beards up front, tapering to thinner whiskers at the sideburns, match Grant nicely. But they cannot come close to the match for Grant pulled off by another Civil War general.

Left is Grant; right is General George Thomas. Thomas rose up the ranks in Grant’s shadow but was a very fine general himself. His staunch defensive work made Stone’s River a victory and saved Chickamauga from becoming a rout. Late in the war, the Rock of Chickamauga proved his offensive chops by destroying John Hood’s Army of Tennessee at the Battle of Nashville.

Had I not labeled them a paragraph ago, you might not be able to tell Grant and Thomas apart, at least without a 50-dollar bill on hand, except that President Grant on the money has gray in his beard that matches Thomas’s during the war. No wonder 20s and 100s are more popular: Andy and Ben aren’t trying to trick anybody.

But don’t start going gray, big guy. That would just confuse things.

The most famous general of the war, on either side, was of course Robert E. Lee. Dubbed “The Marble Man” by a mildly besotted biographer, Lee took command of an army reeling on the edge of doom and led it to an amazing series of victories. In doing so, he won from his soldiers and his country a loyalty and reverence that has long outlived both.

There is no player who can match Lee’s appearance, mainly due to that marble-white beard. That doesn’t mean nobody in baseball can. Joe Maddon isn’t quite there, with his sideburn areas still clean and a bit too much color in the beard he does have. But he’s getting close, and his resemblance to General Lee goes beyond the physical.

(Forgive my using a YouTube video for Maddon. All the free photos were from his beardless Tampa Bay days.)

Maddon took over perhaps baseball’s ultimate lost cause, the Tampa Bay Devil Rays, in 2007. Within two years, he won the AL pennant with them. In doing so, and in the years that followed, he won a great amount of loyalty from his players and respect across the game. Then he went to baseball’s other great lost cause, the Chicago Cubs.

Perhaps it was a subliminal identification that led Maddon to start growing his current beard. It would be apt. Maddon doesn’t even need to win the war altogether with Chicago. If he gets the Cubs a pennant, the cult of Lee that has endured a century and a half will have a match in the cult of Maddon.

As long as I’m covering the highest generals, I may as well do something with their commanders-in-chief. I already threatened Jefferson Davis with a linkage to Kyle Schwarber, so I’ll leave him alone, but Abraham Lincoln doesn’t have that excuse.

Putting his picture here is almost superfluous, as his may be the most familiar face in American history. It will serve, though, to make comparison easier, seeing the beard following the deep hollows of his cheeks, plus the clean upper lip.

One could argue that Royals hurler Kelvin Herrera presents something of a match. One could also argue Herrera looks like a fourth-rate wax museum’s version of Lincoln, if that museum had a fire that partly melted the figure. The square notch below his bottom lip doesn’t help, either.

There is a much better match, if one manages not to notice one particular flaw. The match is Clayton Kershaw.

The dark beard follows the full circumference of the face, including his sunken cheeks. It adds lankiness to a frame that, just like Lincoln’s, stood 6-foot-4. Even Kershaw’s athleticism matches well. Lincoln is anecdotally known to have been remarkably strong in the arms, a state familiar to the consensus best pitcher in baseball.

The flaw is Kershaw’s thin mustache, where Lincoln had none. Here the weakness of modern mustaches plays in Kershaw’s favor: it isn’t too hard to miss the mustache entirely at a distance. Plus, if he ever decides to shave it (and trim the long hair), he could have a second career as a Lincoln impersonator. That doesn’t pay as well as his current job, but it’s good to have a fallback.

There’s still one player I would like to find a match in the ranks of the generals. He’s the man who ignited the current wave of beards in the majors, that gonzo closer I mentioned right at the start: Brain Wilson.

I’d like to find him a match, but it cannot be done. Nothing even in the grooming-obsessed ranks of the Civil War can come close to that awesome jet-black artifice produced by Wilson. There can be no comparison. He is unique.

A pity, really, nobody in the war grew a beard like that. It could probably stop a bullet.

References and Resources

- Special thanks to John Lachacz, whose classroom use of beards to tell Civil War generals apart for his students was part of the inspiration for this work.

- All photographs come from Creative Commons sources, cropped and resized to fit on the page. Sources for the photographs are: Arturo Pardavila III (Wade Davis, Zobrist, schwarber, Donaldson, Keuchel, Arrieta, Gattis, Herrera, Kershaw), Keith Allison (Pillar, Hamilton, Dickey, Werth, Ross, Fielder), slgckgc (Duda), Bob P.B. (Napoli), Mike LaChance (Gallardo), John (Schlitter), Minda Haas (Hochevar), Robert D. Bruce (Wilson), Marion Doss (Jefferson Davis, Hill, Meade, Hancock, Burnside, Grant, Thomas, Lee), Snapshots of the Past (Schofield, Porter, Bragg), Cliff (Jackson), TradingCardsNPS (Forrest), Wystan (Fremont), Believe Creative (Lincoln), and Frank Boston (the $50 bill).

- Thomas R. Flagel’s The History Buff’s Guide to the Civil War (electronic edition) provided historical data and helped me insult some of the worse generals.

- Stephen W. Sears’ Controversies and Commanders (electronic edition) said far more about the Porter affair than I could possibly fit into a baseball article.

- Wikipedia helped flesh out the historical facts.