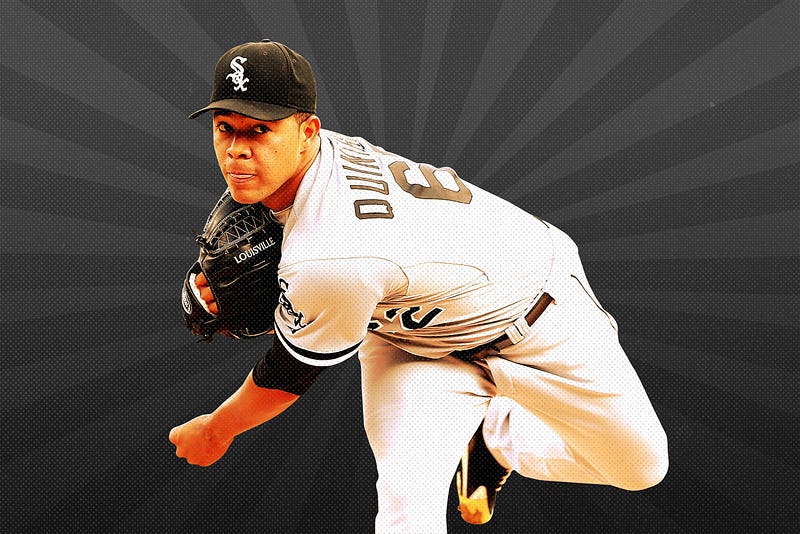

Elias Stein/Getty – The Ringer (blog)

Can Baseball’s Most Anonymous Ace Get Some Love?

And maybe some more wins?

José Quintana’s jersey isn’t available for purchase in the MLB.com store.

Nothing better encapsulates the baseball world’s underappreciation of its most anonymous ace. Well, other than this: The body text of Quintana’s Wikipedia page hasn’t been updated since 2014.

The Colombian pitcher was never a top prospect, made this year’s All-Star game only as a third-choice injury replacement, and is not even the White Sox’s most recognizable 27-year-old southpaw. The combination of his nondescript pitching style and a historically aberrant lack of wins has made the former minor league free agent — the best such signing in years — the rarest of 21st-century phenomena: a star-caliber player who isn’t recognized as such.

Quintana, quietly, has become one of the best pitchers in baseball. Since the start of last July, he has been the AL’s most valuable pitcher by FanGraphs WAR. In 2016, he ranks fifth in the AL in ERA, sixth in innings pitched, and third in fielding- and park-adjusted run prevention. He is, and has been, pitching like an ace.

His relative obscurity stems first from an approach based in efficiency rather than an overpowering arsenal. Unlike other top pitchers, his strikeout totals are nothing special. He can’t sling a 100-mph slider over the outside corner or turn batters’ knees to mush with a 12–6 curve. He succeeds more due to what doesn’t happen while he’s on the mound than due to what does; he avoids surrendering home runs and walks. Quintana is the minimalistic ace, his low ERA emerging from the white space between the digits in a daily box score.

Pitch-tracking site Brooks Baseball says his curveball has “little depth” and, until this past week, also called it “a prototypical pitch with few remarkable qualities.” The same might be said of his other offerings, which include a four-seam fastball that doesn’t much move and a sinker that doesn’t much sink.

Except that unremarkable curveball has been one of the most effective in the game for three years now, and his fastball has reached Clayton Kershaw–Stephen Strasburg levels of unhittability this season.

Quintana’s is a subtle sort of success: a prospective rally fizzled out before it does harm, an extra few popups nestled safely in an infielder’s glove. You take your eyes off the screen, and another scoreless inning passes by.

But those scoreless innings have added up to a whole lot of no-decisions, so Quintana’s greatness passes by unnoticed as well. While teammate Chris Sale (14–3) leads the AL in wins, Quintana scuffles behind with a 7–8 record. This disparity comes on the heels of three consecutive seasons in which Quintana pitched 200 innings, posted above-average numbers, and won only nine games each year.

After Quintana was initially left off this year’s All-Star roster, a number of White Sox suggested that his subpar record was the culprit behind his snubbing.

“If you compare him and I and put our numbers back to back, you would probably have a hard time figuring out who is who, honestly — other than wins and losses,” Sale told CSN Chicago. “Those are things you really can’t control.”

Quintana would know, because over his years on the South Side, he’s tried handshakes, prayer, and pregame shouting rituals to wrest some semblance of superstitious control over his fate — everything short of tearing up his contract and deserting his team to join the star-studded lineup across town.

Those efforts have been all for naught. He ranks last among AL pitchers in run support in 2016, after ranking in the bottom-seven in the league in each of his previous full seasons. It’s not a problem with the White Sox overall, either: Chicago has scored around three runs per game in Quintana’s starts, compared to more than six per game in Sale’s.

Receiving any semblance of support has become so unexpected that after the White Sox won 4–1 in early July, giving Quintana his first win in nearly two months, the lefty offered a surprised “wow” when asked about his team scoring four.

Quintana tends to miss out on wins no matter how well he pitches. He’s earned a win in fewer than half of his career starts in which he hasn’t allowed an earned run. Over that same span, the average pitcher has won more than 75 percent of those games.

At the other extreme, his unluckiness manifests in similarly anomalous fashion: In his most recent start, he won when allowing three earned runs or more for the first time since before the 2013 All-Star break. Since then, 119 pitchers have thrown more than 300 innings; per Baseball-Reference’s Play Index, Quintana became the 118th on that list to collect such a win.

All this discussion of wins might seem archaic, given the widespread success of Brian Kenny’s “Kill the Win” campaign. They are no longer the statistic of choice to judge pitcher value, and, save for a historic pursuit — people will care if Strasburg makes a real run at 20–0 in the next few months — the oft-misleading statistic no longer dominates baseball discourse.

Wins still matter at the extremes, though. It’s still strange to see a top pitcher with single digits in the wins column, and Mike Mussina’s and Curt Schilling’s sub-300 career win totals are viewed in some circles as black marks on their Hall of Fame candidacies.

Wins also matter specifically to Quintana, whose outrageously team-friendly contract calls for a $10.5 million club option in 2020. That figure would increase to $14 million if he wins a Cy Young award in the interim or $13 million if he nabs a second- or third-place finish in the annual vote.

For a player who has earned less over the course of his MLB career than teammate James Shields has just this season, and for whom just $10.5 million would represent an annual high even as salaries around him skyrocket, those extra millions matter. And if history is any indication, Quintana will need more wins to receive sufficient Cy Young consideration. No starting pitcher has ever finished in the award’s top three with fewer than 12 wins, a seemingly accessible number that nonetheless would represent a 33 percent increase over Quintana’s career high.

A lack of recognition in the top line of the box score has already kept him mired in relative national anonymity, as unfair as that connection may be, but it’s not hard to imagine how significantly a jump up the wins leaderboard might boost both Quintana’s Q score and his bank account.

At the very least, it might finally land him a personalized jersey at the team store.