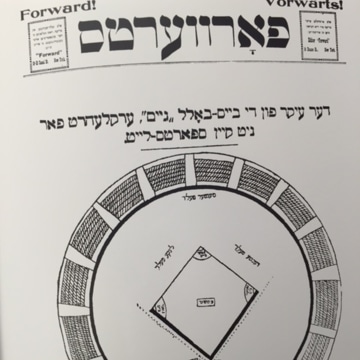

In August 1909, The Forward, a Yiddish-language daily newspaper for New York’s newly arrived Jewish immigrants, printed a front-page guide to the game of baseball, including a crudely drawn ballpark.

The feature, titled “The Fundamentals of the Base-Ball ‘Game’ Described for Non-Sports Fans,” may now seem quaint. But historians say it speaks to Eastern European Jews’ struggle to fit into American society, and how generations of them sought acceptance through baseball: understanding it, playing it, cheering it.

“Baseball is a meeting ground for all hyphenated Americans, be it African-Americans, Jewish-Americans, Latin-Americans,” said Rachel Lithgow, executive director of the American Jewish Historical Society in New York, which is hosting a traveling exhibition that charts the sport’s impact on Jews’ integration into American life — as well as its influence on other minority communities.

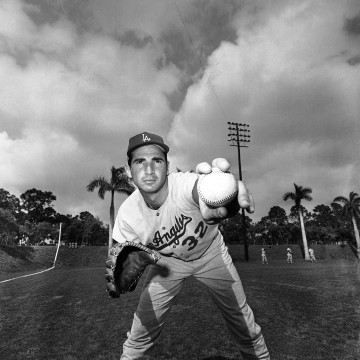

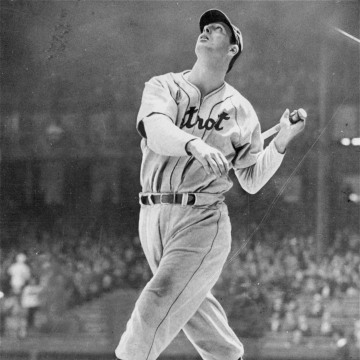

The exhibit, a pop-up version of one called “Chasing Dreams” that originated at Philadelphia’s National Museum of American Jewish History and is now at the Skirball Cultural Center Museum in Los Angeles, focuses on the early 20th century, when the arrival of millions of Jews coincided with the rise of the national pastime. It traces the link between baseball and social reform efforts to help Jews prove loyalty to their country. It celebrates the sport’s Jewish figures (including many early team owners and the composer of “Take Me Out to the Ballgame”) and superstars such as Hank Greenberg and Sandy Koufax. And it examines their continued impact on the sport.

“It’s more a celebration of the ways in which Jews in particular embraced the game and found their way into the American mainstream very quickly,” said Bob Kirschner, the Skirball’s director. “That followed in other vocations and areas of society as well.”

Baseball’s early history is dotted with anti-Semitism, primarily as a function of anti-immigration anxiety, and mostly directed toward owners and other off-field figures. The role of Jewish gamblers in the 1919 “Black Sox” scandal didn’t help. “Chasing Dreams” includes a quote from industrialist Henry Ford, who wrote the following year, “If fans wish to know the trouble with American baseball, they have it in three words — too much Jew.”

Jewish ballplayers faced discrimination too, but they were never banned outright from the game and, because of their skin color, were able to assimilate more easily than blacks, who didn’t break into the major leagues until Jackie Robinson’s debut with the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1947.

The first documented Jewish baseball star was Lipman Pike, a power-hitting utility fielder who played in the 1860s-’70s and hit six home runs in one game for the Philadelphia Athletics. The first modern Jewish star was Greenberg, who debuted with the Detroit Tigers in 1930 and gave up three of his prime years to serve in the Army during World War II. And the first Jewish hero was Koufax, who was not a practicing Jew but asserted his identity in the 1965 World Series, when he refused to pitch for the Dodgers on Yom Kippur.

For Jews, it was the kind of moment that you remember where you were when it happened, Kirschner said.

“To have Yom Kiuppur fall during the World Series was always a dilemma for me as a child, being in synagogue and wanting to listen to the game,” Kirschner said. “And here was Sandy Koufax saying, ‘You know what, I never claimed to be an observant Jew but this is a significant moment to claim pride in my ancestry.’ For Jews around the world, this was just a seismic moment.”

These days, now that at least 160 of Jewish players have reached the Major Leagues, according to Jewishbaseballnews.com, it’s no longer a big deal. The same could be said of Jews’ larger assimilation into American culture.

Rebecca Alpert, a Temple University religion professor and a baseball historian, said that baseball’s influence on Jewish life — and on immigrant life more broadly — has diminished as Jews have blended into American society and baseball relinquished its spot as the country’s dominant sport. “It’s just one dimension of who we are,” she said.

But there are still people who keep track of the number of Jewish players in the Major Leagues (fewer than 10 at last count), and argue over the Jewishness of players like Ryan Braun (who identifies as Jewish, but whose mother is not), a former Rookie of the Year and Most Valuable Player who served a 65-game suspension for using performance-enhancing drugs.

There is perhaps no better example of baseball’s role as an “agent of integration” than John Thorn.

His parents, Polish-born survivors of the Holocaust, had him while living in a refugee camp in West Germany and settled in New York when he was 2. He learned to read from baseball cards, which he says served as his passports to street corner life in the Bronx.

Thorn fell in love with the game, and discovered that, although he was a decent player, he excelled at collecting statistics and stories.

This was between the eras of the first two Jewish superstars: Greenberg, the Detroit Tiger slugger who retired in 1947, and Koufax, the pitcher who joined the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1955. But it coincided with the rise of Jackie Robinson, the Dodger who broke baseball’s color barrier in 1947. Thorn and countless other Jewish fans identified with Robinson as members of a marginalized group.

“All people who have been the wretched refuse of society identified with him,” Thorn said.

Thorn studied English in college and graduate school and began writing books on baseball. In 2011, he was named Major League Baseball’s official historian. He says he never felt more Jewish than when he got that job.

“People find it almost as astounding as I do that someone who was not born in America should be entrusted to explain baseball,” he said.

Those who examine the game’s history closely enough will not.

Chasing Dreams is at the Skirball Cultural Center in Los Angeles through Oct. 30 and at the American Jewish Historical Society in New York through July 31, then travels to the Detroit Historical Museum, the Sherwin Miller Museum of Jewish Art in Tulsa, Oklahoma, and the Skirball Museum in Cincinnati.