Four baseball icons share their stories of struggles at Negro Leagues museum event – CBSSports.com

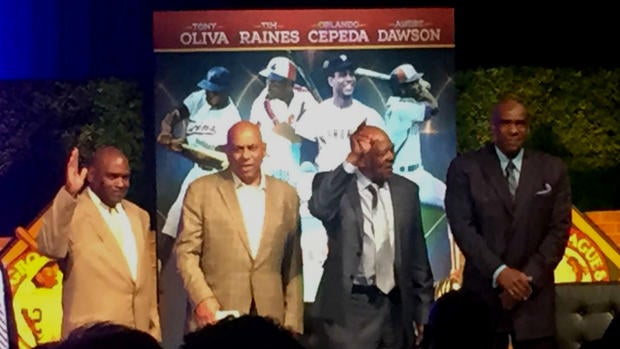

KANSAS CITY, Mo. — The crowd had gathered at the Gem Theater in Kansas City to watch four of the greatest players in baseball history talk about their careers. But for Andre Dawson, Orlando Cepeda, Tony Oliva and Tim Raines, Saturday night’s Hall of Game ceremony offered both a chance to be honored and to honor others.

“The players who came before us,” Raines said, “they paved the way for us.”

In its third year, the Hall of Game is the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum signature event, celebrating a new quartet of players each time. Each of the four shared words of wisdom about baseball’s past, and about the Negro Leagues mandate of employing top African-American players, at a time when Major League Baseball wouldn’t let them in.

Already an inductee into the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, Dawson spoke warmly about being honored in Kansas City as well. He praised all-time greats like Josh Gibson, the Negro Leagues catcher who’s universally regarded as one of the best players of all time in any league, someone who historians strongly believe would have dominated MLB too. But Dawson said the true impact of the Negro Leagues didn’t lie solely in those top-of-the-marquee names.

“How much would the major leagues have been if the great players in the Negro Leagues — all of them — got to play?” he said.

Bob Kendrick, the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum’s president, reflected on the biases faced by dark-skinned, Latin-born players during the same era, and even in the years following Jackie Robinson’s major-league debut in 1947. For Oliva, those biases showed up from day one.

Though he identified with his home country of Cuba and not his skin color per se, Oliva’s big-league debut in 1962 still came with plenty of prejudice. “Black is black,” he said of his treatment in that era. When Cuban-born Luis Tiant was honored at the Hall of Game gala last year, he spoke of being called the N-word upon his own big-league debut in 1964 … and not knowing what it even meant.

As for Cuban beginnings, Oliva shared an amazing story of his journey to the big leagues. A promising hitter, Oliva earned a tryout from the Minnesota Twins in April 1961. He failed to impress the club’s talent evaluators, setting up what would normally be a ticket home.

The problem was, he couldn’t go home at that time. A few days later, the Twins gave him a second chance, one which this time was enough to impress the team, earn Oliva a contract and launch a dazzling 15-year career in the majors. So what exactly happened that led to that second chance?

“The Bay of Pigs saved me!” Oliva said, bringing down the house.

Speaking last, Cepeda shared the evening’s most jarring story of racial persecution. At age 17, Cepeda started his professional career by playing in Kokomo, Indiana, of the Mississippi-Ohio Valley League. Cepeda thrived on the field during that 1955 season, batting a terrific .393/.433/.634. Off the field, the Puerto Rican slugger described a nightmarish existence.

Three decades earlier, Kokomo had hosted the largest Ku Klux Klan gathering in history, with more 200,000 Klan members and supporters attending. Cepeda described signs plastered all over town with messages like, “No blacks. No Mexicans. Dogs allowed.”

“That’s how I learned that with bitterness and negativity you can go nowhere,” Cepeda said.

The third annual Hall of Game increased the total money raised by the event since 2014 to more than $700,000. That’s a boon to the museum, Kendrick said, especially at a time when both sports museums and museums celebrating African-American culture are struggling.

Founded in 1990, the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum at 18th and Vine Streets in Kansas City consisted of one room barely big enough to hold a conference table at the start. Kansas City Monarchs legend Buck O’Neil was the driving force behind the museum, paying the rent out of his own pocket, and soliciting fellow former Negro Leaguers to do the same.

In 1997, the museum expanded, moving into a much larger space that includes a 10,000-square-foot gallery, as well as office space, and shared space with the American Jazz Museum. Setting up shop at 18th and Vine was, Kendrick said, a conscious and deliberate decision.

“There were other places with built-in traffic, better financial possibilities,” Kendrick said. “But this was never a self-serving proposition. Buck knew that this would spawn a revitalization in what had once been a proud African-American community. Had we not moved here, I don’t think we would have seen this kind of transformation in the district in the past 25 years.”

Housed in an enormous building and featuring giant room after giant room of artifacts and plaques, the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, New York, is considered by many to be the gold standard of baseball museums. But there’s something about the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum that can, in some ways, resonate even more.

Walk through the main doors and you’ll immediately come across the Field of Legends. A mock baseball diamond situated in a sprawling room, it features 10 life-size bronze sculptures of Negro Leagues greats, cast in their natural positions as if they’re playing a game.

Those include Gibson, the prodigious power hitter whose tape-measure homers have become almost mythical in stature over the years. Oscar Charleston, the highly decorated center fielder who batted .353 and slugged .576 during his Negro Leagues career, while also ranking as one of the best defensive players in the game. Satchel Paige, who combined dynamic pitching with unmatched showmanship to become a barnstorming legend who drew record crowds wherever he went. And my favorite, Cool Papa Bell, the fleet-footed outfielder who was so fast, his admirers would say he could flick off the light switch and be in bed before the room turned dark.

More than that, it’s an incredible learning experience, about both baseball and America. The museum aims to honor the legacy of the many great players who played in the various affiliated leagues, from the Cuban Giants taking the field as the first black professional team to the final days of the Negro American League in the 1950s.

My first visit in 1999 was almost overwhelming, given how much I learned about American history — from post-Civil War Reconstruction to the days leading up to the Civil Rights Act of 1964 — through the lens of the Negro Leagues. That the museum itself has helped revitalize one of the city’s oldest neighborhoods only adds to the appeal.

The next time you’re pondering a baseball road trip, go to Kansas City. Stuff your face with barbecue at Arthur Bryant’s. Hit up Kauffman Stadium for a Royals game. And make sure to leave an entire day for a visit to 18th and Vine. You won’t be disappointed.