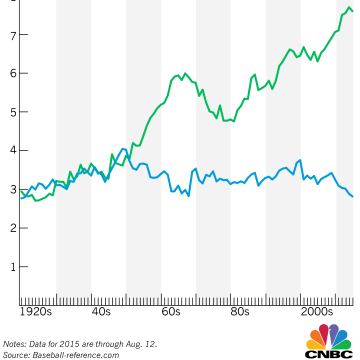

Walks in baseball are way down. Way, WAY down.

Through August, Major League Baseball saw an average of 2.8 walks per game. If the season were to end there, that would be the lowest level since the 1920s. Similarly, a lot of the stats show that pitching is dominant over hitting. Strikeouts are up, batting average is down, among other key statistics.

What’s going on here? Could the decline in offense be related to … the market?

“It’s like capitalism,” said Billy Beane. “You have a void that needs to be filled, and a whole generation of kids that see it.” Beane, the general manager of the Oakland A’s, has seen the leagues’ approach to pitching do a full 180.

“Back in the 1990s, there was a panic in the industry about lack of pitching,” Beane told CNBC. “Now you have a big wave of pitching that is physically so much different.”

Beane noted the increase in physical domination of today’s pitcher. “When I was playing, you might have a few guys that threw over 90 miles per hour, but now you have entire staffs where average velocity on fastballs is 2-3 mph faster than a few years ago.”

The average fastball in the first half of 2015 left the pitcher’s hand at 91.7 mph, according to Major League Baseball’s pitch(f)x database. That’s more than a full mph faster than the 2008 average of 90.6.

All-Star hitters agree. “The pitchers these days throw harder and can throw their off-speed pitches for strikes,” Mark Teixeira told CNBC. “They’re just better.”

The New York Yankees first baseman agreed with Beane that this year in particular has been different. “It is definitely getting hard to walk in the big leagues. I feel the trend started a few years ago and is getting more pronounced this season.”

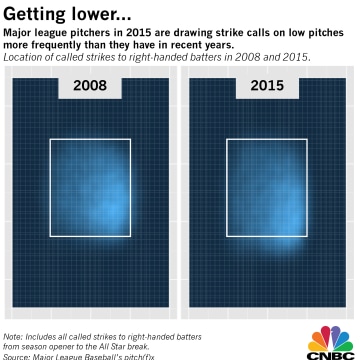

In addition, major league umpires seem to be letting pitchers get away with a bigger strike zone this year. The distribution of called strikes to right-handed batters in the first half of the season shows the increased use of the low ball.

“The larger strike zone, especially on the low pitch, hasn’t helped,” Teixeira said.

“You might have a Randy Johnson at 6’10” back in the 1990s, but now you have four to five guys who are 6’4″ to 6’6″,” Beane said.

He also pointed out the “specialization of pitchers” to come in for a single inning and “more sophisticated data than a few years ago.” That allows teams to “find the specific pitcher to exploit a batter’s weakness.”

Ed Feng, a sports data expert who runs The Power Rank subscription service, cited a classic baseball movie to explain the phenomenon. “In ‘Moneyball,’ we learned about on-base percentage as the most important stat. A hitter should get on base, even if it means taking a walk,” Feng said.

“The converse for pitching is that you shouldn’t walk guys. That just beefs up their OBP (on-base percentage),” he said. “If you look at some formulas for defense independent pitching, you find that not walking one batter is worth 50 percent more than striking that batter out.”

Yet maybe the hitters aren’t taking that lesson.

“For today’s player, striking out is not anything frowned upon,” said Rick Honeycutt, pitching coach for the Los Angeles Dodgers. “Twenty years ago, people prided themselves on not striking out.”

He gave an example with his all-star ace: “I see it all the time with Clayton Kershaw, the hitters know a fastball is coming, and they still want to swing.”

Honeycutt said he thinks the game has changed to the point “where everybody wants to be power: power arms or power bats — they want home runs. I see less guys willing to go the opposite way, especially with two strikes.”

He also noted similarly to Beane that the talent is on the pitchers’ side. “Bullpens are getting more powerful,” and “more teams are going to younger hitters, who don’t have that experience, and starting pitchers are going to take advantage of them.”

So what happens from here on out? Can batters come back? Here, Beane extends his markets analogy. “At some point there will be a correction. We may have this conversation about hitters in a few years: where’s all the pitching?”

He added: “I’ve seen lots of spikes: hitting, pitching, fielding. Capitalism will start filling those voids. You will see a wave of talent coming into that area, which you’ll expect in the hitting department.”

Eventually, that could put upward pressure on something else for which baseball is noted — its big salaries.

“Any normal market will tell you, when there’s a scarcity in something, that will increase the price,” Beane added.