Strikeouts Can’t Kill Baseball (or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying And Love the Whiff) – The Ringer (blog)

If you pay any attention to baseball, you know about the narrative that the sport is circling the drain. As my colleague Bryan Curtis chronicled, the first known assertion that baseball is dying dates from 1868, and the flood of cautionary notices and premature memorials hasn’t slowed since.

If you pay any attention to baseball, you know about the narrative that the sport is circling the drain. As my colleague Bryan Curtis chronicled, the first known assertion that baseball is dying dates from 1868, and the flood of cautionary notices and premature memorials hasn’t slowed since.

The latest alarm comes from Sports Illustrated’s Tom Verducci, in a piece published Tuesday. “What Happened to Baseball?” the article inquires. “Home runs and strikeouts are up, and it’s a problem,” asserts another tease. A story summary near the top of the page intones that those homers and strikeouts, coupled with the slowing pace of play, are “threatening the future of the national pastime.”

Verducci, who recently appeared on The Ringer’s MLB podcast, is one of baseball’s best reporters and storytellers, and among the most astute observers of the changes shaping the game. Every statistic and trend in his article is accurately conveyed: Pitch speeds, homers, and strikeouts really are increasing, as are game lengths and the time between pitches. Some small-ball tactics, meanwhile, are being abandoned, and pitcher appearances are shrinking in length.

I can’t question the numbers. Heck, I’ve highlighted them myself, contributing many of my own posts and podcasts to the pile of digital literature about homers, strikeouts, small ball, and bullpen usage. But the more I mull it over, the more I wonder whether these developments are existential threats, or whether they occupy an outsize place in the media’s — and commissioner Manfred’s — discourse about baseball.

Modern sports coverage favors hyperattentiveness to statistical trends. Thanks to sites such as Baseball-Reference and FanGraphs, we can quickly cast our eyes over the whole of baseball history. Every annual increase or decrease is neatly laid out on one page, with earlier eras a spin of the mouse wheel away. Ever-more-sensitive stats allow us to dig deep into every development, poring over the incidence of seemingly small-beans events such as wild pitches, sacrifice flies, ground-ball double plays, and calls of catcher’s interference. When something about baseball changes, somebody who spends a lot of time looking at leaderboards will blog about it. Inevitably, another reporter will ask the commissioner to comment on the change, which incites another round of reactions.

When we take a sport’s pulse so frequently, we’re bound to magnify every flutter. Sports turn us all into hypochondriacs on behalf of our teams, and when writers repress their partisan rooting, the impulse to find fault in and make mountains out of 25th roster spots expresses itself in hand-wringing about the health of the sport as a whole. While in theory there should be a strong correlation between what worries and fascinates sports-media members and what worries and fascinates fans, some obsessions are one-sided. Just as what’s trending on Twitter only faintly resembles the news in non-online life, thinkers in baseball’s sabermetric bubble might be overestimating how much the latest percentage-point uptick matters to the typical consumer who’s primarily watching one team and pulling for its players rather than stressing about strikeout trends. Although the most plugged-in people are the first to poke holes in ill-informed, overblown takes about baseball’s shrinking national TV ratings, they might be the most prone to perceiving seismic shifts in relatively subtle on-field trends.

Whether we imprinted an earlier version of baseball, are biased toward believing we live in interesting times, or simply have some column space to fill, it’s tempting to conclude that the league is approaching a reckoning. But for three reasons, I suspect that baseball’s supposed problems with homers and strikeouts aren’t as serious as some suggest.

The Changes Aren’t As Drastic As They Sound

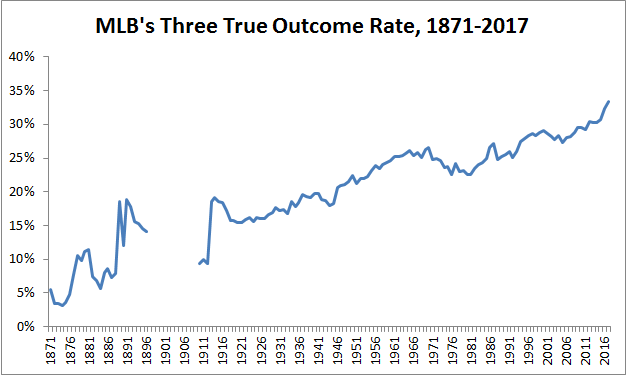

Let’s focus, as Verducci does for much of his article, on the three true outcomes — walks, strikeouts, and homers. Here’s a graph of the TTO rate throughout major league history, save for an early lacuna where we’re missing strikeout totals.

There are two ways to interpret that inclined line: (1) that this TTO-rate rise is inexorable and will eventually exterminate every ball in play, leading to the heat death of baseball; or (2) that the current trend is as old as the game, and that just as baseball has remained recognizably baseball throughout previous periods of increasing TTO rate, it remains recognizably baseball now.

I tend toward the more optimistic take. As obvious as the 140-year-old-long pattern is, and as steep as some of the concentrated spikes (such as the one we’re in now) are, the overall increase has been gradual. Even now, the differences seem small if you break them down on a per-team or per-game basis rather than focusing on full-season totals. For instance, MLB teams are on pace to break the all-time record for home runs in a season, set in 2000, by 493 dingers, and 493 dingers in a single season sounds like a lot. That’s 420 more than Barry Bonds’s best single-season total! But it’s also only a little more than 16 per team. And since each team plays 162 games, we’re talking about 0.1 more homers per team, per game, or one extra homer per team every 10 games. Of course, the uptick this year is more significant compared to the typical season. But baseball fans witnessed 2000, the previous record season, and lived to tell the tale. We’ll survive 2017, too, just as we’ll survive any modest increases still to come.

Here’s one more stat to put this in perspective. Last year, the average pitching staff allowed 4,294 batted balls, or 26.5 per game. In 1996, the average pitching staff allowed 4,523 batted balls, or 27.9 per game. In two decades, then, team batted-ball totals (including home runs) decreased by 5 percent, or 1.4 batted balls per team per game. One plate appearance out of every 20 has switched from producing a ball in play to producing a strikeout, walk, or home run. That’s not nothing, but it’s also not something you’d notice immediately if you weren’t already aware of the numbers.

Nor is the outcome of the balls that are put in play becoming any less uncertain. For all the fretting about defensive shifting and data-driven positioning, MLB’s batting average on balls in play this season is .299 — the same as it was in 2009, when the shift was just catching on, and higher than in any year between 1936 and 1994. Players are treating baseball-watchers to almost the same number of hits per game today as they did in 1985, 1975, 1961, or 1919. The types of hits have changed, but we’re still seeing action.

Whether the Changes Are Bad Is Debatable

In August 1997, 20 years before Verducci published his piece, SI ran a Kelli Anderson story whose headline declared, “Strikeouts are piling up at an alarming rate.” The text below warned that K’s were increasing at a “frightening pace,” and that “the concept of selfless offensive play has, regrettably, gone the way of the $3 bleacher seat.” If we want to go back a bit further, here’s Tim Kurkjian in July 1994, again in SI, worrying about “The Big Whiff,” and here’s Moss Klein in The Sporting News in January 1987, bemoaning baseball’s “Record Strikeout Parade.”

Now that we have some historical distance, we can ask ourselves whether, in retrospect, the 1997 strikeout rate should in fact have frightened or alarmed us. I would argue that the answer is “no.” For one thing, Anderson’s story arrived during a fifth consecutive season of increasing strikeout rates; K rates decreased in two of the next three seasons and in five of the next nine, which is a useful reminder that we’re not necessarily doomed to a new record rate every year. For another, even though strikeouts are more common now than they were in 1997, baseball has been awfully fun since then. If I ask you to mentally play back baseball over the past 20 years, the montage that goes through your head won’t have hitters swinging and missing set to Halloween-style dissonant strings. It will have, among many other events, the 1998 home run race, the Yankees dynasty, Pedro’s peak, a period of unprecedented competitive parity, the sabermetric revolution, the Red Sox and Cubs ending their title droughts, and Mike Trout. Although its status in American culture isn’t what it was before other sports rose to prominence, baseball’s ability to be memorable hasn’t decreased along with its contact rate, as our own recollections — and the sport’s record revenues and attendance in the decades since 1997 — would attest.

Naturally, no one is excited to see the same amount of on-field action take more time. And it seems safe to say that there’s some extreme of strikeouts, walks, and homers that no one would want: If every play ended with one of the three, we would find ourselves pining for those exciting squibbers back to the pitcher and good ol’ grounders to the right side. But within the wide range from, say, 15 to 50, the optimal TTO rate is a matter of taste. Higher is not necessarily worse, and doubling down on dingers seems as likely as any other on-field adjustment to recapture kids’ interest in a game that’s stereotyped as stodgy.

The cult of contact seems to presume that balls in play can’t also be boring, and we know that’s not true. What’s so exciting about a bouncer to second, followed by a half-hearted jog and a routine throw? For that matter, what’s so exciting about a single? I’d rather see someone hit a ball 400 feet or go down swinging at a spectacular pitch than most of the alternatives. And to the extent that this offensive environment is responsible for fewer sacrifice bunts (blah) and intentional walks (yawn), which Verducci lumps under a lament about “less strategy,” I’m grateful for the assist. Of the other three things that Verducci lists as endangered — hit-and-run plays, dedicated pinch hitters, and stolen bases — only the last one would be a big loss. Luckily, we’re not actually losing it: The stolen-base rate this season is exactly the same as the average from 1920–2016.

Earlier this week, Rob Manfred told Yahoo’s Jeff Passan that the league’s surveys suggest that fans are happy with the current rates of homers and strikeouts. We haven’t seen the survey results, but that takeaway wouldn’t surprise me. I like watching Chris Sale, Craig Kimbrel, and Kenley Jansen make other elite athletes look silly. I like watching skilled strike-stealer Yasmani Grandal deftly present a pitch. And if, like me, you’re enjoying the offensive fireworks from Aaron Judge and Cody Bellinger, I have news for you: Their combined TTO rate is 52 percent. The Ringer has written recently about all six of the players I named in the preceding two sentences. We have not written recently about, say, Eduardo Núñez, who doesn’t walk, strike out, or hit homers but hasn’t earned any adulation by putting balls in play.

Of course, there’s something to be said for variety, but we still have it: Something other than a strikeout, walk, or home run still happens two-thirds of the time. Again, the outcomes other than the three we’re supposed to be so worried about are still twice as common as that trio combined, and even at their recent rates of increase, the TTO outcomes would take years to close the gap. And there’s also something to be said for variety across eras. Even if we could poll the populace, determine the most broadly pleasing brand of baseball, and then automatically make the game’s conditions mirror the desired rates, we probably wouldn’t want them to stay the same forever. I like that baseball’s constant battle between offense and defense yields different conditions one decade than it does the next.

If the Changes Do Cause Problems, Baseball Has Options

I’m not saying that we shouldn’t take note of the ways in which baseball is changing. For one thing, it’s satisfying to pinpoint the cause of an effect. For another, it’s prudent for baseball’s analysts and executives to keep an eye on these increases, just as it is for NASA to scan space for big rocks that could kill us even though the odds are remote.

But it’s a large leap from “baseball is different” to “baseball is doomed.” Maybe this makes me sound Pollyannaish; one could, after all, apply some of the same arguments I’ve made about baseball to climate change, exchanging 1.4 batted balls for 1.4 degrees. But the topics aren’t analogous, and not just because baseball is a recreational activity and global warming is a potential extinction event. It’s not as if every tick of TTO rate is doing identifiable damage to some baseball equivalent of the Antarctic ice shelf. And baseball can tolerate TTO changes better than the human body can tolerate temperature changes: Baseball’s TTO rate has doubled in the past 90 years, and the sport has survived, but if the earth’s temperature doubled, we wouldn’t.

More than that, though, there’s a mismatch in the ease of implementing solutions. It’s easier to adjust a sport’s enclosed ecosystem than it is to stop emissions and reverse environmental damage on a planet-sized scale. Baseball has its intractable problems — because individuals’ incentives don’t always align with the league’s, it would be tough to talk pitchers into not throwing as hard, managers into abandoning specialized relievers, or hitters into taking more measured swings — but there are counters to each of those trends.

Here’s a complete list of everything MLB has tried recently to slow or reverse the rising TTO rate: nothing. If anything, baseball has taken steps to make strikeouts more common, first by lowering the zone’s bottom boundary in 1996 and subsequently, in the past several years, by enforcing the rulebook strike zone in a way that has effectively increased the size of the called strike zone. Moreover, MLB isn’t the Federal Reserve, wondering “What now?” after slashing interest rates to zero. There are many means at MLB’s disposal if the sport can’t course-correct organically and the league does decide to do something about TTO rates or renew its efforts to improve pace. The strike zone, which has expanded, could be compressed. The mound could be lowered or moved back. Outfields could be bigger. The NL could add the DH (although that would add homers while cutting K’s). The pitch clock could be ported to the big leagues. Pitching changes could be slightly restricted. Baseball has intervened before, most notably by lowering the mound and restoring a smaller strike zone after offense bottomed out in 1968, and its tinkering had the intended effect. For years, no new record was reached; the 1969 TTO rate wasn’t surpassed for good until 1994.

That parable about the frog unwittingly boiling in gradually warming water is bunk. When the water gets too warm, the frog tries to jump out of the pot. So will Major League Baseball, if and when conditions call for it. That the league hasn’t yet acted is a sign, but the sign isn’t saying that baseball’s potential problems can’t be fixed. It’s telling us that we haven’t actually come to a crisis.

Thanks to Steven Goldman of FanRag Sports for research assistance.