In early summer 1859, St. George’s Cricket Club found itself at an existential crossroads. Established in 1838, the Manhattan-based organization had for decades worked assiduously to, in the words of an 1859 club pamphlet, “see Cricket more generally established, better understood, and more regularly practiced” in America. In this quest, the club had initially benefited from its sport’s old-world cachet. Cricket offered American sportsmen a uniform and replicable product. Conversely, its chief competitor—“Base Ball”—had until recently remained provincial and largely underdeveloped.

This advantage had long kept cricket competitive in a battle for supremacy in New York, which was far more hotly contested than modern sports fans might think. “In the mid-1850s baseball and cricket were reasonable contenders for the title,” says John Thorn, the official historian of Major League Baseball. “The press often referred to them [in the plural] as America’s ‘national pastimes.’”

In those years, however, baseball had taken significant strides. In 1854, New York’s most prominent clubs, led by a team known as the Knickerbockers, had begun to codify basic rules. The sport’s popularity grew exponentially after an 1857 conference established many of the standards that remain in place today. With new clubs sprouting monthly across the northeast United States, St. George’s and other cricket organizations now searched for something, anything, to stave baseball’s momentum.

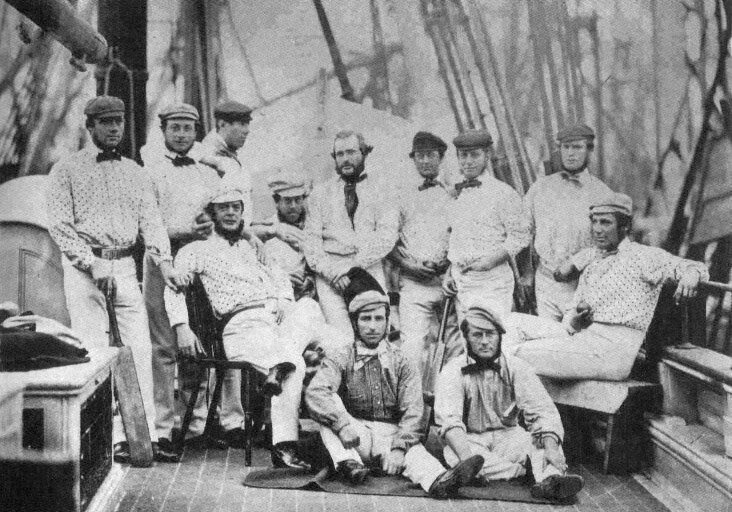

On June 9, 1859, they found it. For years, St. George’s, along with a peer club in Montreal, had tried to lure the All-England Eleven—a world-renowned all-star team of British cricketers—to North America. On this day, the club received word that their efforts had finally paid off. The team, spearheaded by George Parr, “the great Leviathan of Batters,” had committed to October fixtures against clubs at Montreal, New York City, Philadelphia, and Hamilton.

Founded by William Clarke in 1840, the All-England Eleven included several of the era’s most famous players. In addition to Parr, the Eleven included such notable personalities as James Grundy, who in July 1857 had famously scored 108 runs in six straight hours; Robert Carpenter, a fielding wizard “as active and playful as a young colt turned loose in his pasture”; and John Jackson, a man “notorious for the terrific celebrity of his bowling.”

Intrigued to see their countrymen take on such storied talent, Americans went suddenly mad for cricket. Newspapers as far away as Louisiana and Wisconsin promoted the matches, alongside basic rules, terms, and strategies for the sport. As one member of St. George’s later recalled: “No arrival in this country from England could have produced greater excitement than these celebrated Cricketers have done, except a visit from Queen Victoria herself.”

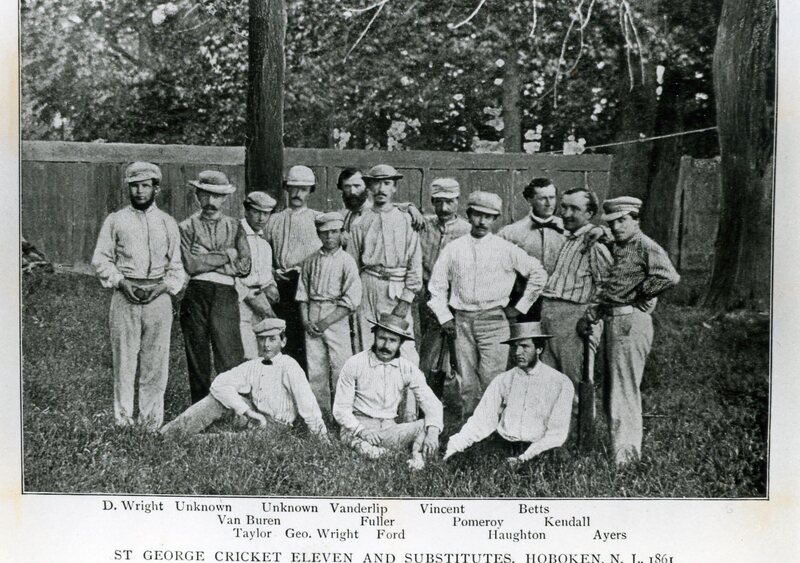

Of the four fixtures, the New York match stood out as the main event. Dominated by members of St. George’s, the squad there brimmed with experienced players—most notably Harry Wright, whose father, Samuel, had been a professional cricketer in Sheffield, England. Wright, who would later manage America’s first fully professional baseball team, the Cincinnati Red Stockings, already boasted enough of a reputation in New York to inspire hope for a legendary upset.

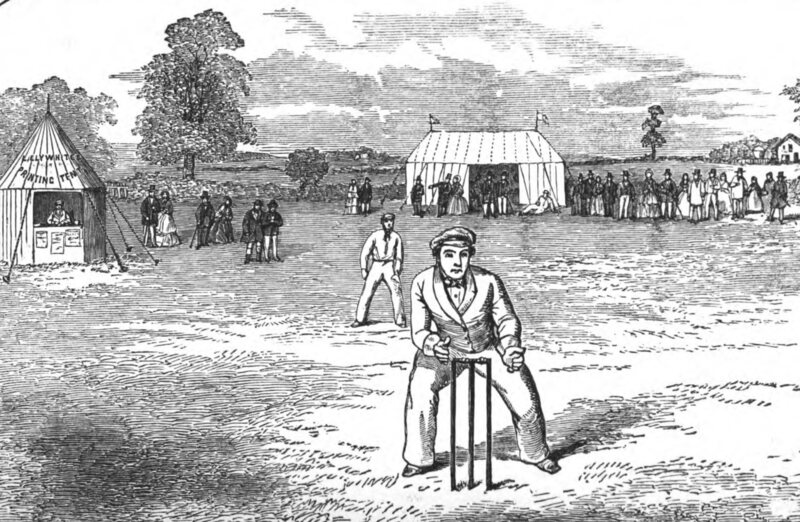

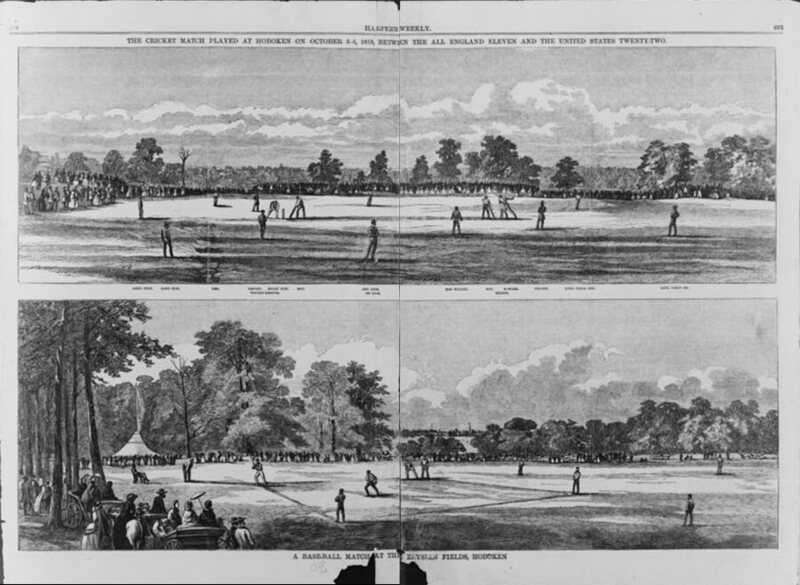

By October 3, game day, anticipation reached a fever pitch. According to St. George’s account of the match, attendees filled all 5,000 seats set up at Hoboken’s Elysian Fields, and “a large number were standing about in every eligible position from which a view of the ground could be obtained.” By the time the match commenced, “young men and maidens, old men and children” watched on with bated breath.

In a two-inning match, the umpires allowed the American side 22 batters. The English side batted the traditional 11. In their first inning, the Americans managed 38 runs before their final batter was out. The first two English batters alone put up 59. By inning’s end, the Eleven had scored 156 runs. The Americans did better in the second, notching 54 runs the next day. Still, they fell far short of the 118 needed to prolong the match.

Despite the thrashing, St. George’s spun the fixture as a success. Noting that the event had drawn “the largest array of spectators that had ever previously been congregated for such an object in this country,” the group later wrote that the young American players needed “only the right practice to equal ere long in expertness, any men or set of men from the parent country.”

To the club’s dismay, however, control of the post-match narrative soon slipped out of its fingers. Shortly after the Eleven defeated another opponent in Philadelphia, rumors proliferated that American clubs had challenged the cricketers to a game of baseball. The New York Herald reported on Oct. 13 that the Eleven had declined for the present, but had “obtained books of instruction and a specimen bat, and during the winter and spring [would] practice the game.” The following year, the paper continued, the club would “change position with their American friends, and become students instead of professors.”

The match never came to fruition. Still, the ensuing media blitz marked an important stage in the development of organized sports in America. For perhaps the first time in its young history, organized baseball found itself on the front page of a major American newspaper.

On October 16, 1859, the Herald ran a lengthy essay entitled, “Cricket and Base Ball: The English Cricketers and the Proposed Base Ball Match—the Two Games Described and Compared.” Intended for the uninitiated, it described both sports in the simplest of terms.

“Baseball,” the paper reported, “is so called from the game being played by a ball struck with a bat, whereupon the striker runs to points called ‘bases,’ of which there are four, at the four corners of a square, placed diagonally or diamond wise.”

After describing baseball’s basic rules, the article detailed recent innovations, including the expansion of foul territory, the requisite 90 feet between bases, and, notably, force outs: “Formerly it was sufficient to strike the adversary with the ball by throwing it at him. This practice is now abolished, as it was dangerous and unnecessary to the game.”

Unfortunately for St. George’s, the Herald didn’t stop there. The paper went on to choose sides in a debate then raging about whether cricket or baseball had the most potential to draw paying crowds. “In the points on which it differs from cricket, [baseball] is more suited to the genius of the people,” it argued. “Even if there were no base ball in existence cricket could never become a national sport in America—it is too slow, intricate and plodding a game for our go-ahead people.”

Declaring baseball much livelier than its competition and admiring how the sport could be played in a single afternoon rather than cricket’s two to five days, the paper then delivered an incisive line, which spelled doom for cricket in a post-Jacksonian America. “Cricket seems very tame and dull after looking at a game of base ball,” the paper declared. “It is suited to the aristocracy, who have leisure and love ease; base ball is suited to the people.”

Despite such coverage, St. George’s patrons remained hopeful. The tour of the All-England Eleven had proven a resounding financial success. Assuming, perhaps correctly, that the Eleven would never risk embarrassing itself in a baseball match, St. George’s wrote off reports of an exhibition match as unfounded rumors. The club hoped to lure Parr and his all-stars back across the pond as soon as possible. Should American squads make a better showing during a rematch, the club might restoke the excitement that had preceded the Eleven’s arrival.

Unfortunately, such plans soon fell victim to the whims of history. Initially, St. George’s had eyed dates in 1861 as reasonable options for a return visit. “The Civil War made this impossible,” Thorn says, “not only for logistical reasons, but also because it enflamed anti-England sentiment.” New Yorkers, like many northerners, resented Great Britain for continuing to buy Southern cotton during the war.

By the end of the conflict, interest in cricket had waned. While the sport remained respectable, it was too foreign, too British, to appeal to a divided populace desperately searching for a new national identity. As the reunited states pieced themselves back together in subsequent years, it became clear there was only one game perfectly suited for American sensibilities.

“What cricket is to an Englishman so base ball is to an American,” the Herald wrote in its preview of the 1867 season. “Each look upon their national game as the very perfection of a sport; and nothing would be better adapted to the peculiar characteristics of the two nationalities than these very games.”