The End of Baseball As We Know It – The Ringer (blog)

Welcome to Inefficiency Week. Over the next five days, we’re going to take a look at what we lose when we get lost in the chase for efficiency. We’ll explore the ways it’s changing the games we love to watch. We’ll remember its failures across the pop culture spectrum. And we’ll report on what it’s doing to our lives — romantic, physical, and otherwise.

When I was a little kid, my family went to a Southern Baptist church, where every Sunday morning we heard a sermon from Pastor David. I’ve known many men and women of the clergy, but more than any of them Pastor David was a preacher. He had a warm, broad smile, a sonorous baritone voice, and a penchant for peppering his speech with literary flourishes like “the downward spiral of sinful disbelief.” He’d have been wasted on any other profession.

When I was a little kid, my family went to a Southern Baptist church, where every Sunday morning we heard a sermon from Pastor David. I’ve known many men and women of the clergy, but more than any of them Pastor David was a preacher. He had a warm, broad smile, a sonorous baritone voice, and a penchant for peppering his speech with literary flourishes like “the downward spiral of sinful disbelief.” He’d have been wasted on any other profession.

One Sunday, Pastor David delivered a sermon titled “How to Boil a Frog.” It had never occurred to me before that someone might want to boil a frog, much less a live one. But the parable of the boiling frog turns out to be quite popular, and it goes like this: Throw a live frog into a pot of boiling water and it will jump out, but if you put a frog in a pot of lukewarm water and turn up the heat gradually, the frog won’t notice that anything’s wrong until it’s too late for him to escape.

This isn’t actually how you’d boil a living frog, but the metaphor remains in common use to represent any number of sneaking threats, from climate change to civil rights to, in baseball’s case, the creeping takeover of the Three True Outcomes: strikeouts, home runs, and walks.

Baseball has never looked quite like it does now, for better and for worse. Defenders are getting involved in play less than ever and stolen bases are at a 45-year low, but on the other hand, the game is populated by beastlike men capable of spectacular feats of power. And the sport is only moving further toward that extreme. Barring some strategic correction or a rule change, the water will boil soon, if it isn’t boiling already. But since it happened so gradually, it still feels like it’s the same temperature.

The phrase “Three True Outcomes” was coined in 2000 by then–Baseball Prospectus writer (now Ringer contributor) Rany Jazayerli. “Together, the Three True Outcomes distill the game to its essence,” he wrote, “the battle of pitcher against hitter, free from the distractions of the defense, the distortion of foot speed or the corruption of managerial tactics like the bunt and his wicked brother, the hit-and-run.”

The phrase “Three True Outcomes” was coined in 2000 by then–Baseball Prospectus writer (now Ringer contributor) Rany Jazayerli. “Together, the Three True Outcomes distill the game to its essence,” he wrote, “the battle of pitcher against hitter, free from the distractions of the defense, the distortion of foot speed or the corruption of managerial tactics like the bunt and his wicked brother, the hit-and-run.”

The turn of the century was the heyday of defense-independent pitching (DIPS) theory, the brainchild of an early sabermetrician named Voros McCracken. In one of the first great research breakthroughs of the public baseball research movement, McCracken found that pitchers can only truly control three things: strikeouts, walks, and home runs. If the batter made contact and the ball came down in front of the fence, what happened to it depended on numerous other factors ranging from the skill and positioning of the defenders to the length of the grass and coarseness of the infield clay. You could learn a great deal about a pitcher by removing those other, more difficult-to-quantify factors and distilling his numbers to the Three True Outcomes.

DIPS theory has itself been challenged in the nearly 20 years since its introduction as our understanding of the game has evolved and our ability to quantify defense and batted-ball factors has improved, but the basic concept still has had an immense impact on the game.

We know now that not all pitchers will necessarily regress to a league-average BABIP and that some have the ability to induce weak contact. But missing the bat entirely is still better, so that’s what modern pitchers are taught to do. Meanwhile, batters are trying to avoid defenders — particularly defenders who use batted-ball data to shift into advantageous positions — by hitting the ball over the shift, if not over the fence.

Pitchers are pursuing strikeouts and batters are pursuing home runs, and both are wildly successful at the moment.

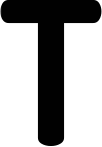

FanGraphs has records of average pitch velocity dating back to 2007, when the PITCHf/x tracking system was first implemented in MLB ballparks. Here’s the league-wide average fastball velocity over that time, along with league average strikeout, walk, and home run rates. (The 2017 numbers are updated through July 30.)

Walks and home runs have fluctuated, but average fastball velocity has increased every year since 2009. Baseball Reference has league-wide strikeout, walk, and home run totals from every major league season since 1871. The league-average strikeout rate has risen every year since 2006, and set a new all-time record every year since 2008. Recent home run trends are muddled somewhat, since home runs rose during the steroid era, then temporarily dropped with the introduction of drug testing in 2004, before rising again (with a brief dip from 2012 to 2014) to the present. But this year, teams are hitting 1.26 home runs per game, which beats the previous all-time high, set in 2000, by 7 percent.

That brings us back to the boiling frog. Since 2007, average fastball velocity has never risen more than 0.4 mph from one year to the next. The league-wide home run rate hasn’t risen more than 0.15 home runs per game, and strikeouts haven’t risen by more than 0.4 per game. You’d never notice that change year to year just by watching the game, but compared to 2007, home runs are up 23.5 percent, strikeouts are up 24.8 percent, and fastball velocity has increased by 1.6 miles per hour, or roughly the difference between Clayton Kershaw and Clayton Richard. Overall, the number of at-bats that end in one of the Three True Outcomes is up 18.4 percent since 2007. Taken as a whole, those increases are quite noticeable.

“There’s no doubt the pitchers throw harder now than when I first got to the league, but there is also a different mentality from players these days,” said Houston designated hitter Carlos Beltrán, who’s now in his 20th MLB season. “They feel like if they strike out, it’s not a big deal. I personally hate strikeouts … but that’s my mentality. Yes, I see more homers and more strikeouts, but I guess that’s, like, the new baseball.”

Beltrán’s right. Many younger players don’t care that much about striking out, including one who TTO’d his way to superstardom over the past four months.

“I’m looking middle of the plate, middle of the field, trying to drive something to center field, and stick to that every pitch. Every pitch. Every pitch. No matter what happens,” said Yankees right fielder Aaron Judge. “If you miss the first one, if you take the first one, if it’s 3–2, 0–1, 1–1, doesn’t matter. Stick to it.”

The only one of the Three True Outcomes that isn’t on the rise is walks. While strikeouts and home runs are at an all-time high in 2017, the league-wide walk rate this year is just the 56th-highest since 1871. Walks are as common now as they were in 2007, and down almost two percentage points from the all-time high of 10.4 percent in 1949. This season, only three of 71 qualified starters — Tyler Chatwood, Wade Miley, and Robbie Ray — are walking a higher percentage of batters.

The only one of the Three True Outcomes that isn’t on the rise is walks. While strikeouts and home runs are at an all-time high in 2017, the league-wide walk rate this year is just the 56th-highest since 1871. Walks are as common now as they were in 2007, and down almost two percentage points from the all-time high of 10.4 percent in 1949. This season, only three of 71 qualified starters — Tyler Chatwood, Wade Miley, and Robbie Ray — are walking a higher percentage of batters.

Walks are a measure of a pitcher’s skill and tactics: Can you pick your targets wisely and hit them? Home runs and strikeouts are more reliant on brute force: Can you mash this ball 400 feet or can you throw it 100 miles an hour?

Either way, it takes strength to play in the big leagues, and today’s athletes are bigger and stronger than ever. Again, this change is gradual but with pronounced long-term effects. From 1901 to 1960, there were 76 big leaguers total listed at 6-foot-5 or taller. Two-thirds of the way through the 2017 season, there are 133 and counting this year alone. Mariners outfielder Jarrod Dyson, who ranks 149th out of 164 qualified hitters in isolated power, is listed at 5-foot-10, 165 pounds. Willie Mays, who hit 660 home runs, was listed at 5-foot-10, 170.

As the athletes are getting bigger, the field is not. The bases have been 90 feet apart since the mid-19th century, and the distance between the mound and the plate was set at 60 feet, 6 inches in 1893. Bigger, longer-limbed, harder-throwing pitchers have to cover the same distance as Kid Nichols. No wonder strikeouts are at an all-time high.

Not only are the athletes getting better, so are the people recruiting and training them. In Beltrán’s lifetime, the cutting edge of baseball research has gone from a stack of index cards in Earl Weaver’s office to the musings of amateur statisticians and theorists to all 30 teams being run by business school types backed by an army of empiricists. The professionalization of the front office has been the only change in baseball over the past 20 years more marked than the increasing strikeout rate.

Modern coaches and executives are awash in data and obsessive about teaching players what they know works. Mets pitchers learn the Warthen Slider, named for pitching coach Dan Warthen, while Yankees and Dodgers farmhands get taught a series of mechanical tweaks that add fastball velocity. Rookie left-hander Jordan Montgomery of the Yankees came out of college throwing 88 to 91 mph and did so until he ran into pitching coach Tommy Phelps in high-A.

“[Phelps] kind of sat me down and said, ‘Hey, I don’t think you’re going to get to the big leagues like this. You got way too much leverage and you’re not using it, so let’s try something,’” Montgomery said. “I did a couple drills, and the next game I went out there and I was 91–95. I was like, ‘I’m all in on it now.’ ”

Montgomery, who now has a 111 ERA+ in 20 starts, didn’t evolve. He just changed.

“It literally took a week,” Montgomery said. “I threw six perfect in Daytona. … Ever since then I’ve been doing what he said.”

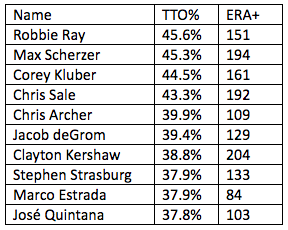

Throwing harder and striking more guys out sounds intuitive enough, but in case there were any doubts, here are the top 10 qualified starters this year in TTO percentage.

It’s possible to have success at the other extreme by limiting home runs and walks — Iván Nova, Michael Fulmer, and Alex Cobb all have done so this year, among others — but the list of the top TTO starters in baseball looks an awful lot like a list of the best pitchers in baseball by any standard.

The advantage of a TTO-heavy approach isn’t as immediately plain for hitters, because the most common of the Three True Outcomes, strikeouts, is a bad outcome for the offense. Trevor Story (74 wRC+) is striking out 36 percent of the time this year; Carlos Correa’s entire TTO% is 35.9, while his wRC+ is 158. But Judge, the MLB leader in wRC+, is second in TTO% at 55.2. Of the 25 top TTO hitters in baseball, 20 have a wRC+ of 100 or better, compared to just 14 of the bottom 25. And that’s underselling the advantage.

Of the top 25 hitters in wRC+, 18 have a TTO% higher than the league average of 33.4 — frequently much higher. Those 18 hitters include Judge, Bryce Harper, Correa, Paul Goldschmidt, Michael Conforto, Corey Seager, Cody Bellinger, The Mighty Giancarlo Stanton, Joey Votto, and Kris Bryant. Mike Trout doesn’t have enough plate appearances to make this list, but his TTO% is 44.4. These are the best offensive players in baseball.

The highest TTO% of any qualified hitter belongs to Joey Gallo of the Texas Rangers, a career .190 hitter who, thanks to high power and walk numbers, in addition to the ability to play third base, is nonetheless worth a win above league average for every 650 plate appearances, according to Baseball Reference.

“Obviously I’m not trying to strike out,” Gallo said. “But I think it’s better for the player I am to go up there and swing the bat with some intent than just stick the bat out there and [say], ‘Well, I just hit a ground ball to the second baseman.’ ‘Well, he put it in play but he’s still out.’ You know, I’d rather at least try to put a good swing on it, and if I miss it, I miss it. But if I hit it, damage is going to happen.”

Even hitters without Gallo’s strength benefit from two running stories this year: the juiced ball and the swing-plane revolution. This home run revolution is unlike the steroid era in that nobody’s hitting 60 home runs a year, but everyone’s hitting 20.

In 2016, 111 players crossed the 20-homer plateau, the most in history, including little guys like Freddy Galvis. In 2017, Ryan Schimpf, listed at 5-foot-9, 180 pounds, is hitting .158/.284/.424 in 197 PA, with a TTO% of 56.3. The new, chic swing path, which involves a slight uppercut to get the ball in the air, has some well-documented converts, including Justin Turner, who went from a utility infielder to an MVP candidate, and Yonder Alonso, who suddenly discovered a power stroke in his eighth big league season.

“The game is always changing and you gotta try to change with it,” said Astros right-hander Mike Fiers. “As a pitcher, you see guys changing their swings for, you know, trying to hit more home runs than for average. Guys are getting paid more, I think, to hit home runs and drive in RBIs, rather than hit .300. So you can’t doubt the guys for changing their approach, because that’s what teams want.”

If there’s a generational divide among hitters on the TTO issue, it rests on whether there’s inherent value in putting the ball in play. Beltrán says there is, but the 23-year-old Gallo, who played with Beltrán for a month last year on the Rangers, views strikeouts as just another out, because that’s the way he was taught.

“I mean, hell, our team — we have a meeting every day,” Gallo said. “‘Oh, you guys struck out 10 times.’ And you say, ‘Oh, who cares?’ Pitching is so good now. There’s specialists for everybody. Strikeouts are going to happen, and I think guys now see the importance of being able to drive the ball out of the park and what that does to help win games. It seems like younger players, myself included, like going up to the plate with the intent to do damage. There’s going to be some repercussions for that: You’re probably going to strike out a little more, too.”

In 2017, 58.8 percent of Gallo’s plate appearances have ended in one of the Three True Outcomes, which is just a preposterous number. Jayazerli’s original TTO article invoked Rob Deer, who’s the patron saint of the all-or-nothing hitting approach for people my parents’ age. Deer was a career .220/.324/.442 hitter with a TTO% of 49.1, which would rank eighth in baseball in 2017. This season, Gallo’s hitting .197/.312/.512, and while Deer was a bad defensive right fielder, Gallo’s within a couple runs of average at third base, despite being two inches taller and 25 pounds heavier than Deer.

Not that playing an infield corner in the age of the juiced ball and Three True Outcomes is easy.

“Recently, I’ve been playing first, and I’m holding guys on, and there’s like a big lefty at the plate, I’m like, ‘Holy shit. This guy is going to hit one down my throat right here.’” Gallo said.

Third on the TTO% list is Miguel Sanó at 53.0. Sanó’s having a better season than Gallo, with a 129 wRC+, but his underlying numbers and approach are similar.

“[Sanó isn’t] trying to hit a single,” said Fiers, the day after he’d held Sanó to two strikeouts and a foul pop behind third base in three at-bats. “He’s not trying to just get on base. He’s trying to drive the ball, so, he’s looking for a mistake. He’s going to burn you if you leave the ball up in the zone.”

At times, Fiers has struggled to keep the ball in the park this year — he allowed at least one homer in each of his first nine starts of 2017, and 18 total over that span — but he still says he prefers to face a masher like Sanó than a high-contact hitter, because it’s easier to get the likes of Sanó, Gallo, and Judge to strike out.

Meanwhile, pitchers are complaining that the ball is flying out of the park. Montgomery hasn’t been in the majors long enough to have played with the un-juiced ball that was used until mid-2015, and Gallo was only up for a month before the change, but both say they can tell the difference between an MLB ball and a minor league ball, and both prefer the former.

“The minor league balls are like hitting a wad of toilet paper,” Gallo said.

“They move differently,” Montgomery said. “The seams are bigger on minor league balls, so if you throw a major league ball and you cut it a little bit, it’s going to cut more. It’s easier to manipulate.”

Strikeouts and home runs are in many ways connected. Swinging harder leads to more home runs, but also more swings and misses. Stronger athletes mean the ball is both pitched and hit faster. Lower-seamed baseballs move more but also carry better. And strikeouts aren’t a sufficient deterrent to keep hitters like Gallo, Judge, and Sanó from working deep counts and swinging for the fences, while the best way for a pitcher to avoid surrendering home runs is to avoid surrendering contact of any kind.

The TTO revolution isn’t really a revolution at all — it’s the combination of numerous, individually imperceptible and seemingly unrelated factors, all driving the game toward a certain, ideally efficient end.

It’s unlikely that training and tactics will evolve in such a way that literally all contact will result in a home run, so the increase in strikeouts and home runs has to end somewhere. But we don’t know where that evolution will end, or when that end will come. The league-wide TTO rate increased 10 percentage points between the founding of the American League in 1901 and the start of the expansion era in 1961. It went up 5.1 percentage points from 1961 to 2014, and 3.1 percentage points from 2014 to 2017. Strikeouts have generally increased over time, but over the past decade that rate of increase has kicked up a notch.

It’s unlikely that training and tactics will evolve in such a way that literally all contact will result in a home run, so the increase in strikeouts and home runs has to end somewhere. But we don’t know where that evolution will end, or when that end will come. The league-wide TTO rate increased 10 percentage points between the founding of the American League in 1901 and the start of the expansion era in 1961. It went up 5.1 percentage points from 1961 to 2014, and 3.1 percentage points from 2014 to 2017. Strikeouts have generally increased over time, but over the past decade that rate of increase has kicked up a notch.

For example, 20 years ago the all-time single-season record for strikeout rate by a reliever was 38.5 percent, set by Rob Dibble in 1992. Since 1998, that record’s been broken five times by four different pitchers, and from 1998 to 2016 there were 31 different reliever seasons with a K% of 38.5 or better. This year, six different relievers with at least 25 appearances are on pace to either tie or beat Dibble’s 1992 mark.

Combine that with the swing-plane revolution and the juiced ball, which put a dinger on every bat the way Herbert Hoover promised to put a chicken in every pot and a car in every garage, and we live in the TTO era. When a period of baseball’s history has been defined by its style of play, it’s usually because that era is particularly low-scoring (the pre-1920 dead-ball era) or high-scoring (the steroid era). But the baseball of 2017 is neither — the average team is scoring 4.66 runs per game, the 64th-highest mark in the 147 years for which Baseball Reference has data.

What characterizes this era is that fielders play less of a role than ever. With the league-wide TTO rate at 33.4 percent, a third of at-bats involve only the catcher, hitter, and pitcher; between seven and 10 other guys (depending on how many men are on base) are left just standing around. For six batters (Gallo, Judge, Sanó, Matt Davidson, Khris Davis, and Trevor Story) and five relief pitchers (Dellin Betances, Corey Knebel, Craig Kimbrel, Carl Edwards, Jr., and José LeClerc), it’s a 50/50 proposition or better that the defense will not be needed.

When home runs come so cheaply, there’s a secondary effect of a reduction in stolen bases. In 2015, 2016, and 2017, there’s been an average of 0.52 stolen bases per team per game, tying the past three seasons for the lowest mark since 1972. That’s not only because teams value big, strong guys like Gallo over small, quick guys like Dyson (though Gallo’s 10-for-10 in stolen base attempts in his career), but because players who can run are choosing not to.

“I think guys are hitting for more pop, and more extra base hits, so they’re saving their bodies because they’re producing at the plate,” said Dyson, who ranks fifth in MLB with 23 steals. “So you got guys like [José] Altuve who pick a spot because, you know, he’s swinging the bat so good, he’s not going to run his legs into the ground.”

As a competitive enterprise, a game that involves fielders and baserunners progressively less and less is neither good nor bad; it just is. But efficiency is a concept completely unconnected to happiness or entertainment, which ought to be the end product of a game. For the most part, players understand that they’re entertainers, but they still care less about fun than winning.

“Homers are great,” said Beltrán. “The fans really get a kick out of it, and if they see more than one, then it’s even more fun, but at the end of the day teams are going to be judged by wins or losses. So I care a lot about winning ball games.”

There’s a point at which baseball might become so TTO-heavy, so characterized by station-to-station baserunning, that the sheer level of standing around will make the game boring. And every fan has a different ideal style of play — mine is best characterized by a line from The New Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract: “Baseball is supposed to be played by young guys who can run, rather than old fat guys who can hit home runs.”

But Judge’s immense national popularity suggests that I’m in the minority.

“It’s starting to become a fun time to watch baseball,” said Gallo. “Who the hell doesn’t want to watch [Judge] hit? Every time he comes to the plate, even if you’re not a baseball fan, you’re going to watch that guy hit.”

Gallo cites the home run chases of 1998 and 2001 as formative childhood experiences for him as a baseball fan, and as the next generation of ballplayers grows up watching players like him, in 20 or 30 years we might start to forget that baseball was ever not this TTO-heavy.

We’ll learn to accept any change if the heat gets turned up slowly enough.