The power is out in Northern California. More than 1 million Californians are now without electricity, one of modern life’s essentials that is frequently taken for granted. The blackout was done on purpose—to prevent sparks from powerlines that could ignite deadly wildfires.

Before planned blackouts are through in two or three days, as many as 3 million Californians may go without power. On the surface, the blackout and its causes are simple to understand. But the deeper causes are complicated, span decades of public policy, and dozens of overlapping unintended—and intended—consequences of decisions, both related and unrelated.

The wind in Northern California is blowing in from dry Nevada, as it often does this time of year. It’s called the “Diablo wind.” In Southern California, the comparable current blowing in from the Mojave Desert is known as the “Santa Ana winds.”

In both cases, as the wind rises above California’s mountain spine, then descends, it compresses and heats up. Forests, chaparral and brush, dry this time of year in California’s Mediterranean climate, are primed for wildfires.

This Isn’t Climate Change

Michael Wara, Stanford University’s director of climate and energy policy, warns, “We are having to adapt to new circumstances brought about by climate change.” He estimates that this week’s blackout could cost the state as much as $2.6 billion in lost economic activity.

Politicians, journalists, and some scientists repeat a common refrain: California is getting hotter and drier because of climate change. They ignore the fact that annual precipitation totals over the past 100 years show no statistically meaningful trend.

There are plenty of examples of California’s fires being blamed on climate change. Last year’s Sacramento Bee editorial about the deadly Carr Fire in Northern California was typical: “The Carr Fire is a terrifying glimpse into California’s future,” it declared, adding, “This is climate change, for real and in real time. We were warned that the atmospheric buildup of man-made greenhouse gas would eventually be an existential threat.”

But California, unlike the rest of the nation, receives most of its moisture in the winter and the months bracketing it, while getting precious little rainfall during the summer. Further, California is drought-prone, and has been for as long as scientists can determine from tree rings and sediment records.

The bottom line is that California has always had a high threat from wildfires and always will. The issue is how will that threat be managed, accommodated, or avoided?

Politicians Blame Utilities Instead of Themselves

Democratic state Sen. Jerry Hill (with whom the author served in the California State Assembly from 2008 to 2010), represents many of the people who are without electricity. He called the blackout an overreaction, saying, “I think they (PG&E, the region’s utility monopoly) need to spend the billions they’ve already received to harden the system.”

Gov. Gavin Newsom, a Democrat, supports the blackout as a preventive measure, noting that the planned power cut “shows that PG&E finally woke up to their responsibility to keep people safe.” So more than 1 million Californians had their electricity cut off today as the northern California electrical monopoly, PG&E, was forced to shut down its powerlines for fear of starting deadly wildfires.

Politicians blame PG&E for the recent fires that have ravaged the state, but some of the blame redounds to the politicians. Wildfires in recent years have grown more deadly because timber harvesting and brush clearing were greatly curtailed due to myriad environmental restrictions. In the meantime, crucial infrastructure investment targeted at improving the reliability and safety of powerlines has taken the backseat to the state’s demands for a huge increase in renewable energy—some of which, ironically, has necessitated the need for more powerlines to connect remote wind farms with the urban centers.

Look to Mismanagement of Forests

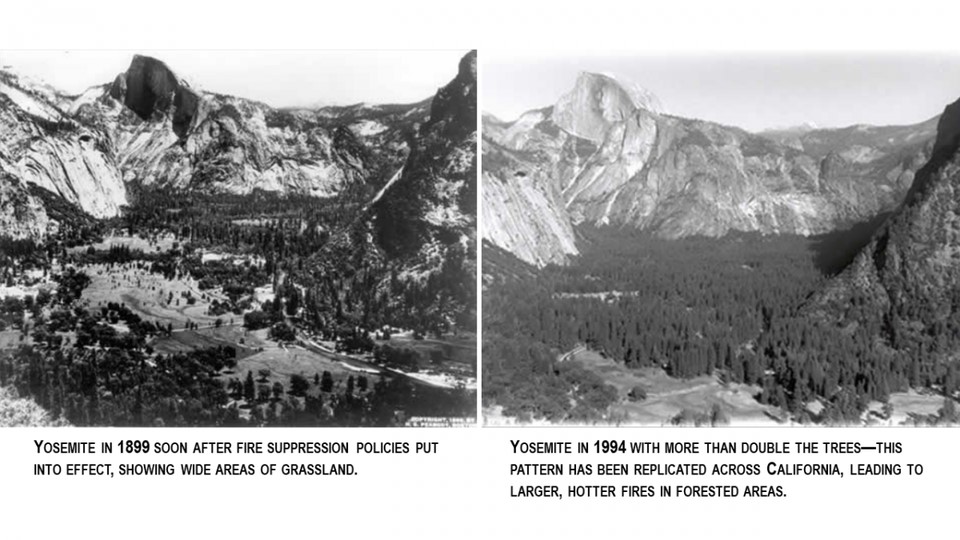

To better understand how we came to today’s blackout, it is useful to look to the past. When the gold rush led to modern California, early photographers chronicled the landscape. In George E. Gruell’s 2001 book, “Fire in Sierra Nevada Forests: A Photographic Interpretation of Ecological Change Since 1849” the wildlife biologist depicted a California countryside of grassland with isolated stands of pines and oaks. The native Americans in the region frequently used fire to shape the landscape to increase the food available for them, as not a lot of sustenance grows on a dense forest floor.

![]()

In this environment of frequent fire, brush was thinned, and the first pine branches started just out of reach of a typical low-intensity grass fire. But with the arrival of hundreds of thousands of Americans came a thriving economy and the order of government. Trees were useful and valuable, and therefore harvested. Fire was a threat to towns and cities, and thus, suppressed.

For decades, up until the 1970s, California would harvest and replant about as much wood as could be grown through an abundance of sunshine, snow, and rain. But in the 1990s, concern over logging’s effect on the spotted owl (largely misplaced, as time would tell) led to a massive slowdown in the timber harvest, especially on the federal lands that make up about 60 percent of California’s forests.

With a decline in the harvest came a decline in the allied efforts to clear brush, build and maintain access roads and firebreaks. This led inexorably to a decades’ long build-up in the fuel load. Federal funds set aside for increasingly unpopular forest management efforts were instead shifted to fire-suppression expenses.

All of this was clearly foreseen by the Western Governors’ Association 13 years ago when it published a Biomass Task Force Report that accurately predicted: “over time the fire-prone forests that were not thinned, burn in uncharacteristically destructive wildfires… …In the long term, leaving forests overgrown and prone to unnaturally destructive wildfires means there will be significantly less biomass on the ground, and more greenhouse gases in the atmosphere.”

Deadly Delay in Catching Up to Reality

California politicians, late to realize the true nature of the wildfire danger, have finally started to play catch-up. Last year, outgoing four-term Democratic Gov. Jerry Brown reversed his longtime reluctance to active forest management when he signed two bills into law, both of which passed on the last day of the legislative session in what was to become California’s deadliest wildfire year.

SB 901 allocated $190 million a year to use prescribed burns to reduce the fuel load while improving forest health, while SB 1260 made three important policy changes to streamline the ability to conduct prescribed and controlled burns; remove air quality impediments to preventive burns; and prevent environmental quality lawsuits from slowing or stopping needed burns.

Newsom’s more pragmatic approach to wildfires and forests was signaled during his 2018 campaign when he volunteered in an interview that California had “Hundreds of millions of dead trees” then noted that it cost his father $35,000 to clear “a small little patch of dead trees” on his property. While campaigning, Newsom called for improved wildfire surveillance and warning systems, better urban planning, and helping property owners clear brush. It looks like the legislature gave it to him, as he just signed 22 wildfire mitigation and prevention bills in the waning days of the 2019 legislative session.

Antipathy to Low-Cost Housing Makes Things Worse

In all likelihood, these measures will prove to be too little, too late for rural Californians, many of whom flocked to build along what is known as the Wildland-Urban Interface (WBI) where land was cheaper and housing costs far less than in California’s dense and heavily regulated urban centers.

The environmentalists who hold sway over much of the California political class chafe at these homes along the edge of the forest and chaparral, calling for development restrictions and special fire taxes to discourage low-cost housing in rural areas and around the suburban periphery.

And now, as the result of forest mismanagement by both the federal government and California, many homeowners living out in the WBI can no longer obtain fire insurance. No fire insurance, no mortgage. No mortgage, no house. Today, it would also appear, no electricity as well.

In time, perhaps, these policies will force all but the wealthiest of Californians to live in cities, crammed into tiny, energy-efficient cubes, leaving the forest to—once again—burn as it may.