It’s September 8, 2017, at 7:10 p.m., and the Boston Red Sox are taking the field against the Tampa Bay Rays. The atmosphere is relaxed. It’s a home game, and the Sox are leading the American League East, coming into this series off a two-game win streak. But nothing is over until it’s over, and it’s only the top of the first.

Four levels above the on-field action, Josh Kantor, the park’s organist, has his own challenge to deal with. He’s trying to learn the theme song from Game of Thrones. “Somebody wanted to hear it,” he explains, his fingers working. “It’ll be a little bit of an adventure in about 40 seconds.”

The 40 seconds pass. “Drop It Like It’s Hot,” the DJ’s latest pick, fades out. Kantor’s organ cranks up, and Fenway Park transforms, briefly, into a land of war and dragons.

By the song’s end, there are two outs on the board. “That was pretty good!” I say. Kantor nods: “Passable.” In the stands, someone, somewhere, is smiling at his phone.

Everyone knows what a baseball game is like. There are the sights: bright green grass, striped ump shirts, bases that look tiny from the cheap seats. There are the tastes and smells—hot dogs, popcorn, sweat—and that pleasantly crushed feeling that comes with being taken out with the crowd. And there are the sounds: the crack of the bat, the rolling applause, and the wheezy, cheerful organ, which soars over everything like a solid double.

At first glance, it may seem like hardly anything about the experience of a professional baseball game changed in the last century. But a trip to any modern ballpark offers a number of examples of how America’s pastime has evolved to face the future, whether it’s with big data or live fish. Thanks to musicians such as Josh Kantor, who use technology to find new possibilities in old-school entertainment, the organ is catching up, too.

This is baseball, so let’s get our stats straight at the outset. Kantor is 44 years old, and has been Fenway Park’s official organist since 2003. In his nearly 15 seasons with the Red Sox, he has missed exactly zero home games, which means that as of the end of September 8, he had been present for 1,239. During this time frame, the team’s home game win percentage has been a respectable .594, something Kantor occasionally, and half-jokingly, reminds Internet haters.

When there’s a full house—which has happened fairly often since he started—Kantor is playing for 38,000 people, nearly twice as many as fit into the city’s next-largest music venue. You can hear him everywhere in the park, from the press box to the top of the Green Monster. But if you want to see him, you have to ride a few flights of escalators up to what he describes as his “non-glamorous perch” within the State Street Pavilion Club.

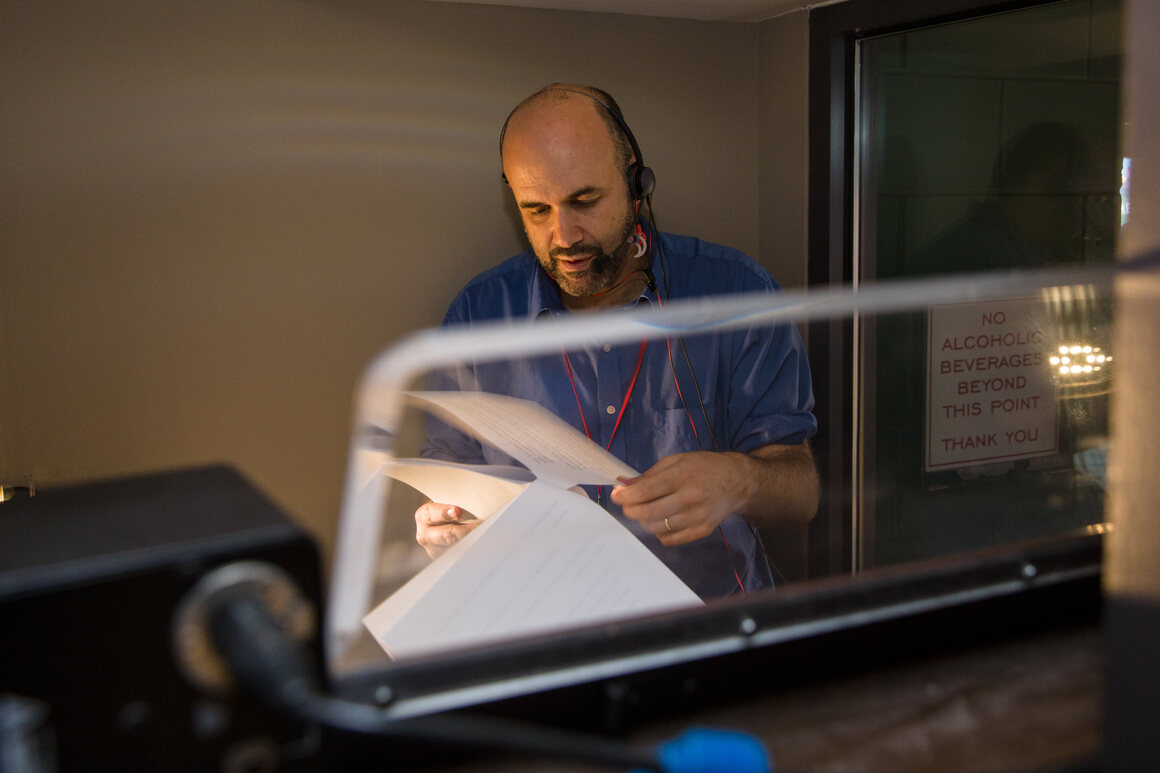

The club itself is ritzy—you can’t get in without a special season ticket—and it would be easy to mistake Kantor for a weird sort of hidden piano man, another amenity for exclusive guests. But a closer look reveals a larger operation. To Kantor’s right is his Macbook, opened on the padded piano bench, and a long-necked flexible lamp. To his left, there’s a window with a decent view of the first base line, and a briefcase-sized television, off for now. He’ll turn it on once the game starts, along with the red LED clock above it, which counts down the time left in the commercial breaks. Another huge screen—hung on the wall to his right, for the benefit of the Pavilion Club’s diners—is already going.

He’s wearing gray slacks, a blue button-down with the sleeves rolled up, a black headset microphone, and a pair of red earbuds that join just under his stubbled chin. (There’s another mic, fuzzy-headed, jutting out from the smaller television.) His cell phone is sitting on top of the organ, along with a small digital watch, which he’s placed face-up on the console, almost like a finishing touch.

The whole thing looks less like a traditional musician’s lair and more like an air traffic control booth, and in a way, it is: Kantor is constantly conversing with an entire production staff, which works together to keep the park’s audio well-oiled. “I’ve got eight conversations in this ear,” he says. “I’ve got the organ in this ear. I’ve got an extra earbud for figuring out songs. You learn what you can tune out.”’

Baseball organs aren’t quite as old as baseball. They’ve been a part of the sport since April 26, 1941, when Chicago’s Wrigley Field brought in a musician named Roy Nelson to entertain fans. He played a lot of then-popular music, but had to stop half an hour before a game actually began. (As the Chicago Tribune explained at the time, “his repertoire includes many restricted ASCAP arias, which would have been picked up by the radio microphones,” breaking copyright law.) Despite rave reviews—Sporting News praised his “restful, dulcet” playing—Nelson’s career lasted only two games. The next time the Cubs were out of town, stadium management quietly removed his organ.

Kantor is also generally not broadcast, for the same rights-related reasons. It’s a restriction that, paradoxically, gives him an enormous amount of freedom. He can play whatever he wants. His own favorite organist is Nancy Faust, who played for the White Sox from 1970 through 2010, and became famous for her clever song choices. If two people were running bases, she might treat the crowd to the Mario Bros. theme. Kantor approaches his soundtracking in a similar spirit, with a few twists of his own. “Happy 76th anniversary of MLB organ music,” he tweeted this April 26. “I’m sure Ray Nelson (1st MLB organist) would approve of the Flo Rida jams I’m busting out tonight.”

It also means that listening to him play is exclusively a live experience, a rarity in this time of cell phone cameras and instant concert recordings. At exactly 5:40 p.m., 90 minutes before the action starts, Kantor starts running through his own kind of warmup, a 35-minute medley meant to entertain the pre-game guests. To a rookie like me, the Pavilion Club offers near-endless distractions: soft puffs of air from the swinging restroom doors; the clatter of dropped forks; the smell of spicy fries, which comes in waves. Feet from us, a table full of businessmen loudly compare appetizers. Every once in a while, through the window, a ball arcs in and out of view. Outside, the players are warming up too.

Kantor, unfazed, moves seamlessly through decades and genres, trimming the fat from songs and stringing them together like Fenway Franks. He brings “Come On Eileen” straight from the first chorus into the slowed-down, catchy bridge, then moves into something classic-sounding that I can’t quite put my finger on. Around the sixth song, the guy checking tickets at the Pavilion’s back door comes over, leans against the wall, and listens.

Kantor plays a Yamaha Electone AR-100, which he’s had since 2005. (After the 2004 Red Sox shocked everyone by winning the World Series, the organ company that had rented out the instrument to the park took it back, as it was clearly touched by magic.) Of all the technology in an organ booth, the axe itself is the most important, and Kantor has customized his for flexibility and nostalgia alike.

Programmed presets in the keys let him quickly ape all kinds of contemporary rhythms, from reggaeton to post-punk. At the same time, the instrument’s robust, zippy tone is meant to emulate that of Boston legend John Kiley, who manned Fenway’s organ for 36 years, beginning in 1953. “I like the idea of having the people who came here a generation or two ago recognize it,” Kantor says.

The sound proves surprisingly versatile. As the preshow continues, Kantor adds his name to the long list of musicians who have interpreted the jazz standard “All of Me,” then to the slightly shorter list of people who have covered Squeeze’s “Tempted.” At one point, he throws in some Gin Blossoms. Kantor plays by ear, and all the songs are chosen pretty much on the spot, based solely on the various vibes available: the stakes of the game, the mood in the park, the weather. “It’s just whatever’s in my head,” he says.

Around 6:15 p.m., he begins the last chorus of his last song—another just-elusive chestnut—and hops on the microphone to inform TJ Connelly, the park’s DJ and music director, that it’s his turn. “Wrapping up,” he says. When the blast of recorded music takes over, it seems overstuffed.

Connelly is Kantor’s closest collaborator. They’ve soundtracked Fenway together for well over a decade, and they’re in constant communication, from their traditional pre-game check-in all the way through the last notes of the exit music. “We’re almost like an old married couple at this point,” Kantor says, flicking on his earpiece. He updates Connelly, practically giggling: “We’re talking about you! Maybe your ears are burning.”

Connelly works on the park’s Media Level, which is one floor above Kantor’s booth, and after the pre-show medley is over, we go up to meet him. He’s shaggy and tall, the Hobbes to Kantor’s Calvin. Connelly is a music geek too—he has a radio show, and also DJs for the Patriots—and it quickly becomes clear that for both he and Kantor, part of the fun of the job is trying to outdo the vast jukebox in the head of the other.

They’ve devised various challenges to accomplish this. “Sometimes, he plays a song, and I’ll play a song it reminds me of,” Kantor says. “We also do theme nights.” Earlier this year, when members of the ‘67 pennant-winning team were in attendance, they only played songs from 1967. On July 20, the anniversary of the first moon landing, they always stick to songs about space. “Fans will get into it, too,” Connelly says, if they notice. When the April 21 game became an impromptu Prince tribute, it made national news.

Still, it’s clear these meta-games are mostly for them. The two give off a palpable conspiratorial energy. As they go over the few times they’ve shamed themselves by accidentally repeating a song during a game, an older man pipes up from across the room, to share his fondness for “Mr. Sandman.”

“Oh yeah,” Kantor replies. “I played that yesterday, when they were putting new dirt on the pitcher’s mound.” Immediately, as though he can’t help himself, Connelly offers up his own suggestions. “Fixing a Hole,” he murmurs. “Concrete and Clay.”

By 7 p.m., Kantor is back on the fourth level, in ready position. His hands hover over the keys. It’s the pregame show, and everyone the announcer names—the night’s various honored guests, the members of the starting lineup—gets a little introductory “dun dunnnn,” like a steamboat whistle. Extra attention must be paid in case something unexpected happens, as it did a few weeks ago, when the ceremonial first pitch hit a bystander dead in the crotch. (Kantor was ready, and punctuated the moment with what Esquire called “a jaunty riff.”)

But most of the time, the real fun starts with the first inning. If you want to talk to Josh Kantor during a game, and you’re not on the other end of any of his microphones, your best bet by far is Twitter. Kantor takes requests at @jtkantor, and here, too, his particular talents get a workout. If he knows your song, he’ll almost definitely play it. (Exceptions include overly happy songs during a losing game, or “Don’t Stop Believin’,” which is reserved for the playoffs.) If he doesn’t know it, and he wants to, he’ll find it on Youtube, and practice until he’s got it down. Learning a new song usually takes him no more than a few minutes.

Kantor started soliciting requests on Twitter six years ago, at Connelly’s suggestion. (Connelly does the same thing, at @senatorjohn.) He now gets between 3 and 20 asks a night, and does his best to accomodate the good ones. Like most professionals, his work habits have been somewhat upended by this particular technology. He still logs all the new songs he learns in his huge paper notebook, but his dreams of organizing it are slowly fading. “If I’m just going to learn requests all night, why bother having a database?” he asks. Some of his game-time priorities have shifted too. “Before Twitter, I watched every pitch,” he says. Sometimes he even filled out a paper scoresheet. Those days are gone.

But even as he’s paid slightly less attention to the games, he’s been able to spend a lot more time getting to know his audience. Management has moved Kantor and his organ around a lot over the years, between rooms and floors, he says. Up in the Pavilion Club, he’s become kind of a Fenway Easter egg, like the rooftop garden or the red Ted Williams seat—fun to stumble on, but not an obvious destination.

Over the course of this Friday night game, just three sets of fans come by to visit on purpose: a dad trailing two kids, a group of older women who yell “We were wondering where you were!,” and a large drunk man who stops briefly to dance outside the window. “This happens the majority of the nights,” Kantor says, when the man leaves. It is, he says, a bit off-putting. “Sometimes you feel like an animal in a zoo. People are just watching you and you can’t talk to them.”

Virtually, though, a whole stream of fans is now poking their heads in, saying hello, getting comfortable, and chatting about music. “Someone just asked for Robyn!” Kantor says, grinning, around 7:30 p.m. “I haven’t played her in years.” He quickly unspools a flawless “Show Me Love.” As the innings slide by, and the Sox rack up runs, Kantor keeps fielding requests. “Paint it Black” by the Rolling Stones. “Dynabeat” by Jain. Britney Spears’s “Toxic,” which also requires a quick study session, and which he hums on and off for the rest of the night.

Kantor is far from the first baseball organist to take requests. That honor also goes to Nelson: after he debuted in 1941, the Chicago Tribune suggested mailing him suggestions for “any little number you’d like to have rippled off some afternoon.” He’s also not the first to do so over Twitter. That would be the Atlanta Braves’ Matthew Kaminski, who’s known for concocting esoteric musical puns from players’ names.

Half of North America’s 30 major league ballparks currently employ live organ players—a slight improvement from ten years ago—and Kantor attributes some of this resurgent interest in the organists’ improved accessibility. “There’s been a tiny bit of a renaissance,” Kantor says. “Some of us are embracing social media. There’s a bit more interest now than when I started in having live music be a part of ball games.”

What makes Kantor stand out from his peers is his remarkable enthusiasm. Here is an organist who once spent an entire morning soliciting suggestions for history’s worst hit song, replied to over 400 suggestions, polled based on the results, and played the winner that afternoon. (It was Billy Ray Cyrus’s “Achy Breaky Heart.”) Another time, he promised to play “Seven Nation Army” to dozens of requesters, and then rickrolled them.

He invites fans upstairs to see (and sometimes play) the organ. If someone compliments him, he takes the time to thank them. If he can’t get around to a request, he apologizes, with true regret. For this reason, every time the Red Sox social media manager suggests tweeting about him from the team’s 2 million-follower account, he demurs. “I’d get 200 requests a night,” he says. “I’d have to say no, and people would be disappointed.”

Each game, every baseball organist gets one guaranteed moment in the spotlight: the seventh-inning stretch. In the bottom of the sixth, a cameraman walks into the Pavilion Club, ready to go. Evan Longoria’s line drive lands in Dustin Pedroia’s glove, the Sox jog off the field, and the cameraman stands on a chair and points his lens straight at Kantor.

All at once, Kantor’s face appears on the Jumbotron, cheesin’. He mouths along with his own introduction (“sing along with Fenway Park organist Josh Kantor…”) and launches into “Take Me Out to the Ballgame,” for (at minimum) the 1,239th time in his life. As usual, 38,000 fans provide lusty vocals. This isn’t the same as busting out a Mountain Goats deep cut and blowing the minds of exactly five people, but it’s definitely another kind of good time.

Earlier in the night, I had tweeted a request at Kantor: Fleetwood Mac’s “Secondhand News,” my own attempt at being germane. A little later, I hear him bring Connelly up to speed on it—“I was thinking I might do it for the mid-seventh fill, if you’re cool with that”—and now it was go time. As he launched into the opening notes, I felt as though, standing in the middle of the crowd, I had snagged a foul ball.

By the bottom of the eighth, the Pavilion Club has mostly emptied out. Restaurant staff is sweeping up. The fans he’d invited upstairs can’t visit tonight, and so Kantor plays the crowd out, and then prepares to leave himself.

Earlier, the older guy on the media level—the one who professed his love for “Mr. Sandman”—had also offered his own take on the moon landing. “Do you think they really did it?” he asks. “I heard it was a soundstage.” Kantor—who respects the fans and the spectacle—answered like a true 21st-century magic-maker. “Either way,” he said, “they worked really hard on it.”