Salina, I’m as nowhere as I can be

Could you add some somewhere to me? — “Salina,” The Avett Brothers

“You’ve come to the worst series,” says JD Droddy, the 73-year-old manager of the independent league Salina Stockade, when I meet him in the last week of July at his team’s ostensible base of Salina, Kansas. From a spectator’s perspective, he’s probably right. In returning to its nominal home, his team has given up any glamour that its new level of professional baseball can boast.

Nine days earlier, the Stockade played a weekend series in St. Paul, Minnesota, at CHS Field, the recently constructed, almost big-league-looking home park of the St. Paul Saints, one of the best-attended teams in all of minor league or independent baseball. There, the crowds averaged 8,500, rivaling the largest single-game audiences that ever saw a Droddy-managed team in his three previous years as a manager. Now, he and I are almost alone an hour before first pitch at Salina’s 26-year-old Dean Evans Stadium, which usually hosts amateur games (high school, college, and American Legion). Our only companions are the stretching Stockade and their American Association opponents, the Wichita Wingnuts, whose bus has just pulled into the parking lot after a 90-mile ride north on I-135.

Ben Lindbergh

The series that Droddy describes as “the worst” will also be his last. After these three games in Salina, the grandfather and two-time previous retiree will re-re-retire and ride his RV into the sunset — or, more accurately, the total solar eclipse, which Droddy, an amateur astronomer, will watch in Casper, Wyoming, on August 21. Astronomy is one of several side projects for Droddy, a Vietnam veteran who left the Air Force as a lieutenant colonel after 20 years to get a law degree from Harvard (JD, JD) and become a commercial litigator, then worked as a graduate professor and school administrator at Western Kentucky University and Vermilion Community College, respectively, after tiring of practicing law — all before beginning his fourth career as a baseball manager in 2012. A professional playing career is a quasi-prerequisite for most managers, but Droddy, who considers his skippering self-taught, had never played above Little League or run a team at any level before a pastime turned into a passion and he backed into a managerial job in his late 60s. The former president of a musical theater company, he’s also a self-taught musician and playwright, and the five degrees he holds litter his résumé like stats on the back of a baseball card: BA, MBA, JD, MA, PhD. Seventy-three years doesn’t seem like enough time to have lived that much life.

On this day, Droddy isn’t strumming, stargazing, or studying case law. He’s trying to track down Wichita’s trainer, a staple of most teams that the Stockade don’t have. One of Droddy’s outfielders, Jonathan Moroney, collided with a wall and suffered possible concussion symptoms at the end of the team’s previous series against the Gary (Indiana) SouthShore RailCats, then convalesced during the 12-hour bus trip from Gary to Salina. The RailCats’ trainer had told Droddy that Moroney would need 25 hours without symptoms to be cleared to play, leaving his status uncertain. “He’s a kid that we’re doing those percussion protocols on,” Droddy says. He pauses. “Concussion, not percussion. I’m a musician.”

Ben Lindbergh

Droddy knows that the first-place Wingnuts have a trainer who’ll tend to his players, like an army medic who’s bound to triage and treat combatants on both sides. After he finds her, she examines Moroney and pronounces him fit to play, which makes Droddy happy even though it means he’ll have to rewrite his lineup card. Like a parent dispensing allowance, the trainer also hands Droddy an envelope from the league thick with meal money for his players, which makes him even happier. Whatever else they’re lacking, at least the Stockade won’t starve. But they’re lacking quite a lot.

The Stockade’s players, Droddy says, “maintain a tremendously positive attitude against the most daunting of obstacles that you can imagine.” For one thing, the team, which was born in a desperate, eleventh-hour attempt to prop up its league, lacks players with high-level professional pasts: As this series starts, the Stockade’s 23-man roster (the circuit’s standard size) contains 19 players who started the season as American Association rookies. They also lack a home that signifies more than one word on their jerseys: Their next three games are the last of only seven that they’ll play in Salina in their whole 100-game season, which lasts from mid-May to early September.

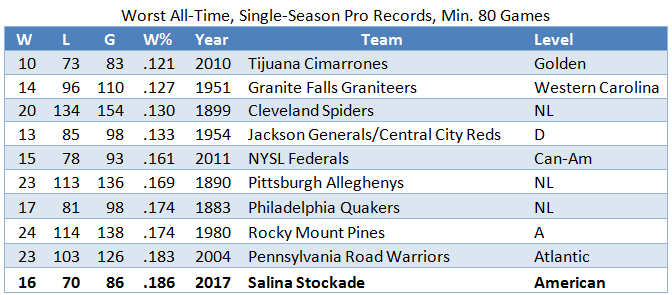

What they don’t lack is losses. After being swept by St. Paul and dropping three of four in Gary, their record stands at 10–55. That’s a .154 winning percentage, which puts them 27 games behind Wichita in the American Association’s South Division, in firm possession of the worst pro record at any level in 2017, and within slumping distance of the worst professional record of all time. (Their record has improved only slightly since then; the Stockade are now 16–70 and 36 back.)

Droddy wouldn’t want this story to dwell on Salina’s losses. Nor would he want it to highlight him. Although there’s no gaggle of writers waiting to talk to him in Salina, his distinctly un-baseball background has drawn reporters and even reality-TV producers who made him a central figure in a 2014 Fox Sports baseball series. But the Stockade’s saga stands on its own. “This whole thing is not about me,” Droddy says. “It’s about these young guys who have a dream to play professional baseball as high as they can get. And on this team especially, these are for the most part guys who nobody ever gave an opportunity to or they got released after not much of an opportunity, and they want to show that they can perform. And it’s a hell of a story that people are ignoring. And it drives me crazy they want to talk about me because I can’t hold a job.”

The Stockade have next to no history, no fan base, no future, and no business being here, and are steered for most of their season by a retiring, renaissance-man manager who himself is always on the move. They’re way out of their league. They know it. And they don’t give a damn.

The call that created the Stockade came on May 3. Miles Wolff, the commissioner of the American Association of Independent Professional Baseball, needed a new baseball team, and he hoped that Andrew Dunn, the commissioner of the Pecos League of Professional Baseball Clubs, could supply one. The catch: Opening Day in the American Association was scheduled for May 18.

“A league does not want an odd number of teams,” Wolff, the founder and former president of Baseball America (as well as the current or former commissioner of multiple indy leagues), says via email. “With games scheduled every day, it would cause too many off days.”

Yet the American Association, normally 12 teams deep, was down to 11, because the Laredo Lemurs (formerly the Shreveport-Bossier Captains) had dropped out in early May after a decade in the league, amid a battle between the team’s owner and the city. That dispute doomed the Lemurs and left the league looking for a franchise to pinch hit for a year until a permanent replacement could be found.

Wolff had already talked to Dunn during a previous scheduling crisis about possibly providing a team if one was ever needed, so he knew where to turn. “Andrew could do it at less cost than if the league decided to furnish its own road team,” Wolff says. “He also had available players.”

To understand why Dunn would scramble to send talent to another league, you have to understand the structure of indy ball, a multilevel outpost of professional baseball that exists separately from but in parallel to the farm systems affiliated with major league teams. Indy ball players are paid to play, although most of them make less than affiliated minor leaguers, who themselves earn so little that their salaries have spawned multiple lawsuits against Major League Baseball. Many indy leaguers are former and/or future members of major league organizations. Some big leaguers — including Kevin Millar, David Peralta, Chris Colabello, and Daniel Nava — first established themselves in the indy leagues, and many others (including Rich Hill) have done stints there while working their way back from injury or ineffectiveness. It’s not as sexy or high-status as affiliated ball — many indy teams rely on host families to put up their players — and it’s often a dead end, but it’s the best option for players who have gone undrafted or been released by a big league team but aren’t ready to retire.

Indy ball has a hierarchy, just like affiliated ball’s Triple-A, Double-A, and A ball. On the more amorphous indy side, which currently comprises six established circuits and 54 teams (plus some small, upstart leagues that regularly pop up on the periphery and vanish again), the talent ranking runs from the Atlantic League at the top to the comparatively sparsely attended and underfunded Pecos League at the bottom.

According to Baseball Prospectus cofounder Clay Davenport’s calculations this spring of global league strength — which were based on the performance changes of players who moved between indy ball and affiliated, and vice versa — the Pecos League (established in 2011) is the world’s lowest-level professional circuit, with a strength rating of .245 (compared to the National League’s and American League’s 1.000 and 1.107, respectively). The American Association checked in at .587, which puts it on par with High-A leagues and means that the quality of competition is more than twice that of the Pecos League. In recent years, the American Association (established in 2005) has sent the second-most players to affiliated ball, trailing only the Atlantic League. And at least a dozen players with big league experience have appeared in the American Association this season, including Tony Campana, Reggie Abercrombie, Caleb Thielbar, and James Russell.

The affiliated-ball analogue of jumping from the Pecos League to the American Association would be going from the Pioneer League (short-season class A) to the Pacific Coast League (Triple-A). That’s the sort of leap that typically takes years for players to make, if they overcome the steep odds against their climbing that high at all. Crossing that gulf in a single season would almost never happen. But something comparable has happened in Salina, like a natural experiment designed to expose how huge the gradations of excellence are even within the sliver of talent at the far right of the baseball bell curve.

The goal of any indy league, aside from putting together enough pennies to stay in operation and entertaining local communities, is to help its players pursue their dreams by advancing to the next level — which in turn helps the lower-level league position itself to potential recruits as a means of climbing the ladder. It makes sense, then, why Dunn would find the prospect of placing a Pecos League–caliber team in the American Association appealing. “It has allowed 30 players over the course of a season and 16 players full time [to] play a full season in the American Association that would not have otherwise gotten the opportunity,” Dunn says via email. It makes equal sense, though, why that rapid ascent would put the Stockade at risk of destruction, like a deep-sea diver crippled by the bends after surfacing too soon.

Even after they’d agreed to solve each other’s problems — lack of exposure and an odd number of teams, respectively — Dunn and Wolff couldn’t simply promote the Stockade to the American Association, because the Stockade didn’t actually exist at the time.

Ben Lindbergh

Dunn had first formed a team called the Stockade in 2016, naming them after a fortified barrier that had protected the town not long after its founding in 1858. That incarnation of the Stockade, which was also created for scheduling purposes, had also been a traveling team that had only 10 dates in Salina because of conflicts at Dean Evans, but it had played in the Pecos League. In that environment, the Stockade finished the shorter Pecos League season 29–36, only the fourth-worst record in what was then a 10-team league. In February 2017, though, that team was disbanded, done in both by geographic isolation resulting from the folding of other nearby franchises and by the departure of a former Stockade coach who took most of the players from 2016 with him to a team in Garden City, Kansas, leaving many spurned Salina supporters unwilling to offer their services as host families again. The 2017 Stockade are an almost entirely different entity: Only a few players from the 2016 team have spent any time on the 2017 roster, and all of them were either early cuts or late additions this season.

So tenuous is the link between the two Stockade teams that the new club was almost called the Houston Apollos, a name Dunn has used for a team in the Pecos Spring League, an amateur, developmental league for players who are hoping to showcase their skills and get signed for the summer. “The reason we’re not the Houston Apollos is because we didn’t have enough hats, and we couldn’t get hats in time for the season,” Droddy says with an “only in indy ball” laugh. “As a last-minute deal, it takes time to get these hats made.”

Immediately after getting word from Wolff in May, Dunn called Droddy, with whom he’d worked before. In the Pecos League’s inaugural season, Droddy, who was then living in New Mexico, had volunteered to host three players. He grew more involved, serving as the unofficial photographer for his host players’ team. The next year, a coach he’d befriended in 2011 became the manager of a newly formed team, the Trinidad (Colorado) Triggers, and asked Droddy to be his assistant, giving him his first official baseball coaching experience. The next year, Droddy took over the Triggers as manager and stayed on for 2014, before “retiring” in 2015 and spending a year away, during which he still served part time as the league adjudicator (a settler of disputes between parties in the Pecos League). In 2016, Dunn lured him out of retirement to manage another new team, the Tucson Saguaros. The Saguaros won the Pecos League championship, which would have been a career-capping accomplishment for Droddy. But this spring, Dunn persuaded him to sign on as Salina’s manager, appealing to his loyalty to the Pecos League and the players for whom this could be a big break. It wasn’t a tough sell.

“I’m 73 years old, I shouldn’t be doing this,” says Droddy, who’s being paid $10,000 total to be back in the workforce. “[My motivation] is the players. … My objective is to get as many guys promoted as I can.” Droddy’s wife of 34 years, Judy, also agreed to the assignment, knowing how much it meant to her husband, even though it meant that she’d be without him for most of the summer at the couple’s home in Colorado Springs. Droddy’s only condition was that he be allowed to walk away after this series to honor family (and eclipse) commitments in August, which is why Dan Aldrich, once a 22-year-old Yankees minor leaguer and now a banged-up 26-year-old Stockade outfielder, will be retiring as a player to take over the team after this three-game set. Aldrich amassed an unreal .370/.448/.752 slash line with 56 homers in 150 games in the high-offense Pecos League from 2014 to 2016, but even that wasn’t enough to intrigue another team in affiliated ball. With the Stockade, he’ll finish with a .241/.258/.399 line.

If Dunn and Droddy had no time to wait for hats, they had even less time to figure out which heads would be wearing them. “He and I worked together, and we each had a veto,” Droddy says. “If he didn’t like him, or I didn’t like him, he didn’t call. We both like him, he can.” The pool of potential talent was shallow. By early May, the best 2016 Pecos League players had already been promoted to higher leagues, and the duo elected not to raid Pecos League rosters and cannibalize other clubs on the eve of the season.

Contrasting approaches to player evaluation further complicated the recruiting. Dunn, Droddy says, is an “emotional” talent scout who falls head over heels for every player he likes. “I’m a numbers guy,” Droddy says. “If you want to play for me, don’t send me a video. I won’t look at it. I don’t care what your video looks like. If you didn’t look good, you wouldn’t send me the video.” (Droddy praises strikeout-to-walk ratio and rails against the misleading nature of ERA, although he spoils his incipient stathead image when he refers to “WAR crap” as “nonsense.”) The pair picked up one player at a tryout and signed 16 more former (and, if not for the Stockade, probably future) Pecos League players who were still weighing their options with other teams, which made up the bulk of the Opening Day roster. Most of those signees had previously played for or against Droddy, so he “had some idea of who they were and what they could do,” but preparation for the season was still absurdly abbreviated. Spring training, if one can call it that, lasted two half days and one full day.

Ben Lindbergh

Dunn’s and Droddy’s recruiting calls were hamstrung by their budget as much as their timing. When the Lemurs folded, Wolff says, they forfeited the $200,000 letter of credit that all American Association teams are required to post. Most of that went to the Pecos League to cover the Stockade’s expenses, including travel and payroll; the American Association isn’t set up to pay the bills of individual clubs, so for reasons of expediency and liability, it was preferable for the Pecos League to handle the details, bankrolled by Salina’s new league. Each American Association team was required to pay for hotel and meal money when Salina came to town. Even so, the Stockade’s player payroll was restricted.

“It really wasn’t easy to get the players that we wanted because we were not allowed to pay league minimum,” Dunn says, referring to the American Association’s $800-per-month rookie minimum. “Players wanted to play in the American Association, but not for $400 a month and meal money. Players wanted $800-$1200.” Salina couldn’t even cover the cost of travel to and from the team, which is standard practice in the American Association.

Twenty of the 23 current Stockade players are imports from the Pecos League, and they’re no better off financially now than they were then, aside from the meal money and the better class of hotels. The poor quality of Pecos League road lodging comes across in the fervor with which Stockade closer Tyler Herr — a former Twins draftee and farmhand after whom Droddy has nicknamed the late innings “Tyler Time,” and whom he claims can throw 94–95 — raves about this season’s stays in Hyatts and Country Inns. Even so, “you’re not making money,” Herr says. “You’re pretty much still surviving and trying to just get through the season.” He lists visiting the Mall of America as the highlight of his 2017 season, but says he was too worried about money to buy anything while he was there.

As irregular and potentially detrimental as Salina’s circumstances are, the players’ similar origin stories have been a bond. “There’s a bunch of Pecos League guys, and we all … played each other in the championship or in different leagues, and then we all formed this one team,” Herr says. “We all had our war stories. … And it was just so cool to finally all be teammates after all these years of playing against each other. … Ever since day one we’ve gotten along. I mean, with this team, we kind of know our place.” The Stockade’s website is still sending mixed messages about what that place is, continuing to display the standings for the Pecos League, not the American Association. The players, though, are like a group of Wile E. Coyotes, defying gravity as long as no one points out the precariousness of their position. One need not suffer from impostor syndrome when one’s teammates are impostors too.

All of Droddy’s previous teams had at least qualified for the playoffs, but in light of the handicaps he faced in this case, neither he nor Dunn had any illusions about the outlook for the Stockade. “Andrew knew the talent level of the American Association and told us from the start that his team would win 10 to 15 games,” Wolff says. Pretty good guess.

I’ve arrived in Salina on a Sunday shortly after the American Association All-Star Game. The Stockade are the only team in the league without an All-Star representative, and a glance at their stats makes it hard to argue that they were snubbed.

In other ways, though, the team suffers constant slights that seem avoidable. If you visit the American Association website, you’ll see this banner at the top:

Count them: That’s 11 teams. Even though the Stockade bailed out the league, they don’t get equal billing with the rest of its members. They do have their own page on the website, but the URL is www.americanassociationbaseball.com/teams/laredo, another indignity. And while all of the players have pages on Baseball-Reference, many of them have question marks after their names, indicators of unknown handedness that seem to express a deeper doubt about whether they belong. The Stockade are second-class citizens even online.

And, I soon see, even in their supposed home park. The scoreboard accurately lists Salina on the top line, Wichita on the bottom: Somehow the Stockade are still the road team for this series in Salina. Consistent with the theme of this visit to Salina not being a happy homecoming, the team has been downgraded to a Motel 6 for this series. The next Hyatt will have to wait.

Ben Lindbergh

Salina is close to the center of the state at the center of the States. It’s also centrally located in the league; the American Association’s preexisting teams bisect the continent, running from Winnipeg in the north to Grand Prairie, Texas, in the south, with Gary in the east and El Paso in the west the most distant deviations in longitude. When Salina entered the league at the last minute, though, it was too late to redo the American Association’s schedule, so Salina inherited Laredo’s slate. Because they can’t play their home games in Laredo, they don’t have home games. This isn’t unheard of in indy ball, and this isn’t the first time that it’s had disastrous results — the 2011 NYSL Federals went 15–78 as a traveling team, although that was in the Canadian-American League, and not nearly so last-minute — but the Stockade are the first traveling team in American Association history. (“We don’t own white pants,” Droddy says.) Instead, they play in other teams’ parks at a near-permanent home-field disadvantage or, in case of conflicting events, as the perpetual visiting team in neutral parks, with attendance totals reminiscent of the crowdless game between the Orioles and White Sox in 2015. When I naively ask Droddy if any of those neutral-location games was scheduled in the interest of fairness, he snorts. “The league isn’t interested in fairness to us,” he says.

Droddy was raised in Hull, Texas, but more appropriately for the manager of an itinerant team, he was born in Call, Texas — a town, he says, that “does not exist anymore.” And befitting its status as the home of a baseball team that barely plays there, Salina largely owes its industry to businesses based in other places. The largest employer in the town of slightly fewer than 50,000 is Tony’s Pizza, a frozen-pizza manufacturer owned by a Minnesota-based parent company; the biggest acts that come to town play at Tony’s Pizza Events Center, where in 1990 Kiss’s stage set blew out the arena’s electricity, prematurely ending their show. The band has never been back.

Exide batteries and Philips Lighting have factories here, although one wouldn’t know it from the gloom in the outfield at Dean Evans Stadium when the sun goes down. Salina is an aviation hotspot (no help to the bus-bound Stockade) and also central Kansas’s hub for big-box stores. The area is huge on health services, too, the Stockade’s missing medical staff aside.

Although Wichita, the winner of six consecutive division titles, is the worst matchup the manager could have for his swan song, his spirits seem high. The Stockade’s record could scarcely be worse, but they aren’t the Washington Generals, the traveling team that exists solely to lose to the Harlem Globetrotters. “When you look at our record, you’ll say this team is not competitive,” Droddy says. “We’re not competitive to win the championship. But … when we go on the field, we’re very much a threat to win.”

Ben Lindbergh

Droddy cites “close to a dozen games” lost by one run, and “over two dozen” lost by three runs or fewer. His claims check out; at this point in the season, the Stockade have had 10 one-run losses and 25 by no more than three runs. Their Pythagorean record during my visit says they should have two more wins than they do (now up to three), which upgrades them from terrible to … well, still pretty terrible. “Every win is a highlight,” Droddy says, when I ask about the best of times for the Salina Stockade; it’s easy enough to recall all of them.

The worst of times was a series in late June, when Sioux Falls swept them by scores of 15–1, 15–1, and 11–4. Since then, though, the Stockade have added some Pecos League players whose teams didn’t qualify for the Pecos League playoffs, which has helped shore up some of their (with apologies to Droddy’s sentiments about WAR) sub-replacement-level positions. “For the most part, they’re a lot more competitive,” confirms Wichita radio broadcaster Rob Low. “Just looking at the scoreboard every night, it seems like they’re not getting killed as often.” That’s progress. Every player I talk to points to this improvement, possibly because Droddy makes sure that it’s always on their minds. “It’s been more important to reinforce the positive [this season],” he says. “With previous teams, there’s been plenty of positive that’s just been out there because we’ve been very successful.”

No one in the league wanted to play at Dean Evans Stadium. The Wingnuts are the only team that didn’t say that the stadium failed to meet American Association standards and outright refuse to come, and even with the first game about to begin, rumors are circulating that they’re still trying to find a way out of doing so for the rest of the series, despite a tournament taking place at their own park. The Stockade aren’t fond of Dean Evans, either. “We hate playing here,” Droddy says.

One indication of the stadium’s unworthiness comes when Salina lines up for the national anthem in front of the third-base dugout. Everyone has his hand over his heart, but no one knows where to look. “Where’s the flag?” says outfielder Roche Woodard. “I don’t know,” answers utility man Logan Trowbridge. Finally, it appears: an animated flag waving in a digital breeze on the TV-sized screen on the scoreboard, which will go dark for the rest of the game as soon as the song is over. Later, I find out that the rope on the flagpole broke a few weeks ago; someone from the city tried and failed to fix it, and will have to come back with a bucket truck.

Ben Lindbergh

The PA system sounds professional, but the opening strains of “Won’t Get Fooled Again” don’t have their usual adrenalizing effect when the stands are this empty. Tickets cost only $6, but I count 34 fans at the height of the crowd. I can clearly hear Low’s play-by-play in the press box from my spot in the front row — plenty of prime seats available! — and the cicadas outside are the stadium’s single loudest sound, except for the skritch of cleats on concrete when the clubhouse-less players trudge from their dugouts to the bathroom behind the grandstand. A heckler would have to be bold to drop verbal bombs here, because there’s no way to blend into a crowd or a stadium soundscape. The non-hecklers here today speak in hushed tones, wary of being overheard by the players, whose every utterance is audible.

After Salina fails to score in the first, Wichita ekes out a run with an infield hit, a walk, a double steal, and a sac fly. “Think we’ve already seen the winning run?” says a fatalistic onlooker. “I was thinking that,” answers his seatmate. Wichita scores twice more in the inning, capitalizing on a wild pitch, another walk, a third stolen base, and an error by the catcher, who throws the ball by the third baseman. Now we’ve seen the winning run. Wichita keeps tacking on and takes it 8–1, and Salina looks as sloppy as one would expect of a 10–55 — sorry, 10–56 — team, right down to the backstop sailing a between-innings warm-up throw into center field. At least the game is over in under three hours; the silver lining of losing so much and always being “away” is that the Stockade haven’t had to complete many ninth innings. At the Motel 6, a group viewing of a new Game of Thrones episode awaits.

The losing pitcher is 25-year-old lefty Troy Mannebach, who leaves after four innings, having allowed six runs (five earned) on eight hits, four walks, and one strikeout. He’s the only current Stockade player to have played for Salina last year, so I seek him out later to ask about the difference between the two teams. He’s clearly talked to reporters enough to speak in banalities, but not enough to learn to camouflage the clichés, although he does manage to sound sincere when he says it’s “a pretty cool experience to be a part of both original Stockade teams.”

Mannebach, who had never pitched professionally before last year, admits that he’s feeling the heat of the heightened competition. “The Pecos League, it’s like rookie ball,” he says. “But this American Association is some good stuff. It’s like two steps higher than the Pecos League, so it’s not easy playing up here.” His ERA is actually slightly lower than last year’s — albeit still over 5.00 — but unlike last season, he’s walked many more batters than he’s struck out, as Droddy, the ERA skeptic, is surely aware.

Diane Dowell

Mannebach acknowledges the low pay and long bus trips (15 hours from Sioux Falls to Cleburne, Texas, is the team’s record), but he says he enjoys being on the road, because that’s where the non-Pecos perks are — good-looking clubhouses, postgame spreads, two players to a hotel room instead of three or four. “They treat you like pro ball,” he says. He also invokes the siren song that sustains many a low-level employee: exposure. “I feel like I have a much better shot [of being seen],” he says. “You’re like, ‘Just have good numbers here,’ because it’s where you want to be, right? You’re only two steps away from the top.”

Herr, who’s played in low-level affiliated ball, seems less impressed by the American Association lifestyle. “Fast food is pretty much your friend around here,” he says. But he has the same attitude about the quality of competition. “I get to face the best of the best. Ex–big leaguers, ex-Double-A, Triple-A guys. All the managers get to see you, so if you’re doing well against them, you just never know what can happen for next year.” Droddy says that he knows for a fact that several of his players “have earned a lot of attention from the other managers.”

“Two steps away” is an optimistic spin on the American Association’s proximity to the limelight. And for most Stockade players, being seen just means that someone else will say no, bringing the player one step closer to the sickening acceptance that the yes isn’t coming. But because it’s extremely unlikely that any of these players is ever going to get the authentic MLB experience, an approximation, and some stories to tell, are the real rewards.

In the American Association, the illusion is much more convincing, and much less like a lower-res copy of a copy of a copy, than it is lower down. The crowds could pass for big league crowds if you don’t look up and notice that missing second deck. There are radar guns in the stands, held in scouts’ hands. Occasionally, the opposing hitter has service time. And if you find that you’re losing a lot — well, in any given game, big leaguers lose, too. It’s easier to suspend disbelief as long as you’re outside of Salina. And even there, you can close your eyes and try to talk yourself into the cicadas sounding like the roar of a crowd.

It rains the next day, too hard to play, so the second and third games against Wichita are squished and reconstituted into a Tuesday doubleheader of two time-saving seven-inning games. On this unscheduled off day, Droddy drops by my hotel, which marks the first time I’ve brought a reality-TV star back to my room.

Droddy is a “star” only in the sense that anyone who has ever appeared on a reality show is. Droddy’s Trinidad team was the subject of a six-episode series, The Pecos League, which was filmed by Fox Sports in 2013 and aired in 2014. It’s a decent anthropological look at life at that level, but Droddy is still displeased with the result, which he says, with some scorn, “got done back in Hollywood after the thing was over.” He estimates that the crew shot at least a thousand hours of footage, but says that “they edited out so much of the good stuff that would have made a good baseball story. They didn’t want a baseball story. They wanted a train-wreck story.”

Droddy didn’t give them one, shepherding his team to the playoffs. The series is still on iTunes, and some people other than writers doing Droddy articles are probably still stumbling across it; he claims that people who watched the show come up and ask to take pictures with him “all the time.” I haven’t witnessed this, but then again, I’m discovering that Stockade games in Salina aren’t the best places to people-watch.

Even amid the reality show’s fabricated drama, Droddy’s care for his players comes through. “He really understands the player’s aspect of it,” says Aldrich, Droddy’s designated successor. “He’s a good player’s coach.” Without knowing his history, it’s something of a mystery how Droddy manages to transcend his lack of playing experience and the big age gap between him and his charges, even as he needles them about rap rotting their brains in a stereotypically old-white-guy way. But the career chrysalises he’s shed have prepared him for his final role. “I’m much better equipped to deal with 20-year-olds than a lot of people, because I spent lots of years dealing with 20-year-olds in the Air Force, and as a college professor and college administrator,” he says.

Droddy’s baseball education began before he started racking up careers and degrees. Ted Williams’s exploits got him into the game as an only child, and he remains a Red Sox fan, even though he mostly watches Rockies games on local TV now, plus any national games he can catch. In the offseason, he has time to watch at least one MLB game a day. “Being elderly helps,” he says.

Droddy’s father was a barber who abused alcohol and abandoned the family when Droddy was in second grade, then died at 55 from cirrhosis of the liver. “I always said he was a great role model for me,” Droddy says. “He was a negative role model. … Lying in his coffin, he looked like a skeleton. You’ve heard the expression, ‘skin and bones.’ That’s literally what he was. He just had a skeleton with a little skin over it. And he wasted his life.” Droddy’s lifelong restless learning is the furthest thing from that. “I get interested in something, and I’d like to try it,” he explains.

Diane Dowell

Droddy followed in the Air Force footsteps of a much-admired uncle; another uncle was in the Army, but while many of Droddy’s relatives had been enlisted, he wanted to be his family’s first officer. In Vietnam, he flew 44 combat missions in a B-52 bomber as the electronic warfare officer, whose job was to “make sure we didn’t get shot down.” Eventually, he got grounded because of a back injury — which, he’s embarrassed to admit, occurred when a chair slipped while he was talking on the phone. A broken vertebra and a bone spur made it painful for him to sit through 12-to-13-hour missions, so the Air Force made him take on non-flying roles. Eventually, he left the service, having attained the rank of lieutenant colonel. Several decades later, he’s sitting on buses, not bombers, for 12 to 13 hours, and his back still bothers him.

Droddy plans the Stockade’s constant trips like they’re military campaigns, which makes him the perfect leader for a perpetually traveling team. “From the pure management standpoint, organization is a big logistics challenge for what we do,” he says. Sometimes, the team travels by bus; at other times, it takes three team vans, or forms a convoy with a bus, the three vans, and player-owned cars. “You can’t just say, ‘OK, I’ll meet you there,’ because you need to all arrive safely,” Droddy says. “You need to all arrive at the exact same time. So you have to organize a caravan. Not everybody knows how to do that. I have strict caravan rules.” Droddy makes sure that the oldest, slowest van is positioned between the two newer and swifter ones. “And for most of those trips, I rode in one of the vans,” he says. “We have two-way radios, and we make sure everybody gets to the red light.” Try to imagine any of that being part of Brad Ausmus’s job.

Maybe because his mind is so busy fine-tuning the things he can control, Droddy has mastered the art of not worrying about things that aren’t worth the energy. In the Air Force, he says, he was confident that his bomber wouldn’t be shot down. There were only three things that could kill a B-52: anti-aircraft fire, surface-to-air missiles, and Russian MiG fighters. The bombers could fly higher than all but one kind of anti-aircraft gun could shoot, so he scratched that threat off the list. The missiles didn’t scare him because he could blind their radars. His fellow crew members feared MiGs the most, but he was confident that his countermeasures could defeat their missiles. The only real risk, he thought, was being machine gunned from behind, and even then, he wasn’t worried: The B-52’s tail gun had the same range as the MiG’s front-facing gun, but the bomber would be flying away from the bullets while the MiG flew toward the B-52’s, which made the B-52’s effective range much farther. In retrospect, it seems as if Droddy was right. “A MiG never shot down a B-52,” he says. “A B-52 shot down two MiGs.”

These days, it’s fretting about umpires that Droddy can’t stand: There’s nothing he can do to prevent a bad call, and stewing over one will only make another more likely. Nor is there much he can do to make the Stockade lose less often; in baseball, managing is often an exercise in surrendering control. Droddy always wants to win, but he says he’s never agonized over Salina’s record, as long as he feels that the team played to its potential. Tomorrow’s second game, though, means more to him than most. “I’ll just be honest with you: I would like to win that last game. But if we don’t, then I’m not going to go home and lose sleep over it. I’ll go home and lose sleep if we don’t play competitively.”

At least the games won’t go nine innings, which should favor Salina. Randomness makes upsets more likely, and when you’re one of the worst pro teams in history relative to your league, small samples are your friend.

Attendance at Game 1 of the series-ending doubleheader sits at three at first pitch and peaks at nine, excluding me but including the guy with the white shirt that says “I’m proud to be one of Hillary’s deplorables” on the back in very bold lettering. With the din of 20-ish fans subtracted from Sunday’s already-slight crowd, I can hear every strand of the brush that the home-plate umpire uses to sweep off the plate, and the cooing of the swallow roosting in the rafters sounds deafening and rude.

Ben Lindbergh

After a scoreless first, Salina explodes in the second — in a good way, for once — as Wichita looks like the cobbled-together club raised up from a lower level. The Stockade start the inning with three consecutive singles, scoring one run, and the Wingnuts hold them there for the first out, a fielder’s choice. But the clear-headed Moroney singles, plating two, and Wichita commits errors on three consecutive batters, which allows another run to come around. The Stockade are up 4–0, and Droddy’s final-day dream is alive.

It lasts for roughly 15 more minutes. The Wingnuts send 11 men to the plate on six hits, a walk, and a hit by pitch, with the big blow a three-run, bases-loaded double by center fielder Tyler Sullivan. At the end of the inning, it’s 6–4 Wichita. Salina doesn’t score again, but its opponents add three extra runs regardless on the only home run of the series, which lands over the right-center-field fence, just to the side of the only hill I’ve encountered in Kansas. “NUTS,” Wichita’s jerseys say, and so do the Stockades’ faces.

Diane Dowell

Droddy spends the short time between games alone on the bench at the far end of the dugout, looking like he’s thinking long thoughts. Later, I ask him what they were. “It’s a sad moment, but it’s what I signed up for,” he says. “It’s sad not only because I didn’t finish [the season] with these guys, but because it’s the last game I’ll ever manage.”

I ask him what he’ll miss about managing. “I really enjoy the games,” he says. “But I’ll miss dealing with the players. That’s the reason I’ve unretired two or three times, in part, because I do miss it. But I’m going to continue to miss it after this. This is it. No more.”

I’ll spoil the suspense about Droddy’s last stand: There is no suspense. If there were footage from his final game, which roughly 38 fans watch, even the Fox Sports studio couldn’t make it more riveting. Salina loses 5–0, coughing up two in the second and watching the deficit widen by three in the fourth From there, the scoring stops and the last outs ebb away, long after the last hope has in my mind.

Ben Lindbergh

But not in the minds of the Salina Stockade. To their last strike, they’re up in the dugout, issuing attaboys. The chatter doesn’t alter the outcome, but it might make all the difference to Droddy. “Our backs have been against the wall this whole season,” Herr says. “It’s been really tough, but just because we’ve had a good group of guys, [we] were able to survive the season. If you had character flaws on the team, man, you would dread it, not want to be here.” And Aldrich, who’s about to inherit the team, says, “The travel situation, it’s unbelievable, man. Grueling life. We’ve had so much against us, all season long. … It’s definitely brought us together, I would say, in a good way.”

The PA plays the “game over” music from Super Mario Bros., and another Droddy career comes to a close.

“So is this the first year for the Salina Stockade?” one spectator asks another during Droddy’s last game. “I didn’t know anything about them. Some guy said, ‘I’m going to see the Wingnuts play the Salina Stockade.’ I’m like, ‘Salina Stockade? I thought that restaurant closed.’”

“No, that’s Sirloin Stockade,” the person next to him says. “Close.” It’s not a ringing endorsement of the mark the Stockade have made on the town.

Don Weiser, president and CEO of the Salina Chamber of Commerce, tells me, “We want them back, there’s no doubt about it.” But if no one goes to see Salina play, who, exactly, would “we” be?

“I don’t think Salina’s gotten behind [the Stockade],” says Michelle McWhorter, who minds the small concessions table at Dean Evans Stadium while her even smaller baseball-obsessed son, Jeremiah, chases foul balls. McWhorter’s family gets the goods themselves from Sam’s Club, so options are limited: water, Gatorade, Blow Pops and Tootsie Pops, fruit snacks, and beer that I hear secondhand isn’t fresh. There’s also a Stockade cap on sale for $25. (I don’t see any sales.) She estimates that she took in only $350 on Sunday, tickets included. She makes much more at American Legion games, where the crowds reach triple digits.

Taylor Deutscher, who served as the Stockade’s official statistician in 2016, is also at the game. I ask her how many Salina residents she thinks are aware that their town has a professional baseball team. She laughs, says, “Not many,” and launches into a story. “Last year, before the season started, the two [coaches] wanted to do a meet-and-greet for the community, and the team was supposed to be there,” she says. “It was on a Saturday, say from three to five or so. And I show up at four, and nobody’s there. Like, not even the team. So I contacted them, and they’re like, ‘Oh yeah, nobody came, so we kind of just left. We didn’t advertise it, so nobody knew about it.’ Like, that was probably your first problem, guys.”

Ben Lindbergh

The real problem, though, was probably being an indy ball team with few home dates and little money for marketing. Financially speaking, both incarnations of the Stockade were dealt an unwinnable hand. And consequently, they won’t be back in Salina.

“The only reason the team would be back is if the American Association needed a travel team, and if they needed a travel team,” Dunn says. Barring another last-minute dropout, that won’t be the case; the league has already admitted a new 2018 team, the Chicago Dogs, who’ll play in the Chicago suburb of Rosemont. Nor is there an obvious vacancy at a lower level. “I do not believe the Stockade will be back in the Pecos League,” Dunn says. “The attendance at American Association games was very, very low.”

In the first few minutes of his latest (and possibly last) retirement, Droddy gathers his team in front of the dugout. It takes him just 30 seconds to say his goodbyes, which conclude with, “You guys did great. I’ve enjoyed every minute.” He turns to leave, but Trowbridge stops him. “I just want to say, we appreciate everything you did,” the slick defender says. “I know a lot of coaches in the Pecos League are real unorganized and don’t go about things the right way, but I think you definitely did, so I appreciate that, JD.” Droddy thanks him, everyone applauds, and again Droddy tries to leave. Again he’s prevented from walking away. Everyone wants a handshake.

I walk Droddy to his car when he’s finally free, although he keeps collecting back pats. “You guys win some ballgames,” he tells one player who stops him. “Thanks for joining our ragtag outfit,” he says to another. And to me, he confides, “I’m probably going to sleep till noon tomorrow. I haven’t slept in in a long time.” That must mean he thinks the Stockade played competitively in their last loss with him at the helm. But I wonder whether he will sleep in, or whether the telescope, guitar, Native American flute, or keyboard will call him.

Ben Lindbergh

The Stockade will play on for a couple more weeks. “Nothing is given to us right now, and we’re pretty much at the very bottom, and we’ve just got to keep fighting and fighting and fighting to try to at least get seen or picked up for next season,” says Herr. “It’s pretty much a showcase every time we go out there, to try to win for the team, and also for your career.”

So far, the Stockade are a relatively respectable 6–15 in the Aldrich era, their incremental improvement a product of their reinforcements and resilience. Their cumulative record is 16–70, and they’ve been outscored by 3.2 runs per game, with both the worst offense and by far the worst pitching staff in the league. They’re a dead team walking in every way, facing almost certain contraction, and as out of contention as a club can be. But they do have games to go before the final out. And as long as they’re alive, maybe someone will get seen.

Thanks to Hans Van Slooten of Baseball-Reference for research assistance and to the Pavlovich family (Dane, Amy Kay, Atticus, and Sebastian), Jon Kaleugher, and Diane Dowell for their Kansas hospitality.