‘Til Death Do Us Part: The Longest Relationship in Baseball – Hardball Times

MLB’s broadcast booths don’t have that much turnover. (via Marianne O’Leary)

It’s 11 o’clock at night, Central time, and Brandon Liebhaber is still at the ballpark in Jackson, Tenn. He’s not taking extra fielding practice or discussing a new arm slot, though; he’s paging through stacks of press releases, coordinating interviews, and killing a forest’s worth of trees printing out packets of information for the coaches on situational stats for the upcoming series. The coaches have laptops of their own, but they’re old and finicky—the laptops, I mean—and the coaches don’t care to use them.

The team Liebhaber broadcasts for, the Jackson Generals, are currently enjoying one of their best seasons on record. They recently swept the Southern League end of season awards, and are headed to the playoffs. The team’s star, Tyler O’Neill, is a Triple Crown candidate and has won an impressive heap of accolades. At the moment, however, all of these things mostly just add up to more work for the 25-year-old Liebhaber, whose responsibilities include—but certainly aren’t limited to—booking hotel rooms for the team, handling media requests, putting together game notes for the broadcast, conducting interviews with players, printing out rosters and lineups, updating the team website and keeping the various Jackson Generals social media accounts well-stocked with informative, humorous content. If he remembers to eat, it’s a good day.

But that’s okay. Being busy keeps his mind off what happens when the summer ends, the gates of the ballpark at Jackson close, and once again he has to figure out an offseason plan that isn’t just a shrug emoji stretched over the winter months. Such is the life cycle of the minor league broadcaster. Liebhaber is Northwestern-educated, dynamic, witty and social media savvy. He is hoping to make enough in the offseason that he doesn’t have to move back in with his parents.

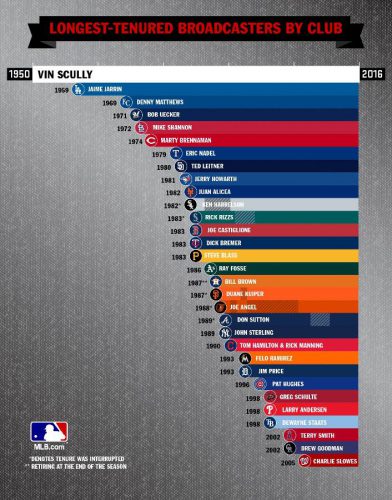

When Vin Scully called his final game for the Dodgers, it ended a 67-year career, the longest active broadcasting streak in major league baseball. This led Gemma Kaneko of Cut 4 to put together a list of the longest-tenured broadcasters for each team. Looking at the infographic (at right), one of the first things that jumps out is that the shortest tenure for any team is 11 years, with Charlie Slowes of the Washington Nationals, who took the helm in 2005, when the team was relocated. The other thing that becomes readily apparent is that the jobs slow to a trickle as the decades wend on. The ’80s saw 13 new broadcasters begin tenures; the ’90s, just eight. There are only three names on the list from 2000 on, and none in the past 10 years. Four of the people on the list have seen seven presidents since their first day on the job. Legendary Brewers broadcaster Bob Uecker has been in his role since before Disney World opened. Eric Nadel, in Texas, has been on the air longer than CNN.

When you type into Google “how do you become a sports…,” one of the top suggested results is “broadcaster.” But thanks to media outlets moving toward a less localized model, the number of general broadcasting jobs is on the decline, with a projected decrease of 14 percent over the next 10 years. Sports broadcasting, as shown by the Cut 4 article, is especially stagnant. What this leads to is a backlog of talented, educated, relatively youthful voices calling games that hardly anyone hears, their voices echoing through half-empty ballparks and across the still, quiet parts of small-town America. The minor leaguers whose careers they chronicle move on and move up, while they stay behind, in towns like Mobile and Modesto and Biloxi, waiting for a break that might not ever come.

Zack Bayrouty is one of those waiting on his next break. Heading into his 12th season as the broadcaster for the Stockton Ports—the High-A affiliate of the A’s—Bayrouty will spend the offseason broadcasting men’s college basketball for University of the Pacific, a job he’s happy to have. Broadcasting basketball, he says, is something he’d do even if he didn’t have to financially. “The fans are right on top of you and you can feel the energy in the building run through you,” he says. “That’s especially true when we go play at Gonzaga, or in front of 18,000 people at BYU. It’s a total rush and it’s so much fun.”

Baseball games are a different animal; the broadcast booth at a baseball game is removed from the field, high above the action, which unfolds more slowly than the non-stop, frenetic energy of a basketball game. While the basketball announcer is part of the crowd, the baseball announcer is more detached, adding to the solitary feel of the job.

Bayrouty recognizes that he’s lucky to have year-round work, and to have been with a team long enough to have established connections throughout the organization. “I consider myself so lucky to have worked with the A’s for 11 years,” he says.

“I’ve not only gotten to know the players and staff, I’ve gotten to really understand the organizational philosophies and appreciate the soul of the organization. That really helps enrich my broadcasts. I can also tell stories about A’s players who came through the organization over the past decade-plus. I can tell stories about Sean Doolittle in 2008, how he was the best pure hitter on that team and how he would be taking swings in the batting cage by himself after a game as I was locking the gates–before he turned himself into an All-Star relief pitcher. I can talk about being the first guy to meet Josh Donaldson at the Days Inn in Bakersfield when he was traded to the A’s in 2008. I hold these memories and experiences very dear to my heart and I think they permeate my broadcasts. Had I been with a team where organizations are coming and going, it wouldn’t be the same.”

Bayrouty’s experience is largely anomalous in the world of minor league ball, where affiliates change often as teams search for better facilities or just a change of scenery, but this is not the only way in which Bayrouty has been fortunate. Getting started in any business requires a few lucky breaks to fall one’s way, but more so in broadcasting. A journalism major at Northeastern University in Boston, Bayrouty was interning at Roger Dean Stadium in Florida when he became friendly with Daytona Cubs broadcaster Bo Fulginiti, who later brought him to Stockton as his assistant. When Fulginiti moved on from the Ports, the job became Bayrouty’s.

Mostly, this is how these moves happen; only a handful of jobs become available each year, usually at the lower levels of the organization. But securing a job is only the first step; the tougher challenge is to find opportunities to move up, opportunities which are thin on the ground. “Sometimes I’m almost envious of the players because they can move up based on performance,” says Bayrouty. “Broadcasters can perform at a very high level and yet not catch that break that allows them a chance to move up or a shot at the big leagues.”

The hierarchy that players experience as they move through the minors is prominent for the broadcast team as well, who often work within the same shoestring budgets and unglamorous accommodations as the players. Sometimes a long bus ride is a great opportunity to get to know players as more than their stat lines and scoop up the kind of anecdotal tidbits to enrich the broadcast; but, as Bayrouty says, “there are also those moments when you’ve just finished a seven-game road trip and you have a seven-hour ride home…you wake up on the bus at 2 a.m. and realize there are still three more hours to go before you’re home, and probably another four before you’re in bed. That’s the part of the job that nobody sees.”

Eventually, the long hours, poor pay and distance from friends and family can wear on even the most passionate resolve. David Lauterbach, formerly of the Jackson Generals and now with the MLB and NHL Network, explains: “Working from 10 a.m. to midnight for 20 straight days without a day off isn’t easy at all and is partially why I made the switch. Yes, it’s baseball, but it wears you down and makes the game less enjoyable, in my opinion.”

Lauterbach’s goal is to work in the commissioner’soffice one day, and while he too cut his teeth on the dulcet tones of Vin Scully, he recently found himself being pulled more toward the executive side of things. He’s also finding a traditional office setup with multiple coworkers and a consistent home base to be more agreeable to his personality than the nomadic lifestyle of broadcasting. “It’s an enjoyable gig, but it’s very lonely,” he acknowledges.

Bayrouty cautions anyone who is thinking about getting into broadcasting to understand the grind involved: “There are a lot of people out there that want to work in sports broadcasting because they think it’s fun and easy. It can be fun, but in reality it’s very demanding and in order to do your job well, you have to have a very specific set of skills and be willing to work harder than most people in the work force in terms of hours. Of all the people that want to get into this field, only a fraction will have what it takes to do the job well and only a fraction will come to really understand the sacrifices needed to work at the higher levels.”

And of that fraction who have what it takes—the talent, the drive to get better and the willingness to sacrifice a traditional life to chase this dream—only a fraction of those people will get the precious few jobs that open every year.

When Joe Davis takes over for Vin Scully, he will become youngest play-by-play announcer, and one of just three born in the ’80s (Aaron Goldsmith in Seattle and Jason Benetti in Chicago are the others). Of the 30 major league franchises, each has a broadcast team that generally ranges between eight and 12 people, counting radio, TV and the Spanish broadcast (or French or Korean). These positions are staffed by men and women, ex-players and career broadcasters alike.

But it’s the play-by-play announcer we think of as “the voice of” a team. They’re the ones with the signature calls, the voices that keep us company driving home late at night or nodding off in front of the TV. And they’re voices that overwhelmingly represent one particular experience: the older, white, able-bodied male experience. The White Sox took a step forward when they replaced Hawk Harrelson with Benetti, whose more analytical style may be influenced by growing up in an era that was more sabermetric friendly; he has also written movingly about his experience as a person who lives with cerebral palsy. The more diverse voices that tell baseball’s story, the more people who will be able to see themselves in it. Unfortunately, the wheels turn slowly, and when the public hates to see a legend like Scully go, it likely gives teams even more pause when thinking of making a broadcasting change.

In a sport that struggles to compete with basketball and football for the under-30 market share, it’s time for baseball to move past the notion of the broadcaster as a lifetime appointment. One newspaper article announcing Joe Davis invited fans to meet “your announcer for the next 67 years.” It’s understandable that fans want the comfort of a familiar voice on the airwaves. Life can be hard and change is scary, and it’s reassuring to turn on the radio or TV and feel immediately at home. But ultimately, this kind of thinking serves no one: not the sport, not the fans and certainly not the legions of young broadcasters toiling in obscurity across the country, desperate for a chance to add their voices to baseball’s story.

References & Resources

- Gemma Kaneko, MLB.com Cut 4, “Who is the longest-tenured current broadcaster for every club?”

- Occupational Outlook Handbook, “Announcers Job Outlook”

- Jason Benetti, CNN, “Sports announcer: ‘The way I look is a small part of who I am’”

- Associated Press, SFGATE, “Names and faces: Joe Davis, Russell Westbrook”