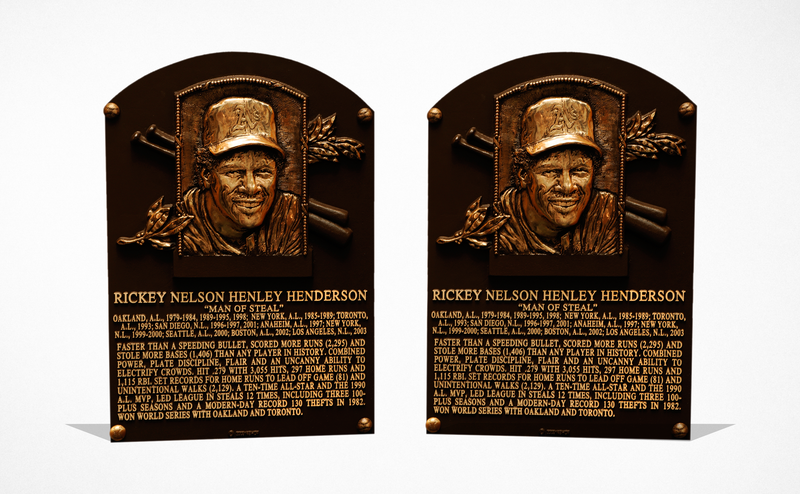

When discussing Rickey Henderson’s Hall-of-Fame prospects, Bill James once wrote that “if you could split him in two, you’d have two Hall of Famers.” It’s a seemingly hyperbolic quip from one of sports’ most precise thinkers. So it’s probably worth a closer look.

Henderson is a pivotal figure in baseball (and all of sports) as an early test case for how advanced analytics can alter our perceptions of a player. His gaudy stolen base numbers and impressive standard batting statistics made him a shoo-in for Cooperstown well before the rise of sabermetrics; his value has grown even further under the analytical lens. More than any single statistic, however, it’s Henderson’s longevity that makes him a legend. It’s not simply that Henderson played for 25 seasons, but that for so many of those seasons he was a productive player, even an elite one.

If you take Henderson’s first 10 seasons, from 1979 to 1988, they total a WAR (wins above replacement, as calculated by Baseball Reference) of 61.5. If you throw all of that out, and use only his stats in the 15 seasons from 1989 through 2003, Henderson had a “second career” with a WAR of 49.3. That’d be good enough on its own for 319th all-time in MLB history, the same as Ralph Kiner and better than the likes of Lou Brock, Dizzy Dean, and many other Cooperstown residents. To put it another way, if Rickey Henderson had never played those first 10 seasons, and only began playing at age 30, he still might be a Hall of Famer. This is what Bill James meant.

So who are the other members of this exclusive club? (In honor of James’s observation we’ll call them the Hendersonian Hall of Famers, though it would be more accurate to call them Ruthian, in honor of the man with the highest second-career WAR, a whopping 80.5.) Who are those players with excellence so long-lived that they had two entirely independent Hall of Fame career arcs? And who’s the current player most likely to join them?

One way to examine this would be to use a method used by Matt Klaassen of Fangraphs. Klaassen suggests dividing a single player’s career into two hypothetical players, determined by a snake draft of that original player’s individual seasons. This method, in which the seasons can be out of order, is designed to account for the fact that the true “halves” (as in, cutting a career down the middle) of players’ careers are often unequal. Using Klassen’s method, a player who lasts 20 seasons could conceivably fit the “two hall of fame careers” criteria while having an unspectacular final 10 seasons, provided the first 10 seasons were near-Bondsian. (Albert Pujols might actually end up with this kind of career. More on him later.)

But we don’t think that method quite captures the essence of James’s comment, because it downplays longevity and emphasizes peak performance. So we’ll use a different method: We’ll divide the careers of players who have played 20-plus seasons in a manner that maximizes the WAR of the “lesser” but still-contiguous half. By doing this, we squeeze out the two most likely Hall-of-Fame windows, each of at least 10 years (the minimum for HOF induction), while keeping the “order” of the individual seasons.

What constitutes a Hall-of-Fame career in baseball is a messy science, even in the age of advanced stats. Special achievements (awards, peak seasons, playoff heroics), the era in which one played (dead ball or juiced ball, for example), and other details (if you played for a big-market team) inform how we judge the excellence of a career. The most popular single measure for overall career value is wins above replacement, which ostensibly translates to the number of wins a player added to his team relative to a replacement-level player at that position. We can use Baseball Reference’s calculation for WAR to get an idea of how good a player was, and use that as a proxy for Hall of Fame chances.

To do this, we determined the list of MLB players who played 20-plus seasons, with two 10-plus-year windows each with a WAR of at least 45. The average Hall of Famer has a career WAR between 60 and 70, although this varies depending on position and era, but 45 is right about where the conversations about a player being worthy of Cooperstown tend to begin.

For example, plenty of well-regarded Hall of Famers have career WARs below 50 or even 40, like Sandy Koufax (49) and Hack Wilson (38.8). (Fitting here, 45 is also very close to the career WAR of Addie Joss (43.7), who played just nine MLB seasons before dying young from tuberculous meningitis, leading the Hall of Fame to waive its usual 10-season minimum for inductees.) So two half-careers with WARs of 45+ suggests the type of long-term excellence that is Hendersonian.

Just 22 players fit this criteria. To put that in perspective, the Hall of Fame contains 220 former Major League players, so the Hendersonians would represent 10 percent of the Hall. (Though not all the Hendersonians are in the Hall of Fame, for…pharmaceutical reasons.) Here they are:

That’s a fine list of the best of the best ever to play the game, along with a couple of real surprises. And when we begin to dig into the data, we learn some really interesting things.

For one, even among the elite, there appears to be a real correlation between the two windows of a player’s career. Sure, the second windows of careers were slightly less productive on average (66.5 first half vs. 61.2 second half), but the Hendersonians did a remarkably good job of maintaining their excellence, as demonstrated by a positive correlation (Pearson’s product moment, r = 0.70) between first career-window performance and second-window performance.

We can also examine the composition of Hendersonians by position. There are seven pitchers, zero catchers, zero first baseman, four second baseman, two shortstops, zero third basemen, three center fielders, and six corner outfielders.

The zeroes at the corner infield positions (first base and third base) are somewhat surprising, especially because first base is usually thought of as a superstar position. Lou Gehrig and Jimmie Foxx came close to Hendersonian, but their careers were cut short in their mid-30s. Perhaps the defensive penalty WAR places on first basemen is too much, though a number of slugging corner outfielders (Ruth, Bonds, Musial, Ott were able to overcome WAR’s defensive penalty for their positions.

We also see a large number of middle infielders and center fielders, who combined defensive contributions at valuable spots with stellar offensive numbers for their positions.

The absence of any catchers from the list is telling; the toll of playing the position places drastically limits those players’ longevity.

So who are the Hendersonian Hall of Famers? For the most part, the list is a good approximation of the truest inner-circle of the Hall, minus a few players who didn’t quite have the longevity (Lou Gehrig, Mickey Mantle, Mike Schmidt) or gave up parts of their primes to military service (Ted Williams).

Perhaps the only raised eyebrows go to Phil Niekro and Gaylord Perry, who snuck onto the back end of the list—they’re the only two Hendersonians with career WARs under 100. But their careers were not only long and successful, but also remarkably balanced between their first and second halves. Most players with WAR totals in the 90s accumulated the majority of their value in the first half of their career, but the knuckleball and spitball really are ageless, and allowed the old-men versions of Niekro and Perry to basically equal the very-good numbers put up by their younger selves.

But the biggest surprise arrives when we ask the question: Who is the next Hendersonian? Who is the active baseball great cramming two Hall of Fame careers into one?

No, it’s not Albert Pujols, who racked up an incredible 81 WAR over his first 10 seasons, but has managed only 20 since then, as he battles father time.

It’s not Clayton Kershaw, who is just finishing up his stellar first 10-year “career,” or Mike Trout, who is barely halfway through his. Both may join the club someday, but it’s too early to safely project now.

The current player most like to be not just a Hall of Fame, but a Hendersonian Hall of Famer is…Adrian Beltre?

Yup.

From 1998 to 2010, Beltre put up roughly 52 WAR. In his six seasons since then, he’s added another 38 WAR. Although he’s in his age-38 season, he was worth more than 6 WAR just last year, and projection systems like ZIPS and Steamer forecasted another 3 to 4 in 2017. (Beltre missed nearly two months to start the season with a calf injury, which is a real risk of age, but he’s been great since returning and should still reach those projections.) If Beltre sticks around another four seasons or so (through age 41), he should be able to creep his second-career WAR total into the mid-to-high 40s.

Beltre would be a fascinating Hendersonian for several reasons. He’d be the first full-time, exclusive third baseman in the club. He’d be only the second Latino on the list (after Alex Rodriguez, and he might even beat A-Rod to Cooperstown), and the first player born and raised outside of the United States. He’s a poster boy for post-globalization baseball, and he’s done it against better competition than so many names already on the list.

We’ve introduced the concept of “Hendersonian” as a measure of both longevity and excellence in sports—it needn’t only be applied to baseball. (We also like it because it further grows the legend of Rickey Henderson, which is never a bad thing.) But the real test of any metric, even a relatively simple one like this, is what happens when you see where the data leads. Does it tell you anything interesting, or surprising? I’d say Beltre qualifies as both.

Cheekay Brandon is an academic computational biologist, a below-average amateur boxer, and quinoa enthusiast. Ben Odell suffers the double misfortune of being an attorney and lifelong Mets fan.