4 Reasons for Nascar’s Big Skid – Bloomberg

I am old enough to remember (that is, I’m older than 15) when Nascar was about to become the new national pastime, the sport of real America that was being eagerly embraced by corporate America because it offered so many places to plaster advertising slogans. I haven’t heard a lot about the auto-racing enterprise lately, though, so while switching channels last Sunday, I paused for a while on NBC’s coverage of the Monster Energy Nascar Cup Series Brantley Gilbert Big Machine

1

Brickyard 400.

Most of what I saw consisted of jostling for the lead by Martin Truex Jr., currently No. 1 in the Nascar Cup Series standings, and Kyle Busch (No. 4), who ended up crashing into each other about two-thirds of the way through the race. But my attention kept wandering to the grandstands at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway. They were strikingly, shockingly empty. Eventually I observed some crowds clustered in the parts of the stands with shade, but according to the Indianapolis Business Journal, only about 35,000 people were there, in a facility with seating for 235,000. Five years ago, the crowd for the same race was four times bigger.

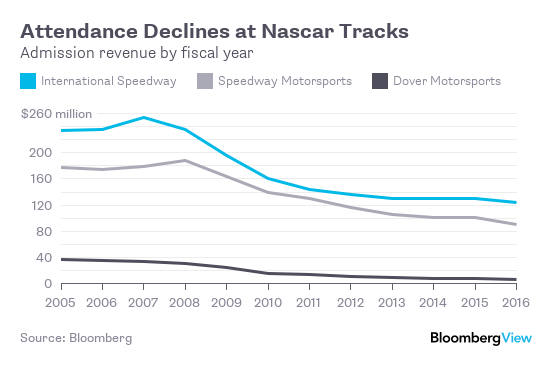

This is not just an Indianapolis problem, it turns out. Nascar stopped reporting race attendance a few years ago, but the publicly traded companies that own most of its tracks

2

do report admission revenue, and it’s way down from a decade ago.

Attendance Declines at Nascar Tracks

Admission revenue by fiscal year

Source: Bloomberg

Nascar television audiences are shrinking, too. Last Sunday’s Brickyard 400 actually got more TV viewers than last year’s, but on the whole viewership was down 12 percent over last year as of early July, and it’s down about half from its peak in 2005.

Lots of spectator sports are suffering these days from flagging interest and competition from other amusements. But Nascar seems to be having a much harder time of it than any other major U.S. sport, precisely when what might be called Nascar-friendly forces have been on the rise in culture and politics. What the heck is happening here? There’s a burgeoning literature on this topic, and while I’ve yet to come across a totally convincing explanation, here are a few theories:

1. It’s maybe not the best-run organization in the world. Although it stands for National Association of Stock Car Auto Racing, Nascar is not so much an association as a family business, with the descendants of founder Bill France Sr. running the show. Grandson Brian France is chairman and chief executive officer. His older sister Lesa France Kennedy is CEO of International Speedway, the biggest track operator. Their uncle Jim France is chairman of International Speedway and, according to an article published in the Wall Street Journal in February, owner of at least half of Nascar. His late brother, Bill France Jr., who led Nascar to national prominence, split his 50 percent stake between Brian and Lesa, but Brian reportedly sold most or all of his share a decade ago (to whom the Journal did not say). A simple if secretive chain of command has thus been replaced by a complicated but if anything more secretive one. “Who’s running Nascar?” legendary former racer and current car owner Richard Petty asked last year. “Where does the buck stop?” Owners such as Petty don’t make nearly enough from Nascar to pay their bills, so they need to sign up car sponsors to get by. That has been getting harder to do as interest in Nascar wanes; the eventual winner of the Brickyard 400, Kasey Kahne, may lose his car soon due to lack of sponsorship. Early last year, Nascar did give the owners a more substantial stake in the system by granting them charters similar to team franchises in other pro sports, which may help. Still, it all seems pretty complicated. Then again, so is Major League Baseball.

2. It’s the economy’s fault. “The economic downturn in 2009 hurt Nascar probably more than any other sport because of the dependence on sponsorship, and because our race fans travel greater distances to our events,” Nascar’s chief marketing officer told Canada’s Globe and Mail early this year. A related argument is that Nascar’s core audience is the white working class and, as we’ve been hearing a lot over the past year, things haven’t been going so great for the white working class. You might say that the same economic forces that helped propel Donald Trump into the White House (Nascar CEO Brian France was an early Trump supporter) have been keeping people from going to Nascar races. But that doesn’t explain why TV ratings have plummeted, too, unless you believe that all the former Nascar watchers are now addicted to cable-news political coverage instead.

3. Nascar got boring. The national media first really began paying attention to Nascar after a 1965 Tom Wolfe article in Esquire titled “The Last American Hero Is Junior Johnson. Yes!”

3

Wolfe affectionately depicted a big-time, lucrative sport that was nonetheless full of quirky regional character, with good-old-boy bootleggers’ sons speeding around rural Southern tracks at 175 miles per hour in souped-up versions of the cars in everybody’s driveways. Nowadays the racers all drive nearly identical “Cars of Tomorrow” for safety reasons, and the most successful drivers of the past two decades have been two blandly pleasant Californians, Jeff Gordon and Jimmie Johnson. A few years ago Charles Murray asked “Do you know who Jimmie Johnson is?” in his widely publicized “Do You Live in A Bubble?” quiz from the book “Coming Apart.” I got that one wrong — I thought he meant the former Dallas Cowboys coach (spelled Jimmy). But I wonder if the issue might have been something other than my bubble: I grew up in suburban San Francisco, far from the Nascar heartland, but I can tell you who Richard Petty and Cale Yarborough and the Allison family and the Dale Earnhardts are or were (I was a faithful watcher of ABC’s “Wide World of Sports,” which frequently featured Nascar). It’s telling that North Carolinian Dale Earnhardt Jr., whose father was one of Nascar’s greats, has been voted the most popular driver by fans for 14 years running despite never finishing higher than third in the sport’s Cup Series. A charismatic, colorful champion or two could probably fix some of this problem, but in general the corporatization and deregionalization of the sport over the past quarter-century seems to have inevitably robbed it of some of its appeal.

4. Fewer people love cars. Putting too much weight on the particular foibles of Nascar may be a mistake given that Formula One auto racing has been contending with a similar decline in interest. This hasn’t really been brought up in any of my Nascar-related readings, but I wonder if it’s just that the great love affair with cars that consumed the U.S. and other affluent countries in the post-World War II decades has given way to a different sort of relationship in which most people simply rely on their (increasingly reliable) vehicles without thinking about them, and only a tiny minority do the sort of tinkering and driving for pleasure that was once common. Autoshop classes have become rare, generally less-fun-to-drive pickups and sport utility vehicles outsell cars by a wide margin in the U.S., and a growing percentage of Americans never even bother to get driver’s licenses. Watching cars drive around in circles for hours is always going to be an acquired taste, but people are going to be far more likely to acquire it if they actually care about cars in the first place.

This weekend, the cars will be driving around not in circles but in triangles at Pennsylvania’s Pocono Raceway, aka the Tricky Triangle, which is as close as the series gets to New York City (the track is actually just barely inside the New York-Newark Combined Statistical Area).

4

Next week it’s on to Watkins Glen, New York, for the I Love New York 355. I don’t think I’m going to make it to either. It will be interesting to see who does.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

-

Brantley Gilbert is a country music star and Big Machine is his label.

-

But not the Indianapolis track, which is owned by the company that makes Clabber Girl baking powder.

-

Johnson said of Wolfe in 2015: “He done more for me than anybody. He done more for NASCAR than anybody.”

-

Note to “Office” fans: Two or three miles farther west, and it would be in the Scranton-Wilkes-Barre-Hazleton Metropolitan Statistical Area.

To contact the editor responsible for this story:

Brooke Sample at bsample1@bloomberg.net