Bob Ley reacts to a Nebraska soccer tournament disqualifying a youth soccer team because 8-year-old Mili Hernandez looked too much like a boy.

GRETNA, Neb. — Lanyard Burgett sits uncomfortably outside a coffee shop in an outlet mall, occasionally craning his neck to see whether someone is behind him. Burgett says he served in the Air Force in Saudi Arabia in the 1990s, but was never as afraid there as he is right now.

His angst is over the events of a youth soccer tournament in Nebraska last weekend.

Burgett says his life has been threatened, and his phone has been bombarded with numerous intimidating calls from blocked numbers. He has filed a report with the Sarpy County Sheriff’s Office. Burgett is not normally a paranoid man, but he was awoken Tuesday night to what he believes was the sound of someone trying to break into his house. He’d been asleep for three hours at that point. It was one of the longest nights he has slept since all this started five days ago.

His body language is a contorted mess of anger, fear and resignation. Burgett has been a ref and a coach and a soccer dad, but right now, the volunteer director of the Ray Heimes Springfield Soccer Invitational never wants to be involved in a soccer tournament again. He is seated across from a public relations person named Gina Pappas, and has come with a stapled packet of soccer rules and a roster — evidence, if you will. Less than a week ago, Burgett’s world was grandkids and making sure he had enough medals for his tournament — a simple life in the small town of Springfield, Nebraska, population 1,600. Now Burgett has a P.R. person.

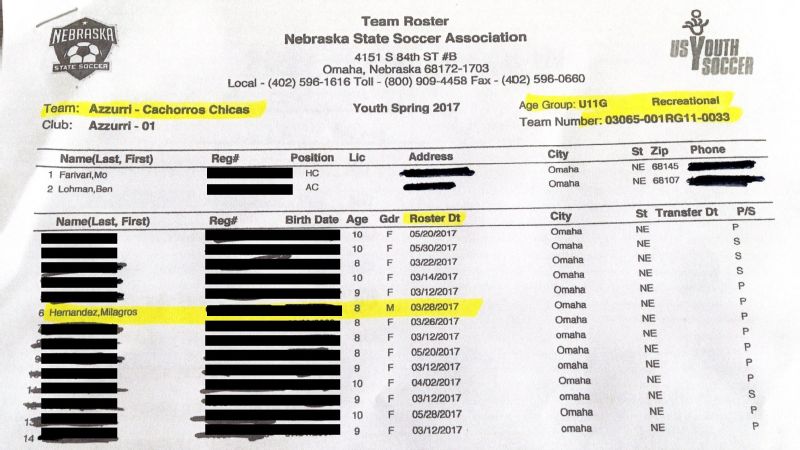

Tournament officials say that Mili Hernandez being incorrectly listed as a male on the girl’s team roster was one of four infractions that led to three Azzurri club teams being disqualified.

About 30 minutes away, in Omaha, an 8-year-old girl is being flooded with media requests. Mili Hernandez had two TV interviews on Tuesday night, and she was late because her father, Gerardo, couldn’t find her. She was out playing with a friend, oblivious to the fact that she has become the face of a debate over sports and gender rights. Mili doesn’t have Barbie dolls; she has soccer balls. On Sunday, when her Azzurri Cachorros Chicas team was disqualified from the tournament in Springfield, reportedly because tournament officials were convinced the short-haired Mili was a boy, the story took off, thrusting her into international prominence.

U.S. Soccer legends Mia Hamm and Abby Wambach sent their support to young Mili, whose full name is Milagros, which in Spanish means “miracles.”

“You’re inspiring,” Wambach told Mili in a video. “You’re a natural-born leader, honey, and I’m so proud of you.”

But like most scenarios involving parents, youth sports and about 1,000 kids running around a grassy patch of land, this story is far from simple.

Burgett tugs on his plastic water bottle. At least twice in the conversation, he looks as if he’s going to cry. He was torn when he heard about Hamm and Wambach reaching out to Mili. He’s happy that the little girl might get to meet them, and upset that he, in this equation, is portrayed as the monster who created the controversy.

He thumbs through his packet of soccer papers, which are marked in yellow highlighter. Two decades in the military taught him to be regimented, even in chaos. It taught him to follow the rules.

“I would like to have the opportunity to maybe sit down with the parents and talk to them and apologize to her,” he says. “Because I want her to know it wasn’t about her. I’ve got grandkids. I wouldn’t want somebody to do it to them when they play soccer.

“I’d like to give them my side. They might understand; they might not. At least then they’d know from my side why I did what I did.”

Many sides to the story

Where do we begin? With the coach who complained about a rule that has nothing to do with gender confusion? With the anonymous parents who asked why a boy was playing on a girls’ team?

Burgett contends that young Mili had nothing to do with the Azzurri girls’ team being kicked out of the Springfield tournament Saturday night. He says he disqualified three Azzurri teams, not just Mili’s. Yes, there was a dispute over whether Mili was a girl that became even more confusing when the team’s roster, a list that has been used for months, had an “M” for male next to her name. There are 14 girls on that roster, and the only one who fell victim to the typo is the kid who just happens to have short hair. How that happened remains unclear.

Azzurri soccer club director Mo Farivari says a typo by the club registrar erroneously listed an M for male next to Mili Hernandez’s name on the team roster.

But Burgett says the teams were disqualified because they violated another rule. Azzurri played kids on multiple teams in the tournament. Burgett presents a piece of paper that Mo Farivari, the director of the Azzurri soccer club, signed at check-in. Six lines above his signature, in caps, is a sentence that says if illegal players are caught, they face possible removal from the tournament. Then Burgett shows a highlighted page that explains the rule, that a kid can’t play on two teams.

Farivari doesn’t deny that the club had players competing on multiple teams during the tournament. Three girls on Mili’s team also played for Azzurri’s 11/12 boys’ team during the tournament. So did a few players on the club’s 10-and-under boys’ team. But Farivari says they’ve done this before, it’s legal at his tournament, and he was never told that it was against Springfield’s rules. Farivari is also convinced Mili’s team was disqualified because of the gender controversy.

“The only reason he disqualified them,” Farivari says, “is because Mili looks like a boy and is listed [with] a typo on the roster. I went over this to clarify, but he didn’t want to listen.”

The gender flap, in and of itself, is confusing. Soccer clubs have a registrar who types in the names of each player, along with information such as date of birth and gender. Months ago, when Azzurri’s registrar was inputting the 300-plus club names into the Nebraska State Soccer Association system, Farivari says, the registrar accidentally hit “male” instead of “female” for Mili. That error apparently was never corrected.

So for months, Mili played soccer games with the wrong gender attached to her name, and heard nary a peep about it. Even a rules-stickler like Burgett didn’t notice during registration as he pored through hundreds of names last week.

Tournament officials first noticed it Saturday. Burgett was gone for a few hours to attend a wedding, leaving duties to his assistants. That morning, Mili’s team was scheduled to play the Norris Titans Blue team after 11 o’clock. Norris had played earlier that morning, and members of the team were watching a boys’ game before warm-ups.

When three girls who played on that Azzurri boys’ team took the field for warm-ups before the Titans’ girls’ game against Mili’s team, Norris coach Brad Kester took notice. It bothered him a bit. “If that was legal,” Kester says, “I would’ve had two teams in the tournament if I could’ve shared players.”

There are reasons for that rule, Kester says. Temperatures climbed into the 90s in Eastern Nebraska this past weekend, and he says safety is an issue when a kid is possibly playing eight games over the course of three days.

Kester alerted a referee about the rules infraction, but he did not protest the game, which he says Norris won 4-0. It was the Chicas’ first loss of the tournament. During the game, Kester says that his players could hear parents yelling for Azzurri to “pass HIM the ball.” That puzzled Kester. He says the shouts were coming from Azzurri parents.

“It didn’t really matter to me,” Kester says. “We didn’t complain about Mili’s role in the game. It had no impact on the game. It’s not like we saw Mili before the game and we’re like, ‘Hey, that player looks like a boy.'”

After the game, when Kester was talking to a tournament official about the player-swapping infraction, he said at least one parent from Norris chimed in and asked, “Why do they have a boy on the team?” Kester declined to identify the parent. Burgett says multiple parents asked that question.

By late Saturday, Burgett and his staff were investigating both issues. Burgett went through the roster and saw the “M” for male. He says he did not actually see what Mili looked like until Monday night, when he finally turned on a television and saw her on the news. (He says he intentionally avoided TV and the internet before that.) Burgett says it didn’t matter what documentation Mili’s family, or the club, presented. His official document, the roster, said she was a boy. And in his mind, the point was moot anyway, because her team, along with two other Azzurri squads, were being disqualified for the player-sharing infraction.

At 11:12 p.m. on Saturday night, he sent Farivari an email informing him that the teams were disqualified. In detail, he listed four infractions. Three of them were about sharing players. But the first one on the list dealt with Mili.

She was not named — Burgett says he made a point throughout the whole process not to single her out — but the paragraph said the Chicas’ first infraction was having a male play three games on a female team.

“I am sorry to inform of this decision,” Burgett wrote about the infractions, “but cheating is not taken lightly and they will forfeit their remaining games.”

Mili back on the field; Burgett not so quick to return

Gerardo Hernandez’s phone has been ringing nonstop. When he got word Sunday morning that his daughter’s team was being disqualified from the tournament, he rushed from his home in midtown Omaha to Springfield, desperately — and unthinkably — trying to prove that Mili was a girl.

Gerardo was angry, but he had to get there so Mili’s team could play. He brought with him an insurance card to prove his daughter’s gender. He was ready to recite any information they needed.

“I said I have something in my wallet I want to show him,” Gerardo says. “He didn’t even take it. He didn’t care. He said somebody was a boy on the team, and there’s nothing we can do.”

Mili went with him to Springfield. Gerardo says she felt like the whole team got kicked out because of her, and she felt terrible. She cried the whole ride home, he says.

“She went to sleep thinking she was going to play … ” Gerardo says. “Early morning, they told her she was out.”

The Nebraska State Soccer Association did not respond to questions from espnW.com, but said in an email that Springfield tournament officials disqualified an all-girls team for incorrectly listing a member as “male” on its roster in violation of tournament rules. The NSSA said that despite initial media reports, team officials said the squad was not disqualified because of physical appearances but because of incorrect paperwork submitted. The NSSA said it was suspending the sanctioning of the Springfield Invitational until a detailed review took place.

In a statement, executive director Casey Mann said Nebraska State Soccer “was founded on the values of teamwork and inclusion.”

Mili hasn’t had to worry about exclusion in the days since her story went viral. Hamm has invited her to her camp this summer, and Mili plans to go. Farivari says he got a call from Columbus, Nebraska, offering the team a chance to play in a tournament there this weekend, free of charge.

Thursday night, according to Azzurri coach Mario Torres, Mili’s teammates plan to cut their hair after practice as a sign of support for her.

Mili is kicking a soccer ball around again and playing with her friends. She seems ready for things to go back to normal. “I want to forget about all this,” she told Omaha ABC affiliate KETV.

Burgett isn’t sure when things will be normal again, but he has no plans to help out with soccer anymore. “I don’t have the passion for it right now,” he says.

For years, when he handed out medals at the tournament, he choked up with emotion. He’s not quite sure why a strict military man would do that, almost cry when a kid received a medal. He just did.

“I’ve had angry parents, angry coaches when I’ve refereed,” he says. “But I’ve never felt that I had to protect myself.

“My wife and daughter are worried right now. They’re just worried because we’ve never been in this situation.”