When American athletes arrive for the Olympic games in Rio de Janeiro two months from now, they will compete in a country embroiled in political turmoil and facing the worst economic crisis since the 1930s.

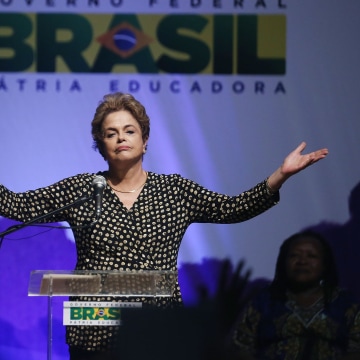

Last month, Brazil’s Senate impeached the country’s first female president, Dilma Rousseff, over accusations that she doctored Brazil’s accounts in order to present a rosier view of the country’s fiscal situation prior to her reelection bid in 2014.

Combine that with street protests, a flailing economy, the spread of the Zika virus and concerns about logistical planning for the Olympics and the result is a country caught in a complicated confluence of events.

“There are so many things coming together here, it’s a matter of serious concern,” says Melvyn Levitsky, the U.S. Ambassador to Brazil from 1994-1998 and a professor at the University of Michigan’s Gerald R. Ford School of Public Policy.

Rousseff is far from the only Brazilian politician embroiled in scandal. Many lawmakers, including leaders of Brazil’s Congress, have been accused of corruption.

Related: Brazil’s Senate Votes to Impeach President Dilma Rousseff

The most notable case involves numerous politicians benefiting from bribes linked to Brazil’s semi-state-owned mega oil company, Petrobras — the board of which Rousseff chaired before becoming president.

Though Rousseff herself has not been implicated in the scandal, the country’s weak economy and corruption within her own Workers Party — combined with her aversion to political hobnobbing — have alienated her from natural allies and is seen by many as the real reason why her removal from office has garnered so much support.

Before Rousseff took office in 2011, Brazil’s economy was booming thanks in part to centrist economic policies implemented by her predecessor and mentor, Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva, resulting in a gross domestic product (GDP) growth of 7.5 percent in 2010. Fast forward five years later, and Brazil’s GDP growth has shrunken massively to -3.8 percent.

Related: Brazil’s President Blasts Impeachment Vote as ‘a Coup’

“The Workers Party government misread the importance of the commodity boom,” said Maria Herminia Tavares de Almeida, a professor of political science at the University of Sao Paulo and a former president of the Brazilian Political Science Association.

Tavares de Almeida adds that during Rousseff’s first term in office, “The control over inflation was loosened … a series of policy experiments on price control and erratic subsidies” multiplied, and “Petrobras suffered from incompetent decisions that also affected the entire energy sector.”

Once commodities stopped propping up Brazil’s economy the country became less fiscally secure.

Frustrations over the economic and political situation in Brazil have manifested themselves as both supporters and opponents of Rousseff have taken to the streets in protest. Levitsky views the problem of street demonstrations as one “that certainly is a threatening one.”

“There has been some violence in the streets and some brick throwing,” Levitsky says. “You could have some real disruption in the streets just because of the chaotic political situation.”

Officials can’t predict what more will happen in the coming months and whether or not there could be a possible disruption of the Games.

Rousseff is to stand trial for a period of no longer than 180 days and the verdict will determine whether she is ultimately removed from office. In the meantime, Vice President Michel Temer is taking over the presidency on a temporary basis — though his brief time in that role has not exactly been smooth sailing.

Temer, who is also under investigation for alleged corruption, was criticized for having a cabinet full of ministers devoid of much ethnic or gender diversity.

According to Tavares de Almeida, while Temer’s troubles may help Rousseff “maintain the loyalty of party activists,” that alone may not be enough to bring those she has alienated in Congress back to her side in order to avoid being removed from office.

Issues directly relating to the Olympics, however, are also plaguing Brazil during this fragile time.

For example, concerns have been raised about facilities, including the flagship velodrome, being completed on time. Rio de Janeiro’s government recently terminated its contract with the venue’s building company, Tecnosolo, after it filed for bankruptcy.

Though bacterial and virus pollution in Rio’s waters has improved, the Zika virus is still pervasive enough that a spokeswoman for the U.S. Rowing Association told NBC News that its medical committee is developing a Zika virus plan.

Another challenge has been convincing people to actually attend the Rio games. As of late May, only 67 percent of tickets to the Olympic games have been sold and just 33 percent of tickets to the Paralympic games — amplifying just how much the narrative of a struggling preparation effort has reached the public. By comparison, tickets to the 2012 London Olympics had sold out for every sporting event except soccer by February of that year.

Despite these concerns, however, many U.S. Olympic teams are thus far opting to take everything in stride.

Olympic coaches interviewed by NBC News expressed confidence that the Olympics could effectively be shielded from the country’s political turmoil. (NBC Sports, which along with NBC News is a programming division within NBC, has broadcasting rights to the Olympics in the United States.)

“The reality is that probably being in Rio in 2016” for the summer Olympics “is going to be one of the safest places to be at knowing the levels of security,” said Greg Massialas, the fencing coach for the U.S. men’s foil team and a former Olympian himself. While Massialas admits that there’s a certain level of uncertainty, he contends that “there’s always a coming togetherness that is special about the Olympics.”

Massialas competed at the 1984 Olympics in Los Angeles and said he remembers all the fear before the games over unbearable traffic jams.

“There was no traffic at all during the games,” Massialas said. “It brought all the people together to make sure that things happened well.”

And he doesn’t think political concerns will impact his athletes.

“We have an experienced squad of people,” Massialas said. “They understand they have a mission and a goal in front of them and they’re not going to let these things distract them.”

Dejan Udovicic, the U.S. men’s water polo coach, largely agreed.

“Every Olympic games got some issues,” said Udovicic, the former head coach of Serbia’s national team, adding that eventually “everything is fixed.”

Brazilian officials also brushed off concerns that the political climate could upend the games.

“Brazil has faced other crises and Brazilians have always worked together to overcome difficulties. It will not be different this time,” a spokesperson for Brazil’s Sports Ministry under Rousseff told NBC News. “The Rio 2016 Olympic and Paralympic Games will take place in an atmosphere of peace, harmony and will be successful.”

Prior to her impeachment, a spokesperson for President Rousseff’s administration told NBC News that Brazil “is not worried about any negative impact of the current political situation on the Olympic Games” though “the political crisis is making it more difficult for people to see that the organisation of the Games is doing well and the venues are ready.”

While it’s not entirely clear how much this series of tumultuous events will directly impact the Olympic games, it’s certain that the public’s confidence in a successful Olympics occurring is being put to the test.

“I tend to think that they’ll get through it,” says Levitsky. “But it’s not going to be pretty.”