Stevenage, the first of England’s post-war New Towns, was widely proclaimed in the 1960s as a shining example of how the provision of high-quality, joined-up cycle infrastructure would encourage many people to cycle – not just keen cyclists.

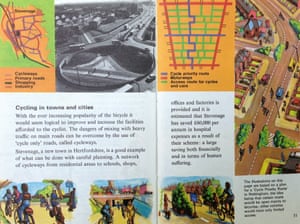

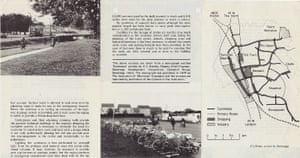

The town, 30 miles north of London, had wide, smooth cycleways next to its main roads which were separated from cars and pedestrians. There were well-lit, airy underpasses beneath roundabouts, and schools, workplaces and shops were all linked by protected cycleways.

Stevenage still has these cycleways. Throughout the 60s and into the 70s, it was put forward as proof that the UK could build a Dutch-style cycle network. An article in New Scientist magazine in 1973 claimed that “Stevenage cycleways and cycle underpasses [are] premiere exhibits … [in a] traffic revolution.”

This revolution flopped. Few outsiders have any inkling that Stevenage is veined with the kind of separated cycleways commonplace in the Netherlands, and even locals are largely unaware they have a 23-mile cycle network.

The borough council did not apply to become a “cycling demonstration town” when Cycling England offered fat grants for local authorities to encourage cycle use in 2005.

The organisation was seeking “low hanging fruit”, and if its expert board members had been aware of Stevenage’s cycleways at the time they might have chosen to target the town in a bid to boost bike use, says former Cycling England head Phillip Darnton.

“Stevenage would have been interesting because it clearly already had some good cycling infrastructure,” he adds, “but a burning question would have been, why wasn’t it being used?”

A failed revolution

Eric Claxton, the lead designer of post-war Stevenage, had believed that use of cycleways would be high if they were well built – originally thinking that Britain’s hostile road environment discouraged people from cycling.

Construction of the cycleway network was given the go-ahead in 1950, built at the same time as the primary road network.

Stevenage was compact, and Claxton assumed the provision of 12 ft-wide cycleways and 7 ft-wide pavements would encourage residents to walk and cycle. He had witnessed the high usage of Dutch cycleways, and he believed the same could be achieved in the UK.

But to Claxton’s puzzlement and eventual horror, residents of Stevenage chose to drive – even for journeys of two miles or less. Stevenage’s 1949 masterplan projected that 40% of the town’s residents would cycle each day, and just 16% would drive. The opposite happened. By 1964, cycle use was down to 13%; by 1972, it had dropped to 7%. (Today it has less than half that, and yet some neighbouring towns with few cycleways have cycling modal shares of 4-5%.)

Claxton poured scorn on those who chose motorcars rather than bicycles, complaining that motorists “seem to have a problem with their logic” because “they use their cars as shopping baskets, or use them as overcoats”. Claxton complained that he had provided “cycle tracks [modelled on the] pattern of those found [in] Holland” for the residents of Stevenage, but cycle use in Stevenage never reached Dutch levels of use.

Too easy to drive

Today’s network may be faded and – because of a few network truncations – somewhat less useful than the one Claxton put in place, but there are still wide, separated cycleways next to the primary roads; glass and debris is regularly swept away by council clean-up squads; some of the cycleways have been recently resurfaced; and in many places, cyclists and pedestrians are still kept apart by barriers, not just paint. Squint, and – where the infrastructure is intact, under the free-flowing roundabouts, for instance – you could be in the Netherlands. Except there are very few people on bikes.

Stevenage’s 2010 master plan complained that just 2.9% of the Stevenage population cycled to work, which was “much lower than might be expected given the level of infrastructure provision”.

The borough council’s cycle strategy – not updated since 2002 – conveys no doubt as to why cycle usage is so low: “Stevenage has a fast, high-capacity road system, which makes it easy to make journeys by car. Residents have largely been insulated from the effects of traffic growth and congestion and generally there is little incentive for people to use modes other than the private car … [The] propensity to cycle [appears to] depend on factors other than the existence of purpose-built facilities.”

Claxton was a regular user of the cycleways he had created. “I didn’t do my cycleways for cyclists,” he told an environmental magazine in 1977. “I did them for people.”

There are safe cycle routes from homes to schools, but today only a tiny proportion of Stevenage’s children cycle each day. Many are ferried to school by car, a situation that Claxton abhorred: “It is pathetic to see the way some parents bring their child to school by car and later park in the street near to the school to give them a ride home.”

Stevenage’s 2010 master plan says the town’s “compactness … forms the basis for sustainable movement patterns,” but even though a “large proportion of the town is within a 2km cycle ride … of the town centre, [the] preferred mode of transport to the town centre is the car.” Stevenage’s residents are in thrall to the car, even though perfectly safe and convenient alternatives to motoring are provided.

Despite all the best efforts of a chief designer with empathy for would-be cyclists, “build it and they will come” failed for people on bikes in Stevenage but worked for people in cars.

In 1992, Claxton had warned: “What a dreadful example these car drivers are setting for future generations … They become selfish and almost exclusively travel alone. They do not care about others.”

But by not restraining motor vehicle use – and instead encouraging it with concrete – town planner Claxton is partly to blame for the bad behaviour he described.

Plenty of politicians – and newspapers – describe restraining car use as a “war on the motorist” but to encourage healthier forms of transport such measures will be needed and they need to be included in parallel with the provision of safe cycling infrastructure, Darnton believes. “If the reasons for Stevenage’s failure to encourage cycling were that it was too easy to drive, then no amount of investment in marketing the town’s cycling facilities would have changed travel behaviour.”

Follow Guardian Cities on Twitter and Facebook to join the discussion, and explore our archive here