At No. 5 Experimental Primary School in the coal-mining city of Taiyuan, the red carpet is out. School girls in pink and white stand at the entrance, while fellow students sit in perfect rows inside, awaiting the arrival of a VIP.

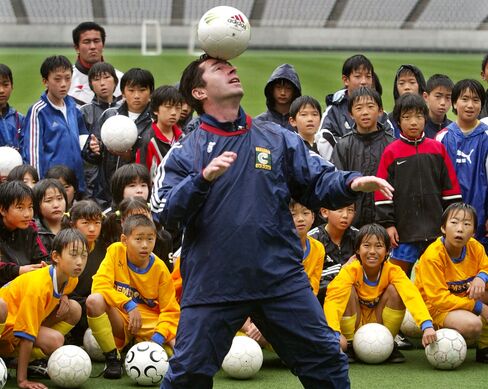

With the city’s education chief and other local dignitaries on the stage and TV cameras hovering in the background you might expect a foreign leader or Communist Party bigwig, but the guest of honor is Tom Byer, 55, a soccer coach from New York.

Byer was starting a tour of schools in 32 cities as part of an ambitious plan by President Xi Jinping to extend China’s soft power using the world’s most popular sport. The goal is to train 30 million kids in the next four years and build a national team by 2050 that can beat the likes of Brazil, Argentina and Germany.

“Xi has promised to make China great,” said Andrew Nathan, professor of political science at Columbia University in New York. “Winning at sports is not necessarily quick and easy, yet with a population China’s size and a government with these kinds of resources, it is a goal that is achievable more quickly than some of the bigger goals. Winning is winning is winning – it’s not complicated, and it goes over great on TV.”

The government aims to have more than 70,000 soccer pitches by 2020 and is hiring coaches from abroad to help teach the game.

Byer is already famous in Japan for having helped transform soccer there. He had a show on national television for almost 15 years, as well as a best-selling manga comic book for his lessons. In that time, Japan rose from soccer nonentity to record four-time Asian champion.

“It’s doable,” he says, after an exhibition class with the pupils in Taiyuan under a banner that reads: The New Long March of Campus Soccer. “The top-down approach works in China: It gets people moving, it gets them into action.”

Hong Kong Loss

It will be a long march. China is ranked 78th in the world by FIFA, the sport’s international governing body, behind St. Kitts and Nevis (population: 50,726) and three places above Equatorial Guinea (1.2 million). Last autumn its much-maligned national team twice failed to beat Hong Kong, ranked 142nd.

In recent matches, China lost 0-1 at home in a friendly against Kazakhstan, ranked 83rd in the world, and in World Cup qualifiers was beaten 3-2 by South Korea in Seoul, drew with Iran and lost at home to war-torn Syria.

Yet Byer is upbeat. The author of “Soccer Starts at Home” points out that Japanese soccer was nowhere in the 1980s and the nation has qualified for the past five FIFA World Cups.

“China’s the only government in the world that has a policy behind football,” said Byer, who is filming a soccer skills show for China Education Television. “Are the goals achievable? I think they are. It’s not like they are completely useless, losing games 8-0 or 6-0.”

Xi unveiled a 50-point plan last year to overhaul soccer in China with backing from state-owned and private companies. It triggered an avalanche of spending by clubs on foreign stars, from $56 million spent on Brazilian Alex Teixeira by Jiangsu Suning to the record-breaking $61 million paid by Shanghai SIPG for Givanildo Vieira de Souza, the Brazilian striker known as Hulk.

Led by some of the country’s richest men, including Dalian Wanda Group Co. founder Wang Jianlin and Alibaba Group Holding Ltd’s Jack Ma, Chinese businesses have spent at least $1.7 billion on sports assets since the start of 2015, mostly in soccer, according to data compiled by Bloomberg. Five years ago, the investment was virtually zero.

Big Clubs

A large chunk of the money went on European clubs. Nanjing-based Suning Holding Group Co. in June paid 270 million euros for 70 percent of 18-time Italian champion Inter Milan. Last year, China Media Capital spent $400 million for 13 percent of English club Manchester City, which currently tops the English league.

Some of the deals have been criticized for overpaying or lack of expertise.

Tech Pro Technology Development Ltd., a property manager in Shanghai and manufacturer of LED lights, invoked the ire of fans after buying France’s Sochaux-Montbeliard last year for 7 million euros ($7.8 million) from automaker Peugeot SA, which founded the club 87 years ago. The team’s future is now in jeopardy after the Chinese company’s shares fell about 90 percent in Hong Kong this year.

“Implementation has gone badly wrong” for Xi’s plan, said Briton Rowan Simons, who runs China ClubFootball FC in Beijing, which trains and organizes leagues for more than 3,000 children. “We have seen already billions of dollars wasted.”

Tiger Moms

One of Xi’s biggest challenges is parents. China is a nation of tiger moms, not soccer moms.

Zhao Tingting in Jining city on the east coast says her 8-year-old boy doesn’t have time to play the game. His extra-curricular activities include calligraphy, piano, English and playing with Lego (to help his architectural skills).

“I want him to focus on his studies,” said Zhao, 34. “There’s little space left for sports.”

Still, the president’s endorsement carries a lot of weight in China — news about his activities sparking trends and spending. He posed for a selfie last year at Manchester City with former U.K. Prime Minister David Cameron and the club’s Argentine star Sergio Aguero.

“China’s soccer plan is a strong signal for the whole people,” said Wang Gaonan, founder of Beijing software company Capstone Games, designer of the top-ranked mobile soccer game in Apple Inc.’s China store. “Every Chinese gaming company has started designing soccer games.”

China has shown before that it can produce winners. It began a program to gain glory after the 1984 Olympic Games in Los Angeles, when it took home 15 gold medals. By the time the nation hosted the event in 2008, it won 51 golds.

“They got results,” said Gilberto Silva, part of the Brazilian team who beat China 4-0 on the way to winning the 2002 World Cup. “They can do it in football.”