“I was a bit naive,” admits Jeffrey Lim. “I thought it would be easy.” In Lim’s bright studio in Kuala Lumpur, bike wheels adorn the walls and a large table is spread with maps of Malaysia. Lim, a graphic designer, has spent the past three years mapping the city for cyclists.

To anybody familiar with Kuala Lumpur’s urban sprawl, “naive” might seem like an understatement. As residents will tell you, this is a city built for cars. According to Nielsen, Malaysia has the third highest rate of car ownership in the world – a whopping 93% of households own a car.

“We were a nation which built bicycles. But we forgot,” says Lim. In the 1960s and 70s, rapid urbanisation in Greater Kuala Lumpur saw new highways straddle the city and the suburbs. In the 80s, the invention of a “national” car sealed Kuala Lumpur’s fate as a motorised metropolis.

Yet in recent years, a group of determined cyclists have taken to the roads nonetheless. At night or early in the morning, drivers and motorcylists might be startled to see a convoy of cyclists suddenly appear. Lim – a youthful looking man with spectacles and a focused demeanour – is often among them, helping to shepherd the group.

Lim first got the idea for a bicycle map in early 2012. He wanted to show how the city could work for cycling – “not for leisure, but for transportation, for utility.” Knowing that most people thought of cycling as “impossible” in the city, he envisioned the map as a tool for advocates. “It was aspirational,” he says. “Because the map would have to come before the infrastructure.”

After getting the word out, Lim designed a blank map of the city to hand out to volunteers. With no dedicated cycle lanes in the city, the idea was for people to explore the routes that were at least possible to cycle, from major roads to unmarked paths. Routes would be marked according to their accessibility for cyclists.

Over a few months, Lim’s studio – which he used to restore vintage bikes – became a weekly gathering point for volunteers. “Every week, new people came. I stopped counting when it went over 50,” he says. “At that point, I had to start a Facebook group specifically for this project.”

Some volunteers reported back with phone calls, some drew sketches, others sent him photos. “Slowly, the map took over my life,” says Lim. He spent months curating the information. Noticing that most of the cyclists were English speakers living in certain urban clusters, he recruited bilingual volunteers to connect with communities in other parts of the city.

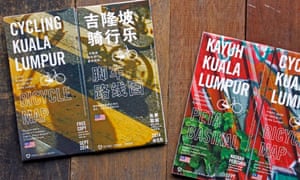

After two years and three drafts, the map was completed in September 2014. It was published in three languages – English, Chinese and Malay – and distributed for free, with a print run of 10,000.

From the beginning, the map had been a grassroots project, crowd-sourced with data from the cycling community. But as word of mouth grew, several local councils contacted Lim to find out more. Now he had a new challenge in front of him: to turn the map into real infrastructure.

“It was interesting to see they took it seriously,” says Lim. While the government had talked up cycling in the past, this had largely been lip service. “It was not at the top of their list. Even though it was stated that, yes, cycling and walking were very important, it was not stated what, where and how.”

The bureaucracy of different government layers was another big obstacle. “Federal government, state governments, departments and city councils – they were all pointing fingers at each other,” says Lim.

To go beyond paper-pushing, Kuala Lumpur needed a pinch of luck. That luck was its mayor: Tan Sri Ahmad Phesal Talib, who took office in 2012. The mayor happened to be an avid cyclist and he called Lim in for consultation.

On a breezy morning in April this year, Lim and his volunteers cycled alongside the mayor as he inaugurated Kuala Lumpur’s first official bicycle lane. After more than a year of planning, it was finally open: a 5km cycling corridor connecting the satellite city of Petaling Jaya to the historic centre of Kuala Lumpur.

Kuala Lumpur City Council went on to approve funds for two more cycling lanes in other parts of the city, with a total budget of £765,000. Lim has continued to consult with other city councils around Malaysia.

“I’m happy the map project is over. I’m happy that we have a document and I’m glad that other people find it useful,” says Lim. “I wanted to change people’s perception about cycling. That was the most important thing.”

Of course, it will be a long time before Kuala Lumpur is a bike-friendly city. To date, there has been no directive from the federal government for a cycling master plan. Lim fears that this will hold back long-term infrastructure, especially since city councils rotate their posts every three years.

But, slowly, a cycling culture is growing here. As well as the new cycle routes, residents now enjoy two car-free mornings in the city every month. There’s also talk of a bicycle festival at the end of the year.

“The map connected all these like-minded people and created a strong community,” says Lim. “It started the ball rolling. No matter how small the move, it’s still a stepping stone for the next move – by whoever.”

Ling Low is editor of Poskod.MY. Follow Guardian Cities on Twitter and Facebook and join the discussion