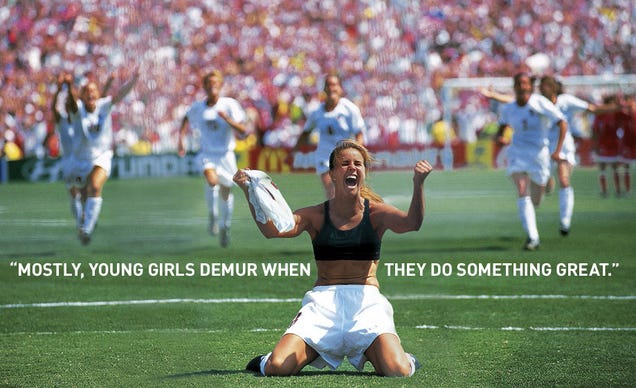

It was arguably the biggest moment in the history of American women’s sports, and the single most memorable and reproduced image of the celebration. Brandi Chastain had just converted the penalty kick that cemented the 1999 Women’s World Cup for the United States over China. She then experienced a fit of irrational and spontaneous exuberance: perched on her knees on the turf of the Rose Bowl, the white jersey that she’d whipped off her torso clenched in one hand, screaming to the heavens as over 90,000 fans (including President Bill Clinton and, um, me) roared their approval and her teammates and coaches raced to embrace her.

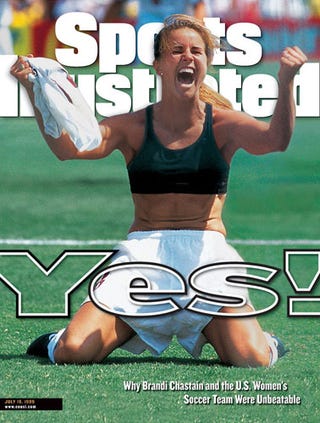

Images of Chastain’s bare midriff and black sports bra were featured on the covers of Time and Newsweek, as well as on countless newspapers. But the most indelible and reproduced picture is the full-frontal photo that appeared on the cover of the July 19, 1999, edition of Sports Illustrated, taken by staff photographer Robert Beck.

Last year, the cover was voted the magazine’s second most iconic cover in its 60-plus year history behind only the wordless “Miracle on Ice” cover from 1980. As Team USA prepares to kick off in Canada, the photograph remains the defining image of the wildly successful run enjoyed by the women’s national team: four Olympic gold medals (1996, 2004, 2008, 2012), ten Algarve Cups (2000, 2003-5, 2007-8, 2010-11, 2013, 2015) and two World Cups (1991, 1999) in the past quarter century.

And yet, interviews with Chastain, Beck, and former national team coach Tony DiCicco suggest that history—and documenting it—is neither so simple nor so linear. Chastain was a last-second choice to take the penalty kick, and at the moment he snapped the iconic photo, Beck had just snuck his way to a spot in which he wasn’t supposed to or prepared to be.

“It was probably something that never should’ve happened,” Beck said, “because I was in the wrong place at the right time.”

Chastain put it more cosmically: “It was fate that brought us together.”

“Brandi, can you kick them left-footed?”

Chastain, a northern California product, was a forward on the U.S. squad that won the inaugural Women’s World Cup in 1991. But injuries slowed her, and she had to change positions, first to midfielder and then to defender. When she was cut from the 1995 World Cup team, it appeared that her career might be over. “It could have ended there,” she said. “But I decided that wasn’t going to be the end of the story.”

She rejoined the national team in time for their gold medal-winning match against China at the 1996 Olympics. Her play was suffused with what DiCicco identified as pure passion for the sport itself. “More than anyone else on that team, Brandi was the most sophisticated soccer fan,” he said. “When we were in residency in Florida, Brandi would say, ‘Tony, can we get a couple of vans and go over to watch the [MLS’s] Tampa Bay Mutiny?’ We would get the vans, but it was her idea. She just wanted to watch top-level soccer.”

In the run-up to the 1999 World Cup, Chastain was a member of the U.S. team that traveled to Portugal for the prestigious Algarve Cup. Early in the second half of the final—again against China–Mia Hamm was dragged down in the penalty area. DiCicco chose Chastain to take the penalty kick.

As Chastain placed the ball on the spot, she found herself confronted by goalkeeper Gao Hong. “She stood right in front of the ball and kind of confronted me, like two boxers in a ring,” Chastain said.

Her shot caromed off the top of the crossbar. China triumphed, 2-1.

“That really unnerved me,” Chastain said of her staredown with Gao. “She had the psychological edge in that moment.”

As technically sound as Chastain was, DiCicco felt that she had gotten too predictable with her PK, always using her dominant foot and going the same way. “She always kicked it right-footed and to the goalkeeper’s right,” he said. “I said to her, ‘Brandi, can you kick them left-footed?’ She said, ‘Yes.’ I said to her, “You gotta practice left-footed because, right now, you have to show the goalkeepers something different.’”

Chastain and her teammates were the favorites to capture the 1999 World Cup, given their experience, their victory at the Atlanta Olympics, and their home-turf advantage. But China was confident, bolstered by their wins over the Americans in Portugal and, in April, in a friendly at the Meadowlands that ended the U.S.’s 50-match home winning streak. Defending champion Norway and Germany, which would win the next two World Cups, quietly lurked.

If you had asked Robert Beck for his pick, he would have blankly admitted that he knew next to nothing about soccer. His sport was surfing, and first made his mark shooting the action in Southern California and Hawaii for Surfer Magazine. In the mid-1990s, after he was hired as a staff photographer at Sports Illustrated, his repertoire expanded to include football, basketball, MLB, the Olympics, and whatever else the magazine wanted him to shoot.

The gig was one of the most prestigious in photojournalism. Since its first issue in 1954, Henry Luce’s brainchild had put the illustrated into sports. This was particularly important in the magazine’s formative years, before televised sports became so entrenched in our living rooms. SI’s vaunted lensmen—Hy Peskin, Robert Riger, John Zimmerman, Neil Leifer, Walter Iooss Jr., Heinz Kluetmeier—were as treasured as the magazine’s staff writers, and Time Inc. cashed in on both by selling innumerable coffee-table books suffused with colorful action images and top-notch sports lit.

“We’ve had the best photographers in the business run though our company,” Beck said. “Even now, if you wanted to put five of our guys against five guys from Getty at some event, we’d come back with better images.”

By the summer of 1999, even the soccer-challenged Beck couldn’t help but notice how the women’s national team had captured the attention of the country. The media fawned over the players, emphasizing the fact that several of them had children. (Real-life soccer moms!) They were seen as spunky exemplars of “grrrl power,” but the wholesome, bouncy-ponytail variety.

And they were winners, unlike the men’s team. They set the tone in their opening World Cup match, a 3-0 drubbing of Denmark before a sold-out crowd of 78,972 at Giants Stadium, with Mia Hamm drilling home the opening goal set up by Chastain’s long ball. They dispatched Nigeria, 7-1, at Soldier Field in Chicago, and then North Korea, 3-0, at Foxboro Stadium to win their group.

The competition tightened in the knockout stages. Chastain made headlines for the wrong reason in the fifth minute of the quarterfinals against Germany, when her errant pass back to goaltender Briana Scurry caused an own goal. Not a natural defender, Chastain never let the error get to her. “Brandi was such a student of the game,” DiCicco told Sports Illustrated in 2014, “that she understood that if you’re a defender, own goals come with the territory. Still, that was a tough one.”

She made amends early in the second half, volleying the ball into the net to tie the game, and the U.S. rallied for the 3-2 victory. On July 4th, they downed Brazil, 2-0, to reach the finals. Meanwhile, China sailed through their draw, whipping Sweden, Ghana, and Australia and then handling Russia and Norway in the knockout rounds. Led by Sun Wen, their offense was clicking, with 19 goals for and only two against.

It was the finals matchup that both teams–and the public–wanted: the United States versus China; the Olympic gold medalists versus the Algarve Cup champs; white Nike uniforms against red Adidas kits; the two clear best teams in the world.

Before the match, DiCicco and his staff debated which players to use if it went to penalty kicks. “The only real controversy we had was about Brandi Chastain,” he said. “[Assistant coach] Lauren Gregg felt that [Brandi] didn’t have a really good year taking penalty kicks and questioned whether we should have her in the lineup. I felt Brandi should take the penalty. A lot of players don’t want to be there. They don’t want that responsibility. I felt Brandi would be okay with that responsibility.”

They agreed to disagree, and the issue was left unresolved.

“We have to get onto the field.”

Sports Illustrated assigned Beck and two other staffers to shoot the finals at the Rose Bowl. The more experienced hands, Peter Read Miller and George Tiedemann, had field passes. Beck was relegated to an upper section of the stadium. His main gig was not to shoot the game, but to photograph President Clinton and the fans, as the crowd was expected to be the largest ever to attend a women’s sporting event.

Pasadena in summertime, outdoors and in the afternoon, is two stops before hell. July 10, 1999, was no exception. Beck sweated through most of the first half awaiting the late arrival of President Clinton. He finally made it back to his spot, by the tunnel in the southwest corner of the stadium, just before halftime.

Beck hadn’t missed many scoring chances in a taut, scoreless first half. As the heat slowed the pace to a sodden crawl, DiCicco used his three substitutes to get fresh legs into the contest. Veteran Michelle Akers, the team’s best penalty taker, was replaced after 90 minutes.

Beck had brought along Todd Curran, an aspiring coach, to help him carry his equipment and to advise him on the soccer action. He asked Curran what would happen if the game ended in a draw. Curran explained that the teams would play two overtime sessions; if the score was still tied, penalty kicks would decide the outcome. Despite his lack of soccer knowledge, Beck immediately recognized the drama of the moment. He told Curran, “This [position] won’t work for something that’s going to happen down there. We have to get onto the field.”

“I wanted to watch the overtime,” Curran said, “but he was thinking ahead. He knew that in order to get a picture that’s going to mean something, we needed to be on the field. I remember him saying, ‘Hey, we’ve got to motivate now. We can’t wait for this to happen.’”

Beck asked Curran which goal would be used for the shootout. “I had to guess,” Curran said, “but I figured that they were not going to put the sun in the goalie’s eyes.”

They gathered Beck’s equipment and made for the goal on the opposite side of the stadium. Wearing red bibs that identified them as credentialed photographers, they “motivated” to the tunnel that led to the field. They marched and bluffed and, according to Curran, “weaseled” their way through the media security checkpoints. “We just acted like we knew what we were doing and where we were going,” he said.

“As soon as the game ended, we walked onto the field,” Beck said. “Nobody paid attention to us.”

Beck saw that his SI colleagues, Miller and Tiedemann, were stationed on either end of the touchline. The only vacant area was in the middle. He and Curran stepped over a little fence and found themselves directly behind the goal.

It was perfect–until they were spotted. “All of a sudden I hear someone yelling at us from behind,” Beck said. “I turn around and it’s security. The guy tells me, ‘You aren’t allowed to be back there.’ I said okay and we started getting our stuff together. Then they grabbed this other [photographer]–I think he was with the L.A. Times–and physically took him over the fence. By the time we turned to go, the security guy says, ‘Just stay there, don’t move,’ because they were about to start the shootout. They didn’t want movement behind the net.”

They were stuck exactly where Beck wanted to be.

At the end of overtime, both teams had to give the referee a lineup card with the names and the order of the first five penalty kickers. DiCicco asked Lauren Gregg to put together a list based on the players left in the game. Gregg put Julie Foudy fifth, with Chastain sixth.

“I said, ‘I like the list, but flip-flop Julie and Brandi,’” DiCicco said. Then he had another thought, and told Gregg, “Ask Brandi if she wants to take it.”

Chastain was on the sideline getting water and stretching her legs. Gregg came over and asked her if she wanted to take a penalty kick. “I thought, that’s kind of a strange question,” Chastain said. “But my immediate reaction and response was ‘yes.’”

Moments later, DiCicco approached Chastain. “You’re going to take a kick, but you have to take it with your left foot,” he said.

Chastain agreed. “It didn’t even dawn on me that I’d never done that before in a game,” she said. “I practiced every kind of kick, every kind of pass, every kind of cross, with both feet. I was comfortable, but I had never taken a left-footed penalty kick in a game before.”

She and her teammates gathered at midfield as China took the first attempt of the shootout. Xie Huilin scored on Scurry. Carla Overbeck matched for the U.S., beating Gao Hong. Qiu Haiyan tallied, only to be answered by Joy Fawcett.

The third Chinese kicker was Liu Ying. As she approached the ball, Scurry anticipated the shot. The keeper jumped out and dove to her left to make the clutch save. The crowd crescendo-ed and then reached another level after Kristine Lilly scored to give the U.S. a 3-2 edge.

Beck was using film, as all photographers did in those days. Each roll of film had only 36 shots, so Beck only took a couple of pictures of each penalty kicker. “I knew I didn’t have a lot of time to shoot a whole bunch, change film, shoot a whole bunch more,” he said. “It’s not how you would shoot it today.”

“That little spot was pretty amazing,” Curran said of their perch behind the net. “But I couldn’t be in awe of the moment because I knew that, as soon as the PKs were finished, he was going to burst out on the field and take as many candid shots as he could and I was going to have to be right on his tail.”

Two players on each team remained. Zhang Oujing scored on Scurry, and then Mia Hamm regained the edge for the Americans. Sun Wen, China’s star, kept the pressure on by calmly netting the equalizer. United States 4, China 4. One American left to shoot.

Chastain, wearing number 6, walked briskly from midfield, a solitary figure in white striding across the green expanse of turf.

“The only thing I could hear in my head was, ‘don’t look at the goalkeeper,’” she said, remembering how in Portugal Gao had intimidated her into hitting the crossbar. “Because I didn’t want to allow her to have that moment again.”

She caught the ball from the referee and placed it on the 12-yard spot. She took several steps back toward midfield before turning to face the net. She tapped the toes of her left boot into the turf.

Some 90,000 sweaty spectators quieted. A domestic television audience of nearly 18 million viewers heard announcer JP Dellacamera deliver the setup: “The U.S.A. could win the World Cup on this next kick. Chastain will take it.”

At the whistle from the referee, Chastain didn’t hesitate. With her left foot, she buried a line drive into the netting, beyond Gao’s futile dive to her left.

“My intention was to hit it to that side and to hit it with my laces,” she said, “just as I had been doing in practice. When I watch it again on replay, it sometimes makes me nervous. I’m thinking, ‘Boy, that is not going in.’ That was way too close.”

Chastain turned to face her teammates at midfield and, in one motion, tore off her uniform top to reveal the best set of abs since Linda Hamilton staved off the Terminator. She sank to her knees and let out an exultant cry that no one but she could hear.

The Rose Bowl was shaking, but Beck stayed focused on his subject. Using a mid-range zoom lens (70-200mm), he framed the shot as a horizontal so as to capture Chastain’s teammates rushing up behind her.

“When she made the winning kick and took her top off, it turned into something completely different,” he said. “I had a version that nobody else had because I was directly behind the net.”

Beck wondered if he had gotten the shot. “We used to ship our film immediately back to New York,” he said. “Peter Read Miller was driving me to the airport, and I was worrying about the exposure. We were shooting with chrome film, and it had to be right on or else it was worthless. It’s not like digital where you can be two stops off and fix it in post-production.

“I kept going, ‘Gosh, Peter, I don’t know if I got it–the light was this and so forth.’ He was pissed off because he knew that I had a better angle. He finally said, ‘Just shut up.’”

Beck’s photo was cropped to run as a vertical image on Sports Illustrated’s cover. Even in the crop, wisps of white netting, eerily out of focus, are faintly visible.

“That picture represents somebody who was in love with what they were doing.”

Chastain re-appeared on the cover of SI in December, along with her teammates, as the magazine’s “Sportswomen of the Year” (shot by fashion photographer Mark Abrahams). She would later be accused of turning the celebration into a look-at-me opportunity, an interpretation that she rejects. “What I explain to people is, imagine the moment you created as a kid in the playground many, many times–where you have the last shot and the clock is ticking down and the crowd goes wild,” she said. “Maybe in the playground you jump up in the air or pump your fists. But to do this in real life: the emotion and the energy and the electricity and the crowd–it was insanity because I wasn’t really in control. It was just a spontaneous expression to a wonderful moment, but a moment that was a lifetime in building.”

DiCicco concurs. “That was a response that a top player would do after scoring an incredibly important goal,” he said. “Brandi celebrated a goal in a way she had seen countless men celebrate big goals. In that moment I don’t think she felt anything other than exhilaration and relief.”

Chastain kept playing afterwards, professionally and for the national team, until the early 2000s. Then she retired and became a TV commentator. Now 46, she coaches boys’ high school soccer and is married to Jerry Smith, the women’s soccer coach at Santa Clara University.

The world’s most famous sports bra was briefly displayed at the Sports Museum of America in New York City. After the museum folded, it was returned to Chastain. It now hangs, framed, in her home next to the Sports Illustrated cover.

Chastain and Beck have since met and discussed the moment and the photograph. They even reprised the scene about 10 years later on a soccer field in northern California, with Chastain ripping off her top and a bunch of 10-year-olds running up behind her. “That was pretty cool,” she said.

It’s worth noting that the U.S. has not won another World Cup since 1999. (Talk about your SI cover jinx!) Indeed, that drought has installed Chastain and her teammates in legend. They’ve been the subject of two documentaries—Dare to Dream in 2005 (HBO) and The 99ers in 2013 (part of ESPN’s Nine for IX series)—and, frankly, continue to overshadow the teams that have followed them.

It’s also worth noting that the long-term goal of many players on the team (including Chastain)—the establishment of a prominent professional soccer league—has proven elusive. Several attempts, including the Women’s United Soccer Association and Women’s Professional Soccer, faltered. The nascent National Women’s Soccer League receives very little media coverage. (China just launched its own professional women’s soccer league.)

And, in an unfortunate reminder that women’s sports are still considered second-tier, the national team and their opponents are playing this year’s World Cup on artificial turf, not natural grass, despite player protests and a threatened lawsuit. DiCicco will provide commentary during the tourney for Fox Sports. (Todd Curran is the head coach of the women’s soccer team at San Diego Mesa College.)

Beck himself encountered a professional reversal on the eve of this year’s Super Bowl. In a cost-cutting move, Sports Illustrated laid off the magazine’s entire division of staff photographers: Beck and five others—Simon Bruty, Bill Frakes, David Klutho, John McDonough, and Al Tielemans—lost their jobs. SI continues to hire them, but as freelancers.

“It was like these corporate bean-counters said, ‘Get rid of them,’ to save some money,” he said. “There was no montage highlighting our work. I’m not sure if anyone really cares.”

His image of Brandi Chastain, triumphant on a sweltering July day in Pasadena, will endure, documenting a populist victory that helped propel women’s soccer into the national consciousness.

That legacy, Chastain believes, is crucial. “I think, mostly, young girls demur when they do something great,” she said. “They don’t want to hurt anyone’s feelings or apologize for their greatness. I feel that picture represents somebody who was in love with what they were doing and joyful at the outcome. We must as women and girls celebrate the good things that we do because if we can’t feel good about the good things we do, nobody else can.”

David Davis is the author of Waterman: The Life and Times of Duke Kahanamoku (Univ. of Nebraska Press), to be published on Oct. 1.