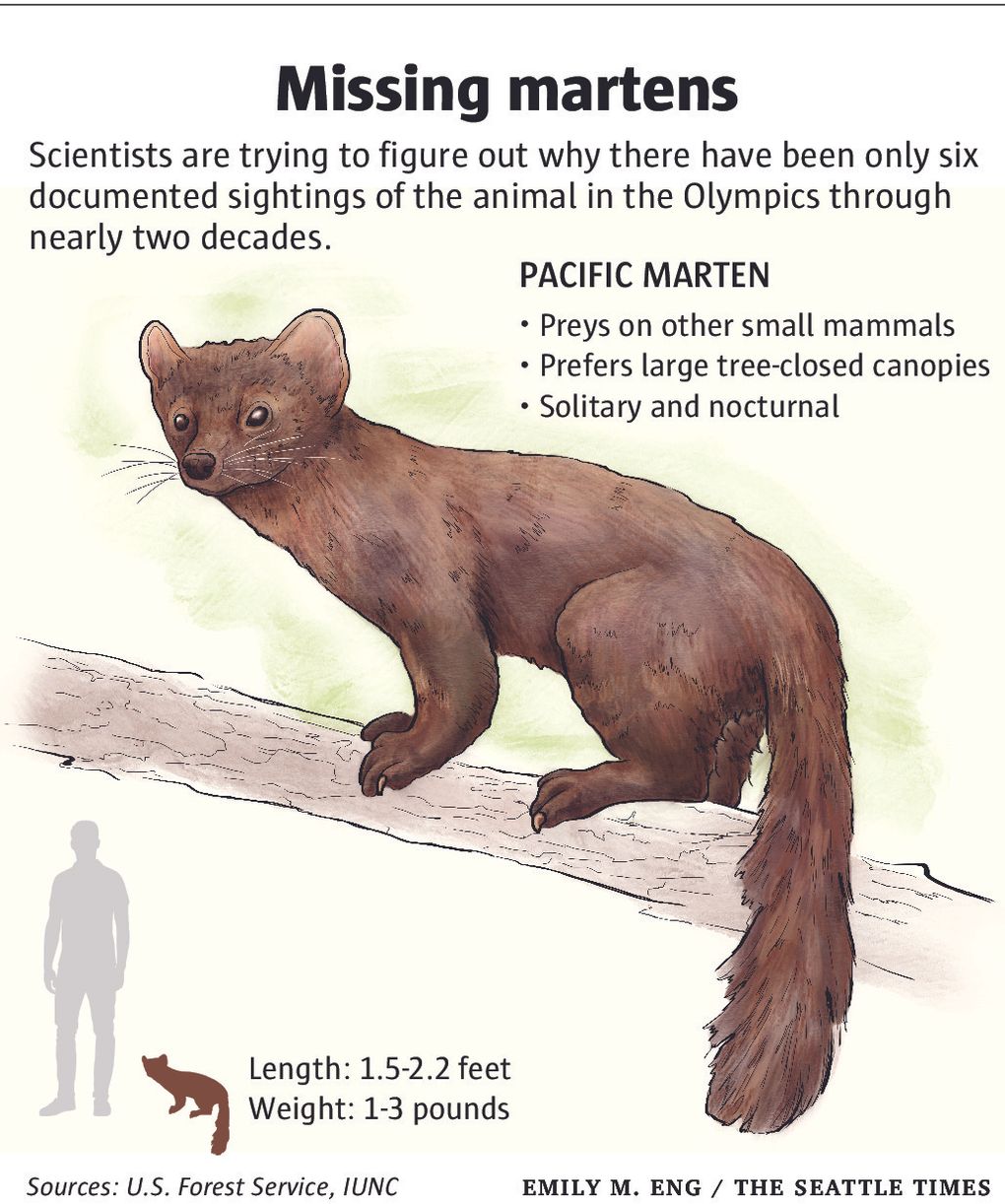

MOUNT SKOKOMISH WILDERNESS, Olympic National Forest — Once common here, martens — sleek, bright-eyed mammals less than half the weight of a small house cat — appear to have virtually disappeared from their mountain redoubts.

Or have they? Scientists are trying to find out what is going on with the elusive native of these mountain forests, and why.

In the past 16 years, in remote camera surveys in which hundreds of thousands of images of animals were snapped by wildlife cameras all over the Olympics, only two stations caught a photo of a marten.

In all, only six documented sightings of the animal have been recorded since 1988 from all sources — including photos by hikers and the find of a carcass.

Betsy Howell, a wildlife biologist with the U.S. Forest Service, is working with a host of agency and nonprofit partners to look for answers. So on a recent glorious fall morning, she and two other researchers packed their gear and headed up the Mount Rose Trail.

Their quest: checking two new wildlife cameras perched high above Lake Cushman, in the old-growth forests that reign supreme in this mountain wilderness. For it seemed if Pacific martens were anywhere, they ought to be here, in this deep, roadless forest.

Howell and other researchers were deploying a new type of device, a scent lure that continually drips out a super-stinky attractant to keep its allure fresh, instead of dissipating in three or four months.

Next year, in addition to using the lure dispensers, Howell intends to try another innovation, joining with other researchers to document the presence of martens on the landscape using specially trained dogs seeking the scent of the target animals’ scat.

For the question of just what is going on with martens is a pressing one.

Martens are part of the balance of native animal life in the Olympics. Supremely adapted to deep snow, they are avid hunters of snowshoe hare in the winter, rocketing across deep drifts after their quarry. They also are masters of the subnivian world, searching out mice, voles and other tasty meals in their hideyholes under the snow.

Lithe and athletic, climbing a tree is nothing for them. The most rugged terrain of high-elevation Olympic slopes ragged with rock, blowdown and vegetation that would trip up even Sasquatch is no problem for their slinky, sure-footed ways.

Yet something appears to be amiss in their world.

Scientists on the trail

Martens are abundant in the Cascades, here, there, everywhere, just as they should be. Yet in the Olympics, researchers deployed nearly 200 wildlife cameras in 2016 in the coastal strip and high elevations of the Olympic National Park and National Forest, using remote cameras. They snapped nearly 400,000 images of animals of every sort.

Wildlife in general was marvelously abundant, with the cameras capturing moments in the lives of an Olympics menagerie: Bushy-tailed wood rats. Mountain lions. Black bear. Long-tailed weasels. Opossum. Northern flying squirrels, mice, birds, chipmunks, spotted skunks, short-tailed weasels, Douglas squirrel, snowshoe hare. And even fishers — recently reintroduced to the Olympic National Park — by the score.

But just one marten.

So it is that Robert Long, senior conservation scientist at the Woodland Park Zoo, who is working with Howell on the marten-tracking project, was up a tree recently, sticking his nose in the business end of one of the new scent lures.

He collaborated with Microsoft and the Idaho Department of Fish and Game to develop the continuously stinky lure, knowing that winter was the best time to capture images of denizens of the deep snow — the very time it’s most difficult for researchers to re-bait a camera station. “It’s been a game changer,” Long said of the new method, in use now for two winters. “Our wolverine detections have skyrocketed.”

In collaboration with the Forest Service and other agencies, he mounted two of the lures with cameras on Mount Rose last June, and this was his first look at just how they were doing. Job one was to make sure the scent lure was still excreting its powerful potion. His contorted expression, as he stuck his nose toward the lure, affirmed that all systems were still go.

Next he plucked the prize the researchers had huffed and puffed up here to get: a memory card in the digital camera, activated by heat and motion, holding all the images.

Long tossed the card down to Paula MacKay, an independent contractor working on the marten project, who loaded it into an iPad she toted up the mountain. Howell and MacKay eagerly crowded around the screen, scrolling and scrolling through 1,756 new photos.

“Wait! What do we have here!” said Howell, studying a grainy night shot. But alas, it was flying squirrel. “That looked hopeful for a minute,” Howell said. But no marten. Not even a flick of a tail.

A few theories

With a bit of deft climbing, Long next put in a fresh memory card, big enough to carry the camera through a long winter, predicted to be snowy. The probability of detecting a marten goes up along with the snowpack.

But will it? Washington is predicted to, in general, get less snow and more rain in the future because of climate change, and the state already experienced a snow drought in the Olympics in 2015.

One of the possible problems challenging the Pacific marten in the Olympics is climate change, with snowpack cratering to zero in the Olympics in 2015. Martens need deep snow for their winter hunting success, and count on their fleet feet in snow to evade predators. That’s an advantage they lose without the extreme snow at high elevation they are so perfectly adapted to.

While the Cascades face a similar challenge, “something different is going on in the Olympics,” Howell said.

Other theories are in the works. Could it be disease? Or perhaps predation by other animals, such as coyotes? Fishers are back, true, but the marten’s decline on the peninsula predates their return, Howell noted.

Another possibility is that logging outside the wilderness and park has stripped too much of the complex habitat martens require, or that they have yet to rebound from over-trapping. Living as they do in the Olympics, the island effect of their habitat can strand small populations with fewer new recruits to diversify and build up populations.

For now, the marten mystery is attracting more attention over the absence of a spirit of the Olympics.

“I feel there is importance to bearing witness to loss; we know something is happening,” MacKay said. “Why is it happening? There are more layers these questions allow us to get to.”