Happy Sunday! Welcome to Holy Shift, where we highlight big innovations in the auto and racing industries each week—whether they be necessary or simply for comfort.

In the days leading up to the 1987 Winston 500 at Talladega Superspeedway, now-NASCAR Hall of Fame driver Bill Elliott set the all-time series qualifying speed at 212.809 mph around the 2.5-mile monster of a speedway. Nearly three decades later, that record remains at the top of the list.

It’s not because Elliott had a special route around the track or anything. It’s because NASCAR made the cars slower.

The sanctioning body did so with the famed restrictor plate, which limits air flow into the engine and reduces horsepower. When the now-retired Jeff Gordon sat on pole in the most recent Talladega race in October, his lap time hovered at 194.5 mph. That’s nearly 2o mph slower than was the norm in Elliott’s day, but NASCAR put a stop to it the very weekend Elliott set that still-standing record.

For an enclosed circuit, speeds surpassing 210 mph were dangerously high. According to ESPN, Talladega was “the fastest enclosed racetrack in the world” at the time. The headlines looked good, too—Elliott’s time was just under the 216.609 mph set by Bobby Rahal in Indianapolis 500 qualifying that year.

But NASCAR wouldn’t rival those speeds again, as 1987 marked the final year that the series ran Daytona International Speedway or Talladega Superspeedway without a restrictor plate. The event that ushered in a slower version of NASCAR superspeedway racing featured an airborne Bobby Allison, whose car destroyed nearly 100 feet of the catch fence but managed to stay within the track.

Here’s the incident that introduced a need for a plate:

No deaths occurred as a result of the wreck, though ESPN reports numerous injuries occurred—one woman reportedly lost an eye in the whole deal.

Even nearly 30 years later, Allison’s recount of the event sends chills. From USA Today, who caught up with Allison after an ugly 2013 Xfinity Series wreck at Daytona International Speedway:

“In the ambulance, I said, ‘How many people got hurt [in the 1987 wreck]?’ “ Allison recalled Sunday. “They said, ‘Nobody got hurt.’ They put me in the safety vehicle and headed around the racetrack the long way to get back to the infield hospital. I said, ‘Yeah, they’re taking me this way so I don’t have to see all the dead bodies laying there.’ They really had me worried.

“We got back to the infield care center, and the doctor came out and said, ‘Shut off the helicopters – we don’t need ‘em.’ And I said, ‘If they don’t need the helicopters, that means nobody is hurt bad.’ It gave me some relief.”

The scene of the wreck invoked a bad feeling for more than just Allison. NASCAR acted quickly, formulating a new system for its two fastest speedways—both Daytona and Talladega.

NASCAR’s first attempt at slowing the cars down consisted of mandating a smaller carburetor in Daytona Beach in July 1987, just a few months after the Allison wreck. It didn’t go over well. From Road and Track:

Teams didn’t like it, most likely because it reduced performance in areas other than top speed. It took a season to reach consensus, but when the green flag dropped on the 1988 Daytona 500, every car had a restrictor plate bolted to the intake.

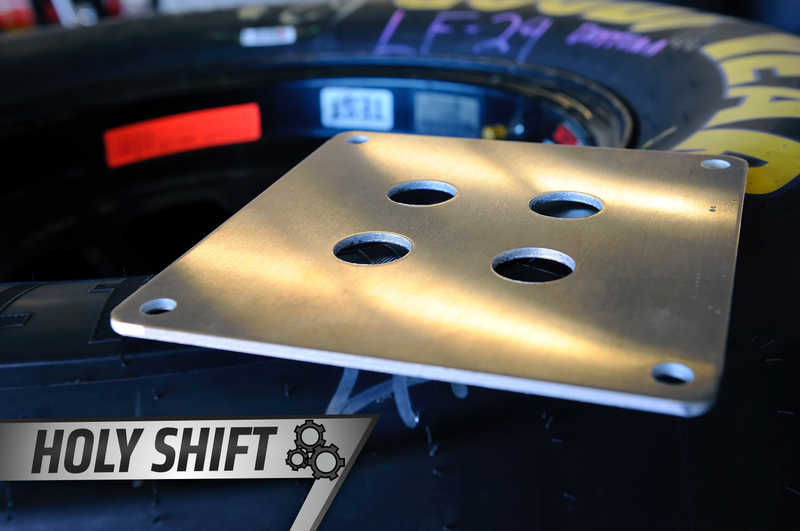

The restrictor plate limits air intake—and speed—to the engine by means of four holes in a metal plate, which vary in size depending on track conditions. “Mandate” isn’t used lightly in this case, either—NASCAR passes out the plates to its teams as they go through technical inspection.

Even with the choke on air intake and slower speeds, a few wrecks resembling Allison’s plagued recent years at Daytona and Talladega. The aforementioned wreck that injured 28 spectators came when Kyle Larson went airborne on the last lap at Daytona in 2013, and an infamous 2009 wreck at Talladega involved Carl Edwards sailing through the air and into the fence as well.

The restrictor-plate system isn’t perfect, and wrecks at Daytona and Talladega still make it into the catch fence occasionally. But, a 194-mph airborne race car is slightly more comforting than one with an average speed of 20 mph faster.

If you have suggestions for future innovations to be featured on Holy Shift—in street cars, the racing industry or whatever you’d like—feel free to send an email to the address below or leave them in the comments section. The topic range is broad, so don’t hesitate with your ideas.

Photo credit: Jared C. Tilton/Stringer/Getty Images