If you were looking to create an object that was the perfect physical manifestation of the Summer Olympics’ contradictory relationship with the partially invented history they sprang from, you could do a lot worse than the Olympic Torch.

Every four years, the Olympic Torch begins its journey to the host city from Olympia, Greece. The torch’s flame symbolizes Prometheus stealing fire from Zeus, and it’s lit with a parabolic mirror so as to align with Ancient Greek technology. Nothing could harken back to Greek Antiquity better than a famous Greek myth made real, but the Olympic Torch is not an ancient tradition. The IOC only started lighting symbolic fires in 1928, and the torch made its debut in 1936 Berlin Games. You know, the games that were hosted by Adolf Hitler’s Nazi Germany.

The opening ceremony for this summer’s games in Rio will happen on Friday, and at some point during that ceremony or in the weeks that follow you will be fed some story about how the Olympics transcend politics and unite the citizens of the world, just as they have for thousands of years. The Games will be presented as the continuation of an ancient tradition, the unifying vision of the Greeks streamlined and augmented with current-day sports that didn’t exist thousands of years ago. This is not entirely accurate, and while there is some truth to the mythologized idea of an ancient and pure sporting competition, the modern Olympics don’t have a lot in common with the ancient games, which themselves were never all that apolitical. In fact, the Olympics we know today only exist because of a 19th century Frenchman’s anxiety over his country’s poor military record and a lucky archeological discovery.

The Ancient Olympics began sometime around 776 B.C. and lasted until the late 4th century A.D. They were, as historian Judith Swaddling notes, as much a religious festival as an athletic competition. As such, their origins trend towards the mythologic. One myth goes that Hercules created the land near Olympia that held the first Olympics and started training there as a tribute to Zeus. Another posits that an ancient Greek king asked the Oracle of Delphi how to put an end to wars across Greece, and she recommended that he call for an Olympic truce while staging the games. These myths are just that, but most histories of the Games stress how central religion was (the official Olympics website has a section about the characters of Greek mythology). When Emperor Theodosius banned the Games in the 4th century, he did so as a way to eradicate “pagan cults.”

Religion’s apocryphal role aside, the Olympic truce did help contribute to the early unification of Greece, and militarism is one of the through lines from the ancient Olympics to the modern version. The only events at the first few games were foot races, and eventually they were joined by other war-adjacent sports, like wrestling, boxing, and equestrian. While the Olympics did help put a stop to wars around Greece, they were not apolitical, as they are often are portrayed. Spartan athletes were banned from the 424 B.C. games because of the Peloponnesian War. In 364 B.C., soldiers from nearby Elis attacked the Olympics. Athletes were also often bribed by rival states to lose or otherwise guarantee positive outcomes, because winning at the Olympics was a proxy for military dominance.

That idea was at the heart of the Olympics’ resurrection campaign hundreds of years later, after the site of the Ancient Games was destroyed in a pair of sixth-century earthquakes. After about 200 years of failed plans and misdrawn maps failed to turn up Olympia, English theologian Richard Chandler stumbled upon the ruins of Olympia in 1766 “almost by chance.” The Germans eventually excavated the site in 1875, and reports from Greece eventually reached Pierre de Coubertin.

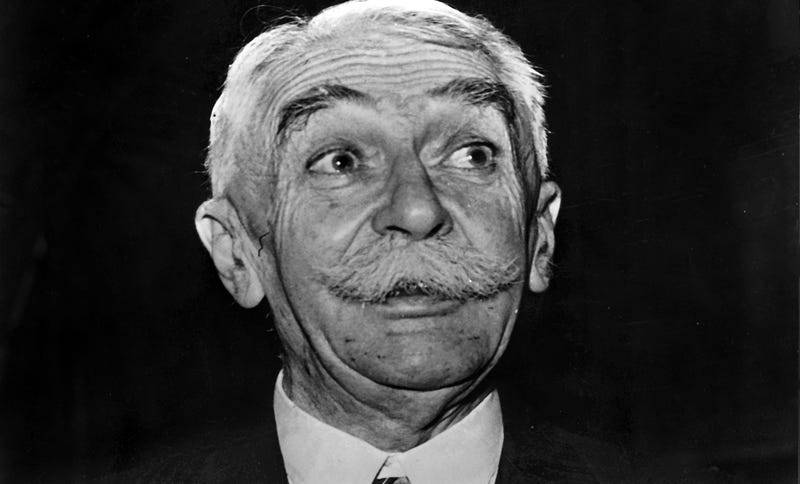

Baron Pierre de Coubertin was the descendant of French royalty, an aristocrat and intellectual during the late 19th century. That time was a particularly tumultuous one for France. The French Empire dissolved in 1871 after they lost the Franco-Prussian War, and a bunch of radical socialists seized Paris and established the Paris Commune as a direct result of Napoleon III’s emphatic failure in the war. Coubertin came up studying education and history during a time of particularly acute anxiety over France’s waning military power. While on a visit to England in 1882, Coubertin discovered rugby, and he credited the British Empire’s military might in part to their entrenched sports culture.

As Christopher Hill noted in “Olympic Politics,” Coubertin wasn’t particularly interested in internationalism, and he had no interest in cultivating the Olympics’ now-vaunted qualities as a unifier of nations and a place for disparate cultures to find common ground through sports. He was sick of France losing wars and his twin studies in ancient history and education led him to believe that the best way to promote social values and strengthen his country was to revive the Olympic Games. Coubertin romanticized the ideal of the Olympics, and certainly papered over some contradictions in his zeal to bring them back.

But he was, of course, eventually successful. After persuading the Zappos cousins, two rich Greek philanthropists, to help refurbish Panathinaiko Stadium, Athens held the first modern Olympic Games in 1896. There were 311 athletes, of which 230 were Greek. The Greeks wanted the Games to be held as they were in ancient times, in the same place every four years, but Coubertin convinced them to move them around. This proved to be a disaster, and the 1900 Paris Olympics and the 1904 St. Louis Olympics were both non-events, as they were competing with the World’s Fair in both years and were summarily ignored. Additionally, the possible presence of German athletes apparently angered the French delegation, and were it not for Coubertin’s influence, the animosity between the two nations might have torn the Olympics apart.

The Olympics have never been the politics-free zone of international cooperation that their slick marketing makes them out to be. This is to say nothing of the Hitler Olympics, the 1972 massacre in Munich, or the time when the United States and USSR boycotted and counter-boycotted each other’s Olympics in the 80’s. In fact, the Olympics have always served as proxy conflicts between nations, and they’ve been so effective because of a particularly nationalist attachment to sports as evidence of a nation’s worth, which has been at the heart of the Games since well before Coubertin, even if he believed in an extreme version of it.

So don’t feel bad if you find yourself cursing a Russian gymnast or an Italian handball player as you watch the games unfold this month. Don’t be alarmed if you taste the sour bile of nationalism on the back of your tongue, because that taste is what the Olympics have always been about.