The number of truly iconic hockey pictures is surprisingly small. The sport is notoriously difficult to photograph, thanks to the fast-paced action, the elusive puck, and some unique space, proximity, and lighting restrictions. There’s Denis Brodeur (yes, Martin’s father) and his shot of Paul Henderson celebrating Team Canada’s victory in the 1972 Summit Series; Ralph Morse’s eerie portrait of goaltender Terry Sawchuk, his scars and stitches simulated with makeup; Heinz Kluetmeier‘s “Miracle on Ice” celebration photo after the U.S. defeated the U.S.S.R. at the 1980 Olympics.

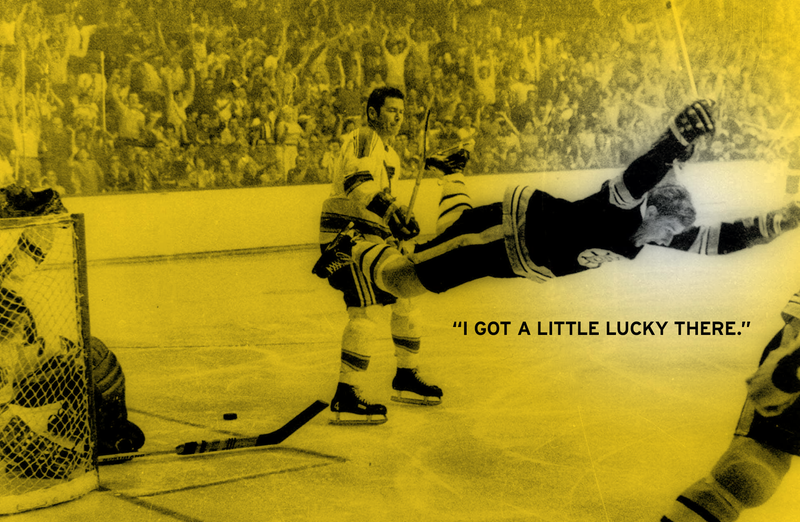

But one image looms above the rest: Ray Lussier’s photograph of Bobby Orr immediately after he scored the Stanley Cup-winning goal for the Boston Bruins in Game 4 of the 1970 Finals. The black-and-white image shows Orr in mid-air, hovering above the ice, as all of Boston Garden—all of New England—erupts.

At the time, Lussier was a staff photographer for the Boston Record American newspaper. That he was in the right place at the right time to snap the photo, he later said, combined a lot of hustle, no small amount of luck, and a lifelong passion for hockey.

“You have to know and love a sport to get peak action shots,” Lussier once said. “My [love] is ice hockey.”

It would be inaccurate to say that the city of Boston was starved for a winner in 1970, not with the Celtics’ dynastic run of 10 NBA titles in 11 seasons (1959-1969). But the Red Sox hadn’t won the World Series since 1918, and the then-Boston Patriots—“a vaudevillian one-liner” at the time, according to longtime local journalist Kevin Paul Dupont—had just one playoff appearance in 10 AFL seasons.

The beloved Bruins had not lifted the Stanley Cup since 1941, back when Dit Clapper was steadying the blue line. They’d missed the playoffs eight straight years, from 1959 to 1967, despite the fact that there were only six teams in the NHL and, of those, only two did not qualify for the postseason.

Bruins fans of that era, an eclectic crew comprising Harvard professors and Southies alike, stayed loyal throughout the drought. Photographer Stanley Forman, who worked with Lussier at the Record American, can still remember the location of his season tickets from years ago—“Section 73, Row C, Seats 3 and 4”—as well as the official seating capacity for hockey games at Boston Garden: “13,909.”

In the fall of 1966, salvation for the long-suffering Gallery Gods came to Causeway Street. Bobby Orr was 18, hailed from Parry Sound, Ontario, and arrived with a godawful buzz cut. Before he came along, defensemen rarely ventured past the blue line to join the attack. Orr revolutionized the position, ignited a city, and carried a black-and-white league into technicolor.

“He was God,” said Forman, who witnessed every game Orr played at Boston Garden. “When he was on the ice you just watched him.”

“You couldn’t get tickets unless you knew somebody,” said Richard Johnson, curator of The Sports Museum, located in the Bruins’ present-day home of TD Garden. “It was like getting tickets to a Beatles concert.”

The Bruins reloaded around Orr, thanks to a blockbuster trade with the Chicago Blackhawks that netted Phil Esposito, Ken Hodge, and Fred Stanfield to complement veterans John Bucyk and John McKenzie and flashy center Derek Sanderson. Gerry Cheevers and Eddie Johnston capably held down the goalkeeping duties.

Meanwhile, the NHL was embracing expansion, doubling the size of the league in 1967. The “Original Six” (Boston, Montreal, Toronto, New York, Chicago, and Detroit) were grouped in the East Division, with the new franchises (St. Louis, Pittsburgh, Minnesota, Philadelphia, Los Angeles, and Oakland) placed in the West.

The arrangement led to an oddity: An expansion team, the St. Louis Blues, was able to advance to the Stanley Cup Finals in each of the first three years of its existence.

In 1968 and 1969, the Blues were swept by the Canadiens. In 1970, they drew Orr and the Bruins.

Ray Lussier (pronounced Loo-see-AY) was raised in a tenement house in the French-Canadian community of Lawrence, Mass. He took whatever jobs he could find during his childhood—delivering papers, setting up pins in a bowling alley—to help out his family.

He had little time for games, but he played hockey whenever he could. His love of the sport, he later said, informed how he approached it with a camera: Anticipation mattered as much as reflexes. Hockey is “a game of quick, constant action,” he remarked. “Even when it’s fast you have to know how to wait for the sudden turns, switches and scrambles.”

Lussier became interested in photography when he was 12, when his father scraped together the money to buy him his first camera. He installed a tiny darkroom in his closet and made prints from old negatives. After graduating from high school, Lussier enrolled in the Franklin Technical Institute of Photography in Boston.

His first full-time photojournalism job was with the Haverhill Journal in 1958. He shot everything: fires and murders, music recitals, high school sports. Ray was “always the one to make a story jump with his art,” according to fellow Journal reporter Russ Conway.

After the paper folded in the mid-’60s, Lussier joined the Boston Record American. “We were a tabloid, so we were the picture paper,” said Forman. “Our major competition was the Globe, because they had more photographers, so we always wanted to beat the Globe.”

In May of 1970, with the Bruins in the Stanley Cup Finals for the first time since the Roosevelt administration, Hub newspapers covered every second of every period of every contest, especially after Boston won the first two games in St. Louis. They returned home and whipped the Blues, 4-1 to take a commanding 3-0 series lead.

On May 10, Record American sports editor Sam Cohen sent Lussier and a small squadron of photographers and reporters to Boston Garden for Game 4. They expected it to be little more than a coronation for the black and gold.

The temperature that Sunday (which happened to be Mother’s Day) was unseasonably warm, in the 90s. Inside the arena, without air conditioning, it was stifling.

The teams traded goals and were deadlocked at 2-2 after two periods. The Blues regained the lead 19 seconds into the third before John Bucyk knotted the score with about six minutes left. Regulation ended in a 3-3 draw, bringing on sudden-death overtime.

Lussier, with his Nikon F with a 35mm lens, was stationed at the east end of the arena, near the goal that Cheevers was preparing to defend. But he “just knew the Bruins were going to win the thing in OT,” he later told Russ Conway, so he decided to venture toward the other net, where the stakes were higher.

“Ray knew that if St. Louis scored in overtime, it wouldn’t really mean anything,” Forman said. “It would be 3-1 in the series. But if the Bruins scored, they’d win the Cup. Ray was smart enough to know that and to put himself in the right place.”

While the Zamboni resurfaced the ice, Lussier snuck in through the door at the opposite end of the building. He saw an empty “shooting hole” cut into the protective glass near the Blues’ goal and nabbed it. This space was assigned to a Globe photographer, who’d apparently vacated the spot to slake his thirst with a soda or a beer (depending on which account you believe). Lussier protected his fellow lensman by never publicly revealing his name.

Lussier was now perfectly positioned for a Bruins attack. His instincts proved correct. Boston coach Harry Sinden sent out the checking line of Sanderson-Westfall-Carleton to start the overtime, as well as Orr and fellow defenseman Don Awrey, and they dominated from the faceoff.

Under attack, the Blues tried to clear the zone. Orr anticipated the play from the right point and, pinching in, gained control of the puck near the face-off circle to the left of goalie Glenn Hall.

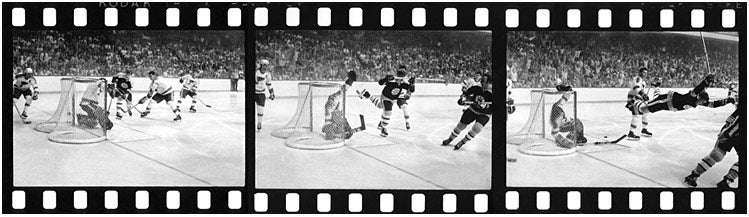

In a series of moves almost too rapid for CBS’s cameras to track, Orr fed Derek Sanderson behind the net, darted toward the goal between two opponents, corralled the return pass by the goalmouth, re-directed the puck between Hall’s legs, began to raise his stick in his celebration, and then found himself airborne after Blues defenseman Noel Picard’s stick caught him around the left ankle.

All of 40 seconds of overtime had elapsed.

“If [the puck] had gone by me, it’s a two-on-one,” Orr said years later. “So I got a little lucky there, but Derek gave me a great pass and . . . Glenn had to move across the crease and had to open his pads a little. I was really trying to get the puck on net, and I did. As I went across, Glenn’s legs opened.”

“I didn’t think he’d go five-hole,” Hall recalled thinking.

“I looked back,” Orr said, “and I saw it go in, so I jumped.” Orr’s expression was one of pure glee as he levitated three feet above the ice, arms outstretched, After he landed and slid to a halt, Wayne Carleton jumped on top of him, followed by the rest of the Bruins.

Lussier kept shooting as the play unfolded, using his motor drive to snap several pictures in sequence. “I thought I had something good,” he later admitted.

With the arena shaking in ecstasy, the wayward Globe photographer returned to find Lussier in his place.

“What are you doing here?” he said.

“Oh, I’m sorry,” Lussier replied. “I got what I needed. It’s all yours.”

Shooting hockey in the pre-digital era was no easy thing, in part because the lighting inside those old arenas was so inconsistent. Every arena used different locations for their overhead lights, making it difficult for photographers to get their settings just right, even within the same building. At certain angles, the ice acted like a giant reflector, turning players into silhouettes. Back then, only the heavy hitters like Sports Illustrated could afford the expense of installing strobe lights above the ice, which acted like a giant camera flash—the Record American certainly didn’t use them. Lussier thought he had a good shot, but he wouldn’t know for sure until he saw the negatives for himself.

With the celebration still going on, Lussier exited the arena. He raced back to his office, hustled into the darkroom, and developed the 35-millimeter film in the chemical soup.

“Ray said, ‘come with me,’” Forman recalled, and then shared the strip of photos with the Orr sequence. Lussier was doubly proud: he’d gotten the shot and trumped the Globe.

Surprisingly, the “Flying Bobby” photo was not published in Monday’s edition of the Record American. Instead, the paper led with Mike Anderson’s picture of Orr drinking champagne out of the Stanley Cup.

“Sam Cohen was a genius sports editor,” Forman said. “He wanted to save Ray’s photo for the next day’s paper. He goes, ‘Print it big!’”

On Tuesday, May 12, Lussier’s photo appeared for the first time—and it ran big. The horizontal image was published as a double-truck—that is, across two pages—in the centerspread of the newspaper.

The headline above the photo read: “Orr’s Goal That Won Stanley Cup—Greatest Hockey Photo Ever.” In small type beneath the picture was Ray Lussier’s name.

According to hockey historian Andrew Podnieks, author of The Goal: Bobby Orr and the Most Famous Goal in NHL Stanley Cup History, Lussier was not alone in capturing the moment. The Globe’s front page featured Frank O’Brien’s picture of the goal, taken from upstairs.

Fred Keenan of the Quincy Patriot Ledger photographed the Orr sequence from a similar vantage point as Lussier’s; the two were probably standing next to each other. Clearly visible behind the net are Sanderson, his arms raised after his assist, and dejected Blues defenseman Jean-Guy Talbot. Carleton’s celebration and Orr’s stick fit completely in the frame.

Lussier’s shot, on the other hand, does not show Sanderson or Talbot. Much of Orr’s stick cannot be seen. And, the partial view of Carleton’s leg and referee Bruce Hood’s arm (far right) is confusing to the eye. Keenan’s “Flying Bobby” shot is actually superior in composition.

But while Keenan captured Orr as he attained lift-off, Lussier captured Orr flat-out horizontal. That slight discrepancy—perhaps a tenth-of-a-second difference in timing—resulted in a more dramatic and engaging montage, with Orr’s victorious exuberance juxtaposed against Picard’s anguish and Hall’s twisted, beaten form.

“The Lussier shot came out and then everyone wanted that and no other, so all others were quickly forgotten,” photographer Al Ruelle told Podnieks.

Indeed, Lussier’s photo of Orr could soon be found in more bars and homes in Massachusetts than portraits of John F. Kennedy. “You saw it everywhere afterwards,” said Johnson, curator of The Sports Museum. “It compares with [Carlton] Fisk at the 1975 World Series, willing the ball fair. But today people remember the video of Fisk [from the NBC-TV broadcast], whereas with Orr’s goal it’s the still photograph. It is an image whose brilliance both captures and reflects upon the genius of its subject.”

“Nothing compares,” said Phil Castinetti, owner of the Sportsworld memorabilia store in Saugus, Mass. “Not the Fisk photo, not ‘Havlicek stole the ball,’ not Vinatieri kicking the field goal to send the Patriots to the Super Bowl.”

“It’s the perfect picture,” Forman said. “It turned Bobby Orr into a legend. He was the toast of the town.”

He was also the toast of the NHL. Just 22, Orr swept just about every award the league gave out: the Hart (MVP), the Norris (best defenseman), the Ross (most points), and the Conn Smythe (playoff MVP). In December, Sports Illustrated named him “Sportsman of the Year.”

In the accompanying profile, author Jack Olsen called Orr “the greatest player ever to don skates,” and noted, “To comprehend what it means to be the best both defensively and offensively in the brutal game of ice hockey, the fan must imagine a combination of Dick Butkus and Leroy Kelly, of Boog Powell and Bob Gibson, of Bill Russell and Oscar Robertson. Because of Orr, there are fewer arguments in the big hockey towns about ‘the good old days.’ He has brought a sheen to every skater, a gloss to the whole league and the whole sport.”

With Orr leading the way, the Bruins again won the Stanley Cup in 1972. But the magic didn’t last. Hobbled by a series of injuries and operations, Orr dynamic, dominating form slipped and he never regained it. Instead of launching a dynasty that could have rivaled the Celtics’, the Bruins were overrun by the Canadiens and the Flyers. (The Blues haven’t even made it back to the Finals.)

Orr retired in 1978, at the age of 30 and wearing a Blackhawks uniform. By then, thanks in no small part to his star power (as well as competition from a rival league, the World Hockey Association), the NHL had continued to expand. “From Orr’s first season to the time he retired, the NHL tripled in size, from six teams to 18,” Johnson said. “He put money in everybody’s pocket and made the NHL a must-see league.”

It was Lussier’s photo that burnished the legend of Number Four, and Orr has signed (and continues to sign) so many copies of the picture that the two became casual friends. Orr gifted Lussier two autographed hockey sticks that Lussier gave to two of his sons. (They eventually destroyed them playing pickup games.) When the Bruins held a 20th anniversary reunion for the 1969-1970 team, Orr made sure that Ray and his wife Claire were invited.

The world’s greatest hockey player and the general-assignment lensman bonded over what the photograph—one solitary image, frozen in time—meant to both their lives. It was the defining moment of Orr’s career; it was the pinnacle of Lussier’s.

Ray was always proudest of his professionalism. He had placed himself in the best possible location to get the image so that, when the opportunity arose, he was primed for it. And, of course, like Orr, he didn’t miss.

In 1979, Lussier (along with Stanley Forman) were part of the effort that earned the Record American’s photography staff the Pulitzer for team coverage of the blizzard of 1978. Not long after that, health issues forced Lussier to leave photojournalism.

To help pay the bills, he sold the copyright to the strip of Orr photos to Dennis Brearley, a former colleague who opened a gallery and memorabilia business devoted to historic New England images. The Brearley Collection is no longer in operation; the copyright was subsequently sold to a private buyer. (The local scuttlebutt is that Orr himself—or his representatives—purchased the rights to the sequence. Orr sells signed and framed photos of The Goal on his website.)

In 1991, at the age of 59, Lussier died from a heart attack. By then, his image was viewed as the most memorable photograph in NHL history. When Sports Illustrated ranked the 100 greatest sports photos of all time (a list that skewed heavily toward the magazine’s own work), Lussier’s was number 21.

The ultimate compliment came in 2010, when the Bruins commissioned a statue to honor Orr. Artist Harry Weber used Lussier’s photograph to create an enormous bronze monument outside TD Garden. Stick raised in triumph, the bronze “Flying Bobby” stands mere feet from the location of the now-demolished Boston Garden, where the flesh-and-blood Orr helped the NHL leap into the modern era.

David Davis (@Ddavisla) is the author of Waterman: The Life and Times of Duke Kahanamoku.