The attack began in the early morning hours of Sept. 5, 1972, when eight armed Palestinians affiliated with the Black September Organization snuck into the Olympic Village in Munich. They made their way to 31 Connollystrasse, where the Israeli delegation was housed, killed two men and took nine others hostage.

Television coverage of the standoff transfixed the world for 21 consecutive hours. Pre-9/11, this shocking and seminal moment introduced the modern age of terrorism to a global audience.

Today, the most enduring image from the Munich Massacre is the black-and-white photograph of a balaclava-wearing terrorist standing on the balcony at 31 Connollystrasse. He has been called “a masked figure of doom.” One reporter described his “hangman-like visage,” while another referred to “that specter with cut-out eyes.”

“The sight of a ski-masked terrorist peeking out from a white-paneled balcony amidst the long, tedious negotiations became a symbol of the times,” wrote former New York Times sports editor Neil Amdur, who covered the Games for the Times in 1972. It is “framed to the world’s soul, the last splice to the politics-and-sports-don’t-mix axiom.”

Several photographers took pictures of the masked man. And yet no English-language caption that has accompanied these photos over the past 45 years has identified him, either by name or alias. That’s a mystifying oversight given that there were only eight terrorists in Munich, all of whose names are well known. Faceless and nameless, his anonymity has become his identity.

I decided to try and find out the name of the masked man, if possible, beginning with the photographers who took the iconic picture. The most widely published photo is credited to Kurt Strumpf, a German photographer working for the Associated Press. His is the one you see in the countless books and films about Munich, primarily because many media outlets subscribed to AP’s popular wire service. But Strumpf died in 2014; efforts to speak with former colleagues in Germany were unsuccessful.

Another photojournalist, though—Russ McPhedran with the Sydney Morning News—took a photo that is eerily similar, but his work has been overshadowed by Strumpf’s iconic image. McPhedran, now 81, was happy to talk about that fateful day, and why the photo’s ambiguity guaranteed its immortality.

Russ McPhedran was born in Scotland and came to Australia with his family in 1950, when he was 14. He quickly found work as a copyboy at the Sun newspaper in Sydney. One of his first jobs took him to White City Stadium, where he helped out the paper’s staff photographers at the Davis Cup, which in the all-amateur, all-wooden-racquet, all-white-clothing era was the most prized tennis trophy outside of the Grand Slams. Australia and the United States enjoyed a fierce rivalry, meeting in the Davis Cup finals for 16 consecutive years, from 1938-1959, with an interruption for the war. The matches were a matter of considerable national pride.

As McPhedran ferried rolls of film from the stadium to the newspaper’s offices, he glimpsed a future. “I thought, ‘Those photographers actually get paid for doing this?’” he told me in a recent interview over Skype. “That’s when I decided: I want to be one of them.”

Someone at the Sun gave him a Graflex, the photojournalist’s camera of choice at that time, and he began accompanying the senior lensmen, shooting breaking news and sports alike, watching everything they did and learning the tricks of the craft: Never panic while working a big news story; always look after your gear; anticipate the action by “reading” the story in your mind even before showing up to the assignment.

Cameras didn’t have motor drives or automatic focus back then; photographers learned to edit as they shot—there was no sense wasting valuable film stock. Having quick reflexes was vital, as was an instinct for storytelling: the ability to take in the scene, artfully frame the most important elements, snap the picture, keep moving.

McPhedran absorbed the lessons well and soon moved up the ranks. “Having been on the staff of the Sydney Morning Herald for more than 30 years, I can honestly say Russ is the best photographer I ever worked with,” reporter Jim Webster told me. “He had a mind of his own, didn’t have to be directed at all and often he would see a story developing, take a picture and then tell the journalist about it.”

In search of more experience and exposure, McPhedran left Australia for a staff position at a paper in Hong Kong. Then off to Fleet Street, the center of print journalism in London, where he wrangled a job at the Daily Express, a formidable sheet for photojournalists. He covered major stories—the Profumo Affair, the Great Train Robbery—and learned more tricks from war photographer Terry Fincher.

“Terry and I were in a pack of photographers shooting [prime minister] Harold Macmillan,” McPhedran recalled. “We got back to the darkroom, and I had one photo and thought, ‘Great, I got him.’ Well, Terry had five! He had a camera that he took the main picture with and around his body he had four other cameras with different lenses all linked to the first one. When he took one snap he got five photos. I thought, ‘My god. I know nothing.’”

McPhedran returned down under in 1968 and immediately shot a prize-winning photo of the Buckingham’s department store fire. He also gained a new title: senior photographer at Fairfax Media, the owner of the Sun and the Sydney Morning Herald.

In the summer of 1972, Fairfax assigned McPhedran to go to England and cover The Ashes, the intensely competitive series of cricket matches between Australia and Britain. Cricket photographers are required to stand far from the action at venues like Lord’s and The Oval, either behind the boundary ropes or in the stands. So, McPhedran made sure to pack his longest lens: a 400-millimeter. He took plenty of Kodak Tri-X, the black-and-white film that all the pros used, and his Nikon F2 camera. He fashioned a portable darkroom inside a tent to develop the film and make prints of the best shots. Then, from inside the media truck that accompanied the journalists on the tour, McPhedran slipped the prints into a transmitter (which was like a fax machine for photos) to wire them back to Sydney.

McPhedran was scheduled to be away from home for about three months. He’d arranged to take a vacation in Spain with his wife, Shirley, after the tour concluded in mid-August. But as soon as Shirley arrived in England, Russ received instructions to go to West Germany.

The holiday was canceled, and Shirley returned to Sydney. McPhedran headed to Munich to cover his first Olympic Games – the first in Germany since 1936.

The context of the Munich Olympics can only be explained by what happened in Berlin and Garmisch-Partenkirchen (site of the winter games) 36 years prior. From the swastika flags that flew on every street corner to the banning of Jewish athletes from competition to the hiring of Leni Riefenstahl to direct the documentary film Olympia, Adolf Hitler sought to turn the 1936 Olympics into a propaganda showcase for Nazism and the Aryan race. “Hitler’s games” marked the moment when the Olympic Movement was irreversibly co-opted by politics.

Like Rome (1960) and Tokyo (1964), Munich organizers viewed the Olympics as an opportunity to burnish a new progressive image for West Germany. A dozen miles from the site of the Dachau concentration camp, organizers stressed unity and peace: They created the first official Olympic mascot (a cute dachshund named Waldi) and hired prominent artists like David Hockney and Jacob Lawrence to design festive posters. The motto was Die Heiteren Spiele, or “The Happy Games.”

As the 7,134 competitors gathered in Munich, they found an Olympic Village designed to encourage the intermingling of nations and races (although men and women stayed in separate dorms). It was a veritable wunderland that featured a disco, a miniature golf course, a giant outdoor chess set, plenty of food, and superb training facilities nearby.

In their efforts to redeem Germany’s reputation, Munich organizers relaxed security precautions. Officers patrolling the Olympic Village wielded walkie-talkies, not guns. There were no metal detectors or security cameras. If athletes blowing off steam at a local beer hall returned after dark, they easily scaled the six-foot chainlink fence that was left unmonitored.

The games themselves proved to be frustrating for American athletes and fans. There were certainly moments of glory, led by Mark Spitz, who churned his way to seven gold medals and a bestselling poster that highlighted his Marlboro Man mustache and stars-and-stripes Speedo. Frank Shorter became the first American to triumph in the Olympic marathon since the controversial race of 1908, and wrestler Dan Gable and boxer Sugar Ray Seales powered past Eastern Bloc opponents to win gold medals.

But disappointment reigned. America’s fastest sprinters, Eddie Hart and Rey Robinson, were disqualified for missing their quarterfinal heats for the 100 because their coach told them the wrong start times. Miler Jim Ryun tripped and fell in a preliminary, ending his illustrious amateur career. Swimmer Rick DeMont was stripped of his victory in the 400-meter freestyle after team doctors did not clear with the IOC the prescription medication that he took for his asthma. And, as would be revealed years later, East Germany’s state-sponsored doping program assured the success of their female athletes.

Most controversial of all, the U.S. basketball team saw its unbeaten streak of 63 games and seven straight Olympic gold medals shattered when the Soviet Union scored on a disputed last-second basket that the officials should not have allowed. (The game is the subject of the fine HBO documentary :03 From Gold.)

All of this was instantly and totally overshadowed by what began just after 4:00 a.m. on September 5.

Mere hours after Spitz secured his seventh gold medal and cemented his legacy as the greatest Jewish-American athlete since Sandy Koufax, a band of terrorists from the Palestinian nationalist group Black September approached the Olympic Village. They climbed over the fence surrounding the Village with help from some drunken athletes returning from a night of carousing. Once inside, the eight fedayeen converged on a four-story building at 31 Connollystrasse, the living quarters of the male athletes and coaches from Israel. (The street was named after James B. Connolly, the American triple-jumper who in 1896 earned the very first gold medal of the modern-day Olympics.)

Their surprise assault was brutally effective. By around 5:00 a.m., the terrorists had taken 11 Israelis hostage, killing one in the process and wounding another. (He would later die after being tortured.) The group’s leader, going by the codename Issa, issued a set of demands in exchange for the remaining nine: the release of 236 prisoners, mostly Palestinians held in Israeli jails, and safe passage to an Arab country.

The nonstop coverage that ensued was the first time that TV networks broadcast an act of terrorism, in real time, to an audience of hundreds of millions. That this played out at the Olympics, an ideal as much as an athletic competition, dedicated to bringing nations together peacefully, only added to the drama.

“The Olympics of Serenity have become the one thing the Germans didn’t want it to be,” intoned ABC host Jim McKay. “The Olympics of Terror.”

September 5th was supposed to be a slow day at Munich. The swimming action had concluded; Olga Korbut, Ludmilla Tourischeva and the gymnasts had packed up their leotards; track and field and the U.S. basketball team had scheduled rest days.

For Russ McPhedran, it was a chance to catch his breath. Covering Spitz and Australia’s Shane Gould, the Sydney teen whose heroics (five medals, three gold) were overshadowed by Spitz’s, had kept him busy at the Schwimmhalle aquatics center. He’d scored a major coup by getting a photo of the two stars together inside the Village.

Australia’s journalists had earlier deadlines than their American and European counterparts, so they were used to meeting early in the morning to discuss their assignments. At around 6:00 a.m., McPhedran was having breakfast in the media center with colleague Jim Webster when longtime Reuters correspondent Vernon Morgan approached them.

According to Webster, Morgan told them about a report that “shots had been fired” in the Village. McPhedran and Webster had not heard anything, but their news instincts kicked in and they quickly left the dining hall. While McPhedran collected his gear, Webster changed into a tracksuit. They hurried to the Village, about a kilometer away, with McPhedran falling behind because he was lugging all his equipment.

Security had tightened. Policemen stood guard along the length of the fence. Using his tracksuit, Webster was able to bluff his way into the Village by convincing a policeman that he was “an athlete returning from a morning run without his ID.”

McPhedran could not penetrate the cordon. But he whipped out his long lens from the cricket matches in England, and he used it to snap pictures of the scene developing inside the Village: German officials with walkie-talkies, groups of athletes huddling with security.

He raced back to the media center with barely enough time to make the press deadline back home. Earlier, McPhedran had arranged to use the facilities operated by the Associated Press. But at this early hour he found the second-floor offices locked tight. Nobody was around.

“I rang the big boss of AP,” McPhedran recalled, referring to photo editor Bob Wells, “and he wasn’t happy. I said, ‘Let me tell you what’s happening and what I’ve got.’ He said, ‘I’ll be there in five minutes.’ He came down, opened the darkroom, and, boom, boom, boom, I sent the photos back to Sydney.”

McPhedran said that he gave the AP staffers two of his own images to transmit to their bureaus (for which he received two bottles of Scotch) before running back to the Village. When he got there, “all hell had broken loose.”

The Olympics was now a breaking-news event. The AP’s own Kurt Strumpf was working under the direction of Horst Faas, a legendary German photographer who’d won a Pulitzer Prize for his combat images from Vietnam. Co Rentmeester, a former Olympic rower who’d covered the Watts Riots and the Vietnam War, was working for the Time & Life family, along with Rich Clarkson and Neil Leifer. (It’s not clear whether Leni Riefenstahl, then 70 years old and credentialed for the U.K.’s Sunday Times, also photographed the terrorist attack.)

They were all on a grassy slope outside the fence; they employed anything handy — including stepladders — to obtain a good shooting angle into the Village and of the apartment building, which was about a quarter mile from their position.

“There was a view [toward 31 Connollystrasse] from a very near hillside and the press corps assembled there — perhaps 15 of us who found that viewpoint,” Clarkson said. “It was witnessing history, and we all knew it.”

McPhedran recalled being “very envious” because the other photographers had “the top of the range equipment, while I’m working for some pissy paper with very ordinary gear.”

He again employed his 400-millimeter lens, the longest he owned, and then screwed on a double-adapter that extended its range to 800mm. He added a single adapter, and that extended the focal length to about 1000mm. He used a tripod because, he admitted, “I was shaking like a leaf.”

It was unclear at that point how many terrorists were holed up inside 31 Connollystrasse. The photographers focused on Issa, their leader, who often emerged from the apartment to negotiate with German officials. He wore sunglasses, a tailored safari-like suit, and a white fedora. The rest of his face was painted black. (Issa was later identified as Luttif Afif, born in Nazareth to a Christian father and Jewish mother. Before the attack, he had lived in West Germany for 14 years and was engaged to a German woman.) Another terrorist, identified as “Tony,” wore a cowboy hat and was glimpsed occasionally with a machine gun.

And then, from the balcony doorway came another man. He was slender and wore a pale-yellow turtleneck sweater. A balaclava obscured his face except for two circular cutouts for his eyes and a horizontal slit for his mouth. He strolled along the balcony and took in the scene below.

McPhedran was too far away to distinguish much more than the man’s upper torso. But he trained his camera on the distant balcony and triggered several shots, making sure to advance the film after each one, before the man retreated inside the apartment. He’d been outside for no more than 30 seconds.

Again, McPhedran sprinted back to the media center. He said he had “the flutters” while processing the film. “We never knew what we had until we went into the darkroom.”

What emerged was a shadowy figure bent somewhat at the waist as he peered over the balcony. Of his face behind the mask, only the blacked-out skin around his left eye is visible.

McPhedran said he knew immediately that the photo of the terrorist conveyed “a menacing blankness.” He transmitted the image to Australia before returning to the Village. Meanwhile, AP was distributing Strumpf’s similar photo to its many bureaus around the world, and the Time & Life photographers were sending their versions back to the states. (Co Rentmeester’s version can be seen here.)

As the standoff at 31 Connollystrasse continued, the scene outside turned surreal. IOC czar Avery Brundage initially decided not to halt the Games, so cheers from events at nearby venues reverberated inside the Village gates. Athletes sunned themselves and played ping pong. Outside the fence hawkers sold ice cream and sausages.

McPhedran never left the scene except to wire home additional photos. “Anything fresh I got—the policemen on the roof—I transmitted,” he said. “I was just shooting.” His vigil lasted until darkness enveloped the village.

Eventually, Issa demanded a plane to fly the hostages to Egypt. German authorities schemed to ambush the terrorists at Fürstenfeldbruck air base and rescue the hostages, and arranged for helicopters to transport the hostages and kidnappers from the Village.

Initial media reports indicated that the police had succeeded, with all the Israelis saved. But the woefully unprepared and under-equipped Germans had bungled the mission. The remaining nine hostages died at Fürstenfeldbruck, murdered by the terrorists with machine guns and a grenade. One policeman was killed.

Jim McKay, on the air for ABC, got the official word of the disaster at 3:24 a.m. local time—primetime back in the United States—and delivered the news.

“When I was a kid,” a visibly anguished McKay said, “my father used to say our greatest hopes and our worst fears are seldom realized. Our worst fears have been realized tonight. They’ve now said that there were 11 hostages. Two were killed in their rooms yesterday morning, nine were killed at the airport tonight. They’re all gone.”

Five of the eight Black Septemberists died in the shootout, including Issa and Tony. The three surviving terrorists were taken into custody; they were freed just eight weeks later after Black September sympathizers hijacked a Lufthansa plane and demanded their release. (One of the terrorists is believed to be alive today; the other two were allegedly hunted down and killed by Mossad, along with the plotters of the attack.)

The next day the IOC held a memorial service for the slain Israeli athletes and coaches. Brundage, who had supported Hitler’s Olympic efforts in 1936 and helped convince the American public and media that the United States should not boycott Berlin, refused to halt the proceedings. “The Games must go on,” he thundered, a true believer in the Olympic ideal to the bitter end.

Many applauded Brundage’s decision to not let the terrorists control the fate of the Olympics (and thus allow those athletes who had not yet competed to have their chances). Others felt that continuing the Games in the wake of the tragedy was a travesty.

Wrote Jim Murray in the Los Angeles Times: “Incredibly, they’re going on with [the Games]. It’s like having a dance at Dachau.”

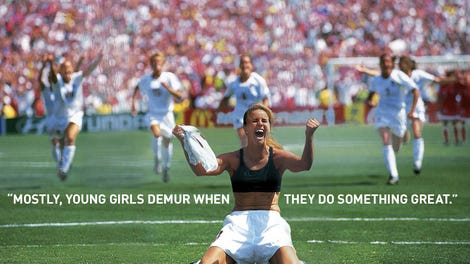

Photographs of the masked terrorist were part of the exhaustive, breaking-news coverage. But it soon became the defining image from Munich, juxtaposed against Spitz’s golden-boy poster and Korbut’s pixie-ish charms.

Russ McPhedran’s photo first appeared in the Sydney Morning Herald. His image is nearly identical to the Associated Press photo taken by Kurt Strumpf. They might’ve literally been standing next to each other.

But because of the AP’s breadth, Strumpf’s version has received the most acclaim. It was selected as one of the 100 most influential photographs of all time for a book published by Time in 2015. “The violence emerges unexpectedly and faceless out of the predictable order,” Strumpf was quoted in the book.

The photo came on the heels of the many explicitly violent images from the Vietnam War, including Eddie Adams’s “Saigon Execution” in 1968 and Nick Ut’s “Napalm Girl” in June of 1972. (Both Adams and Ut were AP photographers whose work was championed by Horst Faas, who was supervising Strumpf at the Munich Olympics.)

And yet, it’s the masked figure’s implicit threat of violence that is its most compelling feature. “I think the reason it’s so haunting is that no one had ever seen anything like that before,” McPhedran said. “It was the first big terrorist attack in the public eye, and it was at the Olympics. To get a guy like this — what an impact.”

“You ask if the photo would be as famous if we could see the face of the terrorist,” Jim Webster said. “Quite simply, no.”

When Russ returned to Sydney after Munich, he’d been away for so long and so much had changed. “When I walked into the kitchen,” he said, “my wife and I didn’t know what to say to each other. It was like meeting a stranger after four and a half months away.”

His work in Munich boosted his reputation at Fairfax. He went on to shoot eight consecutive Olympics in his career, concluding, appropriately enough, with the 2000 Sydney games.

By then, he’d left Fairfax; Horst Faas hired him to lead the Associated Press’s photo bureau in Australia. McPhedran spent nearly 20 years with the AP, until he retired in 2004.

He and Shirley still live in Sydney. He recently suffered a health scare and was hospitalized for a spell. He remains proud of an iconic image that he and other photographers captured, and says he feels “no jealousy whatsoever” over the publicity that Strumpf has received, allowing that the latter’s photo “was better quality.”

As the masked man of Munich turned into the poster boy for terrorism, it became apparent that 1972 would not escape the disquieting shadow of 1936, only echo it. The two Olympics share another thing in common: they have generated more articles, books and movies than all of the other Olympics combined.

The Blood of Israel, written by the late Serge Groussard, remains a go-to resource about Munich because of its detailed reporting. Other books include Simon Reeve’s taut, exhaustively researched One Day in September; Aaron Klein’s Striking Back: The 1972 Munich Olympics Massacre and Israel’s Deadly Response; David Clay Large’s Munich 1972: Tragedy, Terror, and Triumph at the Olympic Games; and Richard Mandell’s The Olympics of 1972: A Munich Diary.

The first film released about Munich was Visions of Eight, a documentary in which eight distinguished directors (Milos Forman, Claude Lelouch) each produced short, personal films. John Schlesinger’s segment about the marathon was intercut with scenes of the standoff outside 31 Connollystrasse.

Schlesinger happened to film the masked terrorist at the precise moment when McPhedran and Strumpf were taking their photos. The footage is in color and lasts for about 20 seconds. The terrorist is shown wearing a bandana beneath his ski mask to shield the lower part of his face. It’s unclear whether he is holding a machine gun.

A forgettable 1976 made-for-TV movie about the incident, 21 Hours at Munich, incorporated footage from Visions of Eight, as did One Day in September, Kevin Macdonald’s Academy Award-winning documentary from 1999. The latter focused on the failings of the organizers’ security preparations as well as the Germans’ disastrous response to the attack.

There have been many other films about the 1972 Olympics, produced by ABC, NBC, and filmmaker Bud Greenspan for Showtime, as well as films produced in Germany, England and Israel. Steven Spielberg’s Munich (2005) was a dramatic account of Operation Wrath of God, the Israeli government’s attempts to kill the surviving terrorists and the attack’s planners. Most recent is last year’s Munich ’72 and Beyond, a 45-minute film about the fight of the families of the victims to have the IOC memorialize their relatives’ lives. (The IOC finally did so, for the first time, two days before the 2016 Summer Olympics.)

None of the English-language works about Munich identifies the masked terrorist by name. None of the journalists, historians, or photographers that I spoke with, including McPhedran and Webster, can recall seeing a caption that identified him. (Presumably, the memoirs written by two masterminds of the attack have identified this man, but those books have not been translated into English.)

The best clues about his identity come from One Day in September — both the book and the movie. Both showed gruesome postmortem images of the hostages and terrorists. (The photos were so upsetting that producers honored requests of the hostages’ families to blur sequences showing their relatives’ dead bodies.)

One of the terrorists is shown lying on the ground, dead, with a machine gun next to his body. He is wearing a yellow turtleneck sweater identical to the one worn by the masked man on the balcony. His head is no longer covered by a ski mask; he has long hair that would have fit right in at any European discotheque in the ‘70s. It’s apparent that he has been shot several times in the face.

(Graphic photos can be seen here and here.)

If the man on the balcony and the dead terrorist at the airbase are one and the same, as seems likely from these images, then it’s finally possible to identify him. He is Khalid Jawad, also known as “Salah,” described in Reeve’s book as “a soccer-loving youngster who lived in Germany for two years before the Black September assault on the Israeli team.”

To this day, his masked face hovers over Munich like a vulture.

David Davis is the author of Waterman: The Life and Times of Duke Kahanamoku.