Two weeks ago Jim Paglia, a 63-year-old businessman, was moving home. The boxes in his new house no doubt contained possessions of personal interest. But hidden amongst the stacks was also a collection of documents that would intrigue the soccer public too. The boxes contained perhaps the last remnants of a failed bid against MLS’s claim to America’s first-division status: proposals for a single-entity league that looked to radically Americanize soccer and attract fans to a sport that had been in hiatus professionally for nearly a decade. This, the plans show, would have also meant changing the game. There would be electronic sensors, pitch divisions and Lycra-like jerseys. Goals? They would be replaced by points. And the goals themselves? Well, there would be four of them.

“Soccer is one of the most popular sports in the world to play – and it is one of the most popular games in America to play,” Paglia, who named the competition League 1 America, tells the Guardian. “But it isn’t one of the most popular games in America to watch. Almost anywhere, you could insert the elements that we developed with League 1 America and draw more spectators. And that was the real purpose: to put a product on the field that would draw more fans.”

The beginning

Paglia found out about the opportunity to start a new league while working on the push to bring the 1994 World Cup to Chicago. Having helped move the United States Soccer Federation to the city years earlier, Paglia, who was chairman of the World Cup Chicago ‘94 organizing committee, successfully helped secure the opening ceremony – and game – for Chicago.

As part of the stipulations for the United States being granted the World Cup, Fifa had stated that the country needed to start a new Division 1 league – something America had been without since the North American Soccer League went bust in 1984. During the NASL’s heyday, Paglia had worked as a self-confessed jack-of-all-trades for the Rochester Lancers. While at the Lancers, Paglia played soccer, learned how to coach, and attended meetings on behalf of the team’s owner, John Petrossi.

Having seen the Lancers, and later the NASL, fail, Paglia felt that he had a good grasp of how to make soccer more appealing to the US public. The stadiums, he decided, needed to have some form of entertainment complex attached to them; the game itself needed to be made more suited to the American viewer, too. This entertainment aspect would form the spine of League 1 America’s strategy. Their bid would be pitted against those from the American Professional Soccer League – the de facto top tier league at the time, but without Division 1 status from Fifa and the USSF because its teams crossed borders into Canada – and the fresh start of Major League Professional Soccer, a precursor to MLS.

Whichever proposal the USSF board approved, Fifa would then have to grant its Division 1 status. The hope was that this league would be in place by 1995, building off the fervor of the World Cup.

The plan

Between 1991 and the summer of 1993, Paglia worked on proposals for a that would see a parent company, Entertainment and Destination Enterprises Inc (EDE), essentially create, develop and run the league. Players, marketing rights, the stadia, their surrounding complexes – all would come under the EDE umbrella.

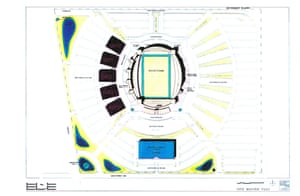

EDE intended to develop 12 complexes across the country, with each 60-or-more-acre plot including a soccer stadium. These complexes would be at key focal points in the metropolitan areas, and include 20,000-plus seat stadiums that were all practically the same: 100 skyboxes, state-of-the-art broadcast facilities, video scoreboards, the capability to host non-soccer events, identical layouts and appearance.

For players, EDE documents state that they intended for League 1 America to be a “made in America product”. Having seen the NASL fail due to its overpaying of aging foreign stars (among other things), EDE decided that League 1 America teams should be limited to two players from outside of North America.

These proposals – if EDE could find investment – sounded promising. League 1 America proposed a competition in which entertainment came first and aimed to prevent repeats of the boom-or-bust leagues of the past. But despite this framework, the entertainment-at-all-costs approach meant that included in the plans was a crucial line: “innovative rules and regulations designed to bring more excitement to the game.”

Changing the game

Really, “innovative rules” meant really innovative. Same skills, same basic components … but a new game.

When putting together plans for his league, Paglia was approached in early 1993 by a doctor called Jay Kessler. Kessler, Paglia said, had been working on proposals for a new version of soccer that he thought would be more suited to the US sports fan. Although he had coached, played and been involved with soccer most of his professional life, Paglia admitted that he did not find the game that interesting to watch, and agreed to hear out Kessler.

“I loved it,” Paglia said. “I thought it was magnificent – and I still do. I still believe it has a place somewhere in the world.”

Over the months that followed, it was agreed that EDE would use the altered version of the game, named ProZone Soccer, for their league.

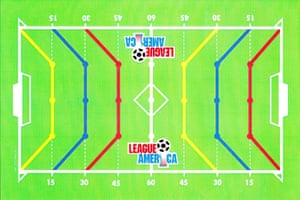

The game being proposed saw the pitch divided coloured chevrons, limiting certain players’ movements within these zones. Players would also wear different coloured shirts based on their positions to help distinguish the zones they were allowed to enter – red for defenders, blue for midfielders, yellow for forwards, white for strikers. (Defenders, diagrams showed, could only go 45 yards from the opposition’s goal but 15 yards from their own goal, for example.) In order to monitor whether a player had entered an unpermitted zone, eight officials would be present, and each player would wear an electronic signalling device that would set off a series of buzzers and lights in the high tech stadiums.

There would also be a points based system, so long-range goals would be worth more. These points ranged from one for a striker to three for a defender, and a team could earn an extra half point if their player scored between the posts of the traditional-sized goal and a new, larger outer goal that was being proposed.

This outer goal, the plans hoped, would make games more difficult for modern day goalkeepers. “When goalposts were first designed, the average English goalkeeper was 5ft 7in,” Paglia explains, “whereas today the average keeper is over 6ft tall.”

Instead of halves, games would be split into three 20-minute periods. Each team had to change some part of lineup between the first and second period; in the third period they could use a the first period’s lineup, the second period’s lineup, or a completely new line-up altogether.

Having seen American professional soccer stumble before, Paglia believed this revolutionized version of the game would help combat three of the failings of the past. First, he felt that soccer needed to be made simpler for new fans to understand. He also hoped that the game could appeal to those who perhaps did not like the conventional version of the sport. In a series of experiments, in early 1993, around 200 US fans who had declared that they did not like watching soccer were asked to attend a version of the ProZone game.

Going into the experiments, the fans were not told the rules of the game. When they felt that they understood the rules, they were to look at the clock and write down the time, what they thought the basic principles were, and whether they liked what they saw. Paglia said that between 90-95% of fans understood the game within the first 12 minutes “because it was so sensual and auditory”. This, he hoped, would allow those who had never liked or watched the sport to quickly become intrigued.

Secondly, for those who perhaps played the sport but did not like to it as a spectacle, ProZone offered an alternative. Paglia likened it to softball and baseball: many Americans play softball growing up, but in terms of which they prefer to watch, people would prefer to flock to baseball.

“The conventional version is the one that you can play,” Paglia says. “My version is the one that you can watch.”

The final problem Paglia hoped ProZone would address was the feeling that soccer was not in keeping with how Americans watch sport. He thought that indoor sports in America – like basketball and hockey – may be fast-paced like soccer, but contain high scoring, small sides, or a star player that people come to focus on. With outdoor sports, though, Paglia believed American fans prefer to discuss the tactical element behind things; they put themselves in the position of the coach.

“To be a spectator in an American sporting event, you have to be able to sit next to someone and speculate,” Paglia says. “‘Oh, I think he’s going to throw a pass.’ ‘Oh, I think they are going to blitz.’ ‘Oh, I think the pitcher is going to throw him a curveball.’ If you’re watching a regular soccer game and you’re talking to the person next to you, you’re not really watching the game.”

Involving a constant flow over two 45-minute periods, soccer does not allow easily for speculation, as focus needs to be on the game at all times, Paglia said. ProZone slowed things down. It hoped to allow fans to speculate whether, for example, a player should have gone for an extra half point between the posts, or passed to a player further out to score more points. It also hoped that the tactical changes that needed to be made between periods would increase speculation, making viewers put themselves in the position the coach, the overall team – not an individual player.

The voting

Confident in the findings, ProZone Soccer’s version of the game remained in League 1 America’s proposals until decision time. The press did not know. EDE had also not signed a formal agreement with Kessler (the parties wanted to wait until the USSF decision was made).

Paglia’s work began to pick up attention in the summer of 1993. Whether fans would later decide that the ProZone was a bastardization or an improvement on conventional soccer, League 1 America’s proposals did grab the attention of Fifa, who invited Paglia to their headquarters in Switzerland to discuss his vision, in September 1993. On his return, Paglia, who had been told by Fifa officials not to discuss the meeting, was greeted by calls from reporters who had been tipped off (some reports since have suggested that this was an attempt by Fifa to hurry the USSF into making decision.)

The USSF intended to make their choice of league in December 1993. According to Paglia, by time EDE were ready to make their presentation, League 1 America had options on land in eight cities (Chicago, Orlando, St Louis, Boston, New York, Atlanta, Dallas, and Washington DC), two in negotiations (Los Angeles and San Diego), and two that were undecided. The group were “pretty far along” with the 12 corporate sponsors, and had all their financing in place, he added.

Though EDE had perhaps been more aggressive in their off-field planning than their rivals, League 1 America was up against a bids that offered one fundamental difference: conventional soccer.

The APSL bid had been in the works since 1991. MLS’s proposals were similar in some ways to those of League 1 America. They, too, proposed a single-entity league; intended to introduce rules – such as shootouts – that would make the game more interesting (though nowhere near as radical as League 1 America’s); and decided to focus on domestic player development. Although new stadiums were preferred, MLS did not make them their first priority. This meant that the league essentially found a middle ground between League 1 America’s innovation and the APSL’s existing lower-level teams. MLS was conventional soccer with a fresh start: something the USSF had been looking for from the outset. The MLS bid also had the support of Alan Rothenberg, the USSF president at the time.

By the time he entered a Chicago hotel to give his presentation, Paglia said that any confidence he had in League 1 America being selected had been shot. “I kind of knew when I went into the room that we were going to lose, but at that point I had to go through with it,” he says.

Paglia’s hunch may have been caused by thoughts that Fifa would dislike a league that did not play the conventional game; that MLS was seen by its rivals as the USSF’s preferred choice all along; or because earlier discussions Paglia later claimed he had with key USSF members had ended on a sour note. Either way, his senses ahead of the presentation were correct. MLS was the chosen as America’s Division 1 league, with 18 votes to APSL’s five. League 1 America did not receive a single vote.

“I remember the Paglia presentation well,” Dr Bob Contiguglia, the only voting member who is still on the board today, tells the Guardian. “He was looking at downtown locations for stadia which would be attached to amusement parks and shopping malls. That was novel but unacceptable at the time. It was more like a circus and I did not take it too seriously.”

Contiguglia adds that the board’s decision has proven to be a wise one: “MLS had the most thought-out and professional presentation, could prove that they could fund a league and comply with Federation Division I Standards. They intended to work with the federations, had strong owners and potential for sustainability, which has since been proven. Not only was the Paglia concept odd, we also did not think it was financially sustainable.”

On 17 December 1993, the USSF presented its business plan for a Division 1 league to the Fifa Executive Committee. And by the time the World Cup kicked off seven months later, with a match Paglia had helped bring to Chicago, seven of MLS 12 franchises were already in place. In the months that followed the decision, League 1 America continued its push for legitimacy, but to no avail. Without the Federation’s approval for the likes of player signings, League 1 America and its modified version of the game had no hope. Paglia stopped working on league in 1995, claiming that he still received expressions of genuine interest up until that time.

“I can’t imagine League One America would’ve worked,” says Beau Dure, a Guardian contributor and the author of Long Range Goals: The Success Story of Major League Soccer. “National team players, from the USA and elsewhere, surely would’ve steered clear for their own developmental sakes. Today, we know we have a strong soccer fan base, and MLS is out to win over that group, not curiosity seekers.”

Today

Since the failure of his bid, Paglia has shied away from interviews about the topic. He never brings up League 1 America in conversation, and admits that not many Americans, soccer fans or otherwise, know about the other Division 1 bid that was made to challenge MLS.

Paglia still loves the game, watches matches and works with soccer-based clients on a regular basis. But unless he has a vested interest in a player or team, he, just like 20 years ago, continues to find the sport boring to watch. Paglia can’t help but think that there are still some elements of ProZone Soccer that could benefit the game today. “I still think it’s a more entertaining version of the game for those who don’t have a dog in the fight,” he said. Occasionally, Paglia will get contacted about reviving the ProZone effort, but having moved on from that project within a year of the USSF’s decision, that has never really been an option.

Before his recent move, Paglia worked as an assistant coach for an Indiana girls’ high school soccer team in his spare time. He hopes to find a new team to develop once the boxes at his new home are unpacked. Once, there had been multiple copies of his vision, handed out to the USSF Board in the hope of starting an exciting, new league which, along with mega entertainment complexes, intended to stamp “America” on soccer. Today, Paglia’s dream remains only in a collection of charts, stadium designs, logos – as well as a diagram of a chevroned pitch that, to a soccer fan, might not look even look like soccer at all.

“Slowly but surely, I’ve trimmed the pile,” Paglia said. “The next time my kids come to visit, I will hold a small bonfire to close the book on EDE and League 1 America.”