What real threat does Zika pose to the Rio Olympics? History has an answer – CNN

Sixteen years ago 90 people came down with meningitis in nine European countries and 14 people died. Epidemiologists tracked the outbreak to pilgrims returning from the Hajj. This annual trek of more than 2 million Muslims to Mecca has in recent years attracted concerns over its potential to distribute the MERS virus in a similar fashion.

The 2012 London Olympics went off without a hitch, though, thanks to the most comprehensive surveillance and triage system for a large event the world has ever seen. The games have made a lasting impact on the public health infrastructure in the United Kingdom, which now benefits from real-time data about syndromes: the collections of symptoms patients complain about. Detecting patterns in early symptoms is critical to recognizing new emerging threats quickly, permitting public health authorities to devote appropriate resources to stop their spread.

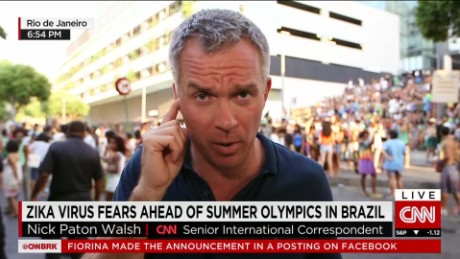

What does this mean for the Rio Olympics?

While Rio 2016’s health and safety infrastructure will surely learn from London’s experience, the Zika virus poses a particular challenge in that 80% of cases have no symptoms, and thus won’t get detected in a syndrome surveillance system.

The mosquito population primarily spreading the virus reaches its lowest numbers during the Brazilian cool season, which includes August and September when the Olympics and Paralympics will be held. But the temperature still hovers between 65 degrees F at night and 75 degrees in the day, so the mosquitoes bite year-round in the region. Brazil suffered a chikungunya outbreak of several hundred cases in mid-September 2014. It quickly bloomed into 722 probable cases in 10 cities by the first week of October, and that’s a virus borne by the same mosquitoes.

Freed from their natural environs, we know that up to half of all travelers engage in casual sex, which can also transmit Zika if they don’t use condoms. Travelers can also spread Zika to sexual partners back home, or to native mosquitoes who will transmit it locally. While Brazil will be enjoying its mild winter this August, many travelers to the Rio de Janeiro Olympics will return to Northern Hemisphere countries such as the United States precisely when mosquito populations are peaking.

Brazil is launching a herculean effort to fumigate Rio for mosquitoes, and most of the Olympics events will be held in that one city, but it has a native population of 12.9 million sharing a varied geography that includes rain forest and beaches. The hardy Aedes aegypti mosquitoes that carry Zika can reproduce even within a dab of water lying in an overturned bottle cap.

Brazilian leaders have shown a willingness to get as creative as the mosquitoes, having been among the first regions to deploy genetically modified mosquitoes and exploring other mosquito control options as well.

Should the Olympics be canceled or postponed?

Prominent voices have called on Brazil and the International Olympic Committee to call off this year’s games. New York University bioethicist Art Caplan said Brazil is being irresponsible with public health. The country shouldn’t be “trying to run an Olympics and battle an epidemic at the same time.”

The U.S. Olympic committee apparently told athletes who are concerned about their own health to skip the games if they want to, and soccer star Hope Solo has gone on record saying she won’t go unless the situation changes. We’re also seeing other sporting events, like the PGA’s Latin American tour, postpone upcoming dates.

But so far Rio stands defiant against the naysayers and the mosquitoes. The games’ spokesman told Conde Nast Traveler last week that cancellation “has never been mentioned. No way.”

Some experts in public health and infectious disease are supporting Brazil’s decision. Dr. Mary Wilson of the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, currently working with University of California, San Francisco, said the fact that the games are held in one city, and during the colder months, means officials should be able to reduce the risk of Zika to an acceptable level.

Dr. Daniel Lucey of Georgetown’s O’Neill Institute for National and Global Health Law similarly said that Brazil is up to the task, and that “the world has an opportunity to respond better, stronger, faster to this epidemic” than officials did with Ebola. Eskild Petersen, editor-in-chief of the International Journal of Infectious Diseases, said “Controlling Zika at present is a problem of mosquito control and once the authorities get that working, the risk will be reduced.”

On the other hand, Dr. Kamran Khan, an infectious disease physician and scientist based at St. Michael’s Hospital in Toronto, thinks some people attending the games will become infected with Zika and “inadvertently introduce the virus back to their home countries” because the Northern Hemisphere will be in summertime. “Even one chance event could cause local transmission” back home, he said. Khan’s research specialty involves the risks associated with mass migrations and he is the founder of BlueDot, a privately held company that exploits big data to model and mitigate infectious disease outbreaks.

To reduce the risk of local outbreaks, Khan recommends attendees to the Olympics take extra effort to minimize their exposure to mosquito bites for two weeks after returning home, whether or not they’re experiencing symptoms.

The best hope for Rio 2016 is that sufficient “herd immunity” will have occurred in the native population, due to infections already come and gone by August. Visitors could enjoy some of that protection, too, but it’s too early to predict when the outbreak will peak and herd immunity will be a factor.

Rio health threats beyond Zika

Even if experts and Olympics officials are confident about reducing the risk of Zika spreading during the games, athletes and visitors to Rio already face a host of potential infections. The city’s bay and lagoon are still contaminated with dangerous bacteria due to unprocessed sewage.

In one study, 30% of soil samples from a popular Brazilian beach contained a hookworm parasite that’s carried by most dogs and cats in the region. It commonly plagues visitors by causing an itchy rash that can then serve as an entry point for bacteria.

Doctors specializing in travel medicine often recommend travelers to Brazil take medication to prevent malaria infections, and take a yellow fever vaccination, in addition to making sure routine vaccinations are up to date. Chickungunya and dengue viruses are now both endemic to the area as well, and there’s a new dengue vaccine some visitors may want to consider.

Zika is just the latest of many potential health concerns diligent travelers need to consider when visiting Brazil, a vast country that encompasses the world’s most important rain forest. Accepting some risk may be the price of enjoying its beauty.

Brazil will be open to the world this August and prospective travelers will need to stay alert to the evolving Zika threat, and the Olympics organizers have much work ahead in earning and maintaining the trust of the international community.

Follow CNN Health on Facebook and Twitter.