‘A League of Their Own’ Is an All-Time Great Sports Film – The Ringer (blog)

Growing up in Lompoc, California, a mostly rural town north of Santa Barbara, Kelly Candaele was vaguely aware that his mother, Helen Callaghan, and his aunt Marge had played professional baseball back in the day. His mom still had her old glove, and would sometimes participate in local powder puff games. “You don’t hear that from other mothers,” he says. But it wasn’t until he got to college, and began understanding the broad contours of American history and women’s places within it, that he realized the significance of his mother’s and her teammates’ stories. He interviewed former players, went to the National Archives to find footage, and put together a documentary about the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League, called A League of Their Own, for the Los Angeles public TV station KCET in 1987. The project was soon aired nationally on PBS, where Penny Marshall noticed it.

Growing up in Lompoc, California, a mostly rural town north of Santa Barbara, Kelly Candaele was vaguely aware that his mother, Helen Callaghan, and his aunt Marge had played professional baseball back in the day. His mom still had her old glove, and would sometimes participate in local powder puff games. “You don’t hear that from other mothers,” he says. But it wasn’t until he got to college, and began understanding the broad contours of American history and women’s places within it, that he realized the significance of his mother’s and her teammates’ stories. He interviewed former players, went to the National Archives to find footage, and put together a documentary about the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League, called A League of Their Own, for the Los Angeles public TV station KCET in 1987. The project was soon aired nationally on PBS, where Penny Marshall noticed it.

“As soon as she saw the film, she contacted us and said, ‘Oh, come out to my birthday party,’” Candaele remembers. “So all of a sudden I’m at a birthday party with Bruce Willis and Demi Moore and John Kerry, the senator from Massachusetts, who happened to be there. All of a sudden I’m hanging out by the pool with Robert De Niro and all of Penny’s movie star friends.” Candaele also met Lowell Ganz, “one of those nerdy baseball junkies” and a talented screenwriter who, along with his writing partner Babaloo Mandel, also wrote the comedy hits Parenthood and City Slickers. Known for their snappy writing and funny, flawed characters, Ganz and Mandel’s involvement was a great sign that the adaptation of Candaele’s story would be in the best hands.

This Saturday marks the 25th anniversary of the Hollywood version of A League of Their Own, which first hit theaters on July 1, 1992, and has remained a constant cultural presence ever since. In 2005, the American Film Institute ranked “There’s no crying in baseball!” as one of the top-100 film lines of all time, but if you were to ask 20 different people for their favorite quote from A League of Their Own, you’d be likely to get 20 different lines.

“There’s like two or three things that people yell out of cars from that movie,” says Lori Petty, who played Kit Keller, the younger of two Oregon farmgirls who go from “plucking cows” to swinging bats. “Like, literally yell out of cars. They’ll yell ‘Mule!,’ or they’ll yell, ‘Lay off the high ones!,’ and I’ll have to say, ‘I like the high ones!,’ and they scream their heads off.”

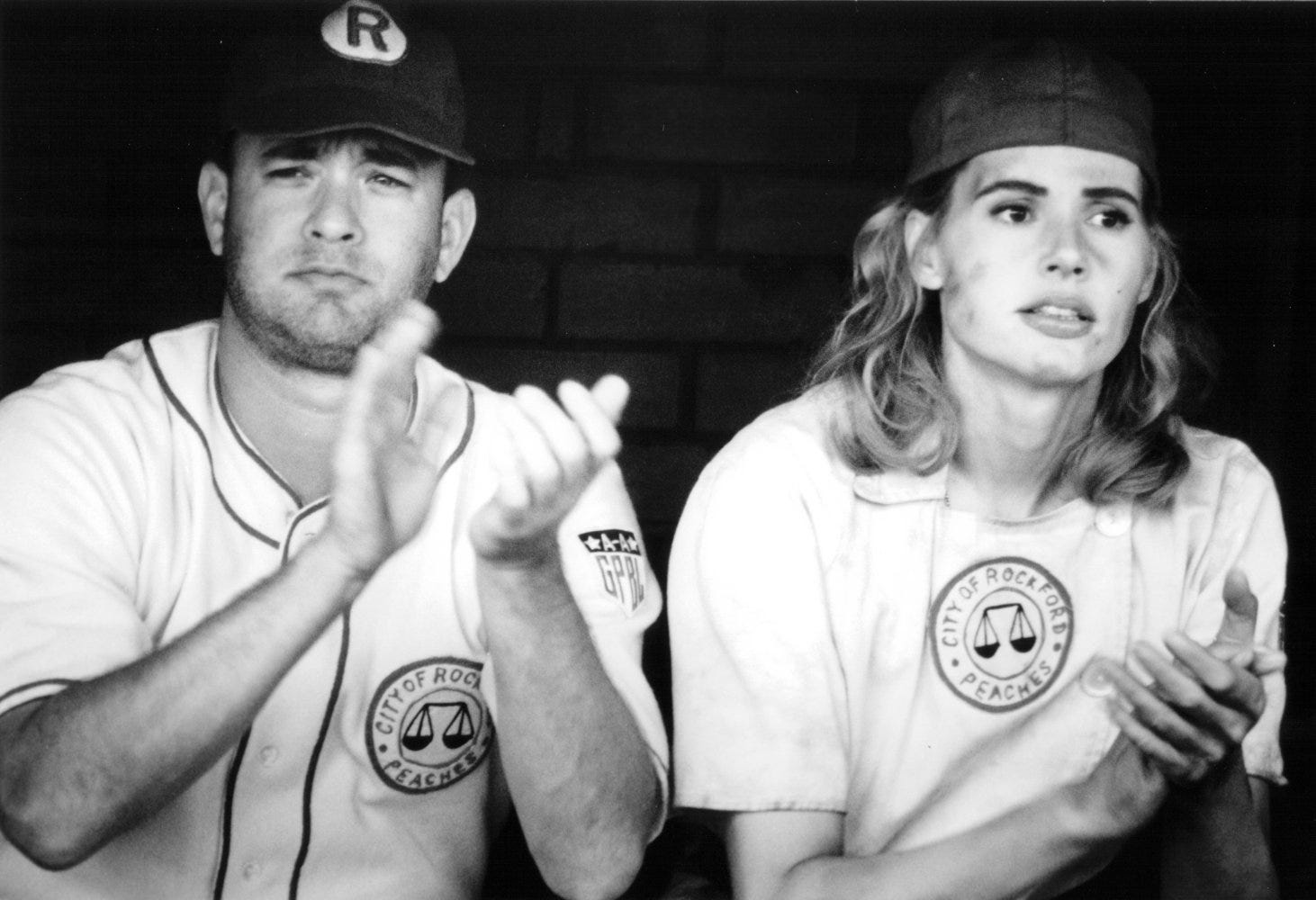

Directed by Marshall, A League of Their Own is a mostly faithful historical tribute to the overlooked women like the Callaghans, who played professional baseball in the wartime 1940s for the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League. Its cast is brilliant, featuring a post–Thelma & Louise Geena Davis, a post–Point Break Lori Petty, and Tom Hanks juuuust before he won back-to-back Oscars. It is, in my possibly blinded by love but also correct opinion, one of the best sports movies there is. And it is an honest ode to women and sisters and friendships, with a story that breezes through the Bechdel test by the end of the opening scene.

“Every woman in Hollywood was reading for this movie,” recalls Petty, who says she auditioned eight times to play Kit, including once at Marshall’s apartment. “It was a strong female movie, which, you know, we don’t have now, and we didn’t have in 1991 either. I mean, Marla Maples auditioned, for Christ’s sake. Everyone.” Téa Leoni and Janet Jones Gretzky earned bit parts as rival Racine Belles. Marshall’s daughter, Tracy Reiner, played the role of Betty Spaghetti. Rosie O’Donnell and Madonna crackled as loyal fast-talking New Yorkers whose best friendship reminded me, for a time, of one of my own. “They became, and I think remain, very close,” says Ellen Lewis, a casting director, referring to the actresses’ IRL bond but also describing the relationship between myself and the film.

It is a frustration of mine, though not a surprise, that A League of Their Own isn’t considered a slam-dunk top-10 all-time sports film. It is the best-earning baseball movie in history, and it holds up as well today as it did in the early ’90s. The script and characters are funny and nuanced, and the mood isn’t dampened by a forced relationship with a wet-blanket character. (Although, to be fair, and with much respect for the troops, Bob Hinson is pretty dull.)

It is a frustration of mine, though not a surprise, that A League of Their Own isn’t considered a slam-dunk top-10 all-time sports film. It is the best-earning baseball movie in history, and it holds up as well today as it did in the early ’90s. The script and characters are funny and nuanced, and the mood isn’t dampened by a forced relationship with a wet-blanket character. (Although, to be fair, and with much respect for the troops, Bob Hinson is pretty dull.)

The baseball scenes are choreographed and performed so well that they rarely take you out of the film. The frying-pan-sized leg wounds are not makeup; the actress who played the superstitious backup catcher, Alice (Renee Coleman), truly did obtain that enormous strawberry while sliding into a base. The humiliating “gracefully and grandly” charm school that the girls must attend is based on the actual baseball players of the ’40s and ’50s being sent to makeup doyenne Helena Rubinstein for etiquette and beauty instruction. Even the “batter up, hear the call” earworm that is sung throughout the movie — in the clubhouse, on the bus, in your mind for the rest of the day — is the real deal.

John Odell, a curator at the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, says that the movie has helped make the museum’s “Diamond Dreams” exhibit, about women in baseball, one of its most popular areas. “Penny Marshall did baseball, and women, and the Baseball Hall of Fame, a great service by creating a great movie,” he says, noting that she attended the 1988 dedication of the Women in Baseball exhibit and was so affected that she made it the setting for both the beginning and end of the film. “It’s perfectly cast, it’s extraordinarily well written, and it’s a terrific family movie.”

It’s also a true ensemble film, with a set of performances, from the public address guy to the young lad who optimistically propositions Dottie Hinson and is credited as “Dollbody Kid,” that together elevate the movie to the realm of a classic. “It was just a magical time,” Petty says of shooting the movie, then interrupts herself. “But not magic, because everyone worked so fucking hard.”

And yet Anne Ramsay, who played Helen in the movie, told Entertainment Weekly that men still feel the need to lower their voices to a whisper when they confess to her that A League of Their Own is their favorite sports film. The “best sports movies” lists that crop up from time to time almost always underrate the 1992 movie in favor of anything involving Kevin Costner (even Tin freakin’ Cup got more love than the Rockford Peaches on a recent USA Today list) or a pair of boxing gloves. When ESPN ranked its top 20 in the genre using a 14-man, one-woman panel, A League of Their Own didn’t even make the cut. (Neither did The Mighty Ducks, which is ludicrous.) Think of it this way: What would you rather sit down and watch right this minute, and next week, and in 20 years’ time: this film, or Million Dollar Baby? No one wants to admit it, but even the supposedly sublime Field of Dreams is secretly kinda a slog. Do not even begin to @ me about any of this.

Considering how deeply familiar A League of Their Own feels at this point, it is jolting to read trivia and hear stories about the Bizarroworld versions of the movie that nearly came to be. Marshall, a fervent sports fan, former Laverne & Shirley actress, and, at the time, rising director with credits like Jumpin’ Jack Flash and Big to her name, was originally too busy working on Awakenings to take on more than a high-level producing role; Hoosiers’ David Anspaugh was slated to direct.

Considering how deeply familiar A League of Their Own feels at this point, it is jolting to read trivia and hear stories about the Bizarroworld versions of the movie that nearly came to be. Marshall, a fervent sports fan, former Laverne & Shirley actress, and, at the time, rising director with credits like Jumpin’ Jack Flash and Big to her name, was originally too busy working on Awakenings to take on more than a high-level producing role; Hoosiers’ David Anspaugh was slated to direct.

The role of Jimmy Dugan “was supposed to be done starring Jim Belushi,” says Jon Lovitz, who played the abrasive, scene-stealing scout Ernie Capadino, a role that was written with him in mind. At one point, the young actress Moira Kelly was meant to play Kit, but Kelly injured herself on the set of The Cutting Edge and couldn’t participate. Much of the casting took place during pilot season, adding a layer of uncertainty and confusion as shows were green-lit and actors were no longer available. (When a Fox sitcom called Last Man Standing starring O’Donnell got picked up, Lewis recalls, Marshall asked her pal Barry Diller, then the Fox studio head, to pull some strings and get the timing adjusted so they wouldn’t have to recast Doris.) Marshall’s brother, Garry, played the moneybags chocolatier Walter Harvey, a role based on gum mogul Philip K. Wrigley, because Christopher Walken was too expensive.

A number of women were considered for the part of Dottie. In Marshall’s 2012 memoir, My Mother Was Nuts, she named a few names. “Anspaugh had wanted Sean Young in the lead,” Marshall wrote. “Demi Moore had been my first choice for Dottie. … She was coordinated — and a strong actress. Perfect.” But after a studio and director change, Moore “was pregnant when the role came around again,” Marshall wrote. “She literally got fucked out of the part.” Debra Winger was cast, then bailed out shortly before shooting began, reportedly when she found out that Madonna would be joining the film. Lewis says that Madonna’s inclusion “really came from a solely creative thought process … she just seemed actually perfect for the part, and she really wanted to do it.” Still, Winger bristled at being part of what she deemed “an Elvis movie,” Marshall wrote in her book.

When Madonna joined the cast, “She was such a big star in 1991 and 1992,” Petty says, “that we were like, what are we even supposed to call her? You can’t call her Madonna! That’s like calling her the Empire State Building!” Marshall felt the same way. “I couldn’t get the word Madonna out,” she wrote. Her solution? To refer to O’Donnell and Madonna in one breath as “Ro and Mo.”

Rewatching A League of Their Own recently, I was struck not only by how realistic the characters felt, but also by the nature of the relationships between them. Yes, there’s plenty of caricature and archetyping going on, from “All-The-Way Mae” and her flying bosoms to the prim chaperone whom she poisons, in an inspiring act of leadership, so that she and the girls can sneak out to booze and dance. But just about every character (aside from that chaperone, perhaps) is written with generosity and nuance. Even would-be tropes, like the homely girl getting a makeover and a whole lotta liquor, ring true: That’s exactly how a well-meaning group of women would descend upon someone like Marla Hooch.

Rewatching A League of Their Own recently, I was struck not only by how realistic the characters felt, but also by the nature of the relationships between them. Yes, there’s plenty of caricature and archetyping going on, from “All-The-Way Mae” and her flying bosoms to the prim chaperone whom she poisons, in an inspiring act of leadership, so that she and the girls can sneak out to booze and dance. But just about every character (aside from that chaperone, perhaps) is written with generosity and nuance. Even would-be tropes, like the homely girl getting a makeover and a whole lotta liquor, ring true: That’s exactly how a well-meaning group of women would descend upon someone like Marla Hooch.

Mae cuts an intimidating outward presence but is a mother hen at heart, brooding in the backseat of the bus, painting Kit’s nails and teaching Shirley Baker (no relation, but the actress, Ann Cusack, is the sister to John and Joan) to read by sounding out the words “milky white breasts.” Her friendship with Doris might be one of the realest instances of female bonding that I’ve seen in pop culture. (Everyone should strive for one friendship where they are the Doris, and one where they are the Mae.) “She was one of the the dancers. I was the bouncer,” Doris crows to some men at the Suds Bucket as she watches her best friend killing it on the dance floor. She is constantly advocating for Mae in this manner: talking her skills up like an agent, pushing her in front of the cameras like a publicist, being visibly proud just to be in her orbit, but deserving her spot there as well.

My best friend forever when I was a tween had a cool mom who looked like Rene Russo, a subscription to Seventeen, a multidisc CD changer in her bedroom, and what had to have been a lifetime supply of Sunflowers perfume. Needless to say, I spent every second I possibly could in that household. We stole each other’s clothes back and forth and took babysitting jobs as a duo. And one of our favorite things to do was hang out in her room blasting Now and Forever by Carole King. It was the first song on the soundtrack to A League of Their Own, a movie we’d seen so many times that we not only knew all the lines, we could parrot the precise cadences of each one. We played it on repeat until, and well after, her younger brother begged us to please stop.

That A League of Their Own causes me to daydream about my own life at age 11 — that a woman can see her own life reflected onscreen — is the sort of thing that motivates Geena Davis, who has made it her life’s mission to advocate for more voices and representation of women and people of color in the entertainment industry. In 2004 she founded the Geena Davis Institute on Gender in Media, whose mission is to research trends and provide education and outreach aimed at narrowing the gap between what we live in the world and what we see on the screen. And in 2015, Davis started the Bentonville Film Festival, in Arkansas, with many of the same goals: to promote and support films that feature true-to-life diversity in some way.

That A League of Their Own causes me to daydream about my own life at age 11 — that a woman can see her own life reflected onscreen — is the sort of thing that motivates Geena Davis, who has made it her life’s mission to advocate for more voices and representation of women and people of color in the entertainment industry. In 2004 she founded the Geena Davis Institute on Gender in Media, whose mission is to research trends and provide education and outreach aimed at narrowing the gap between what we live in the world and what we see on the screen. And in 2015, Davis started the Bentonville Film Festival, in Arkansas, with many of the same goals: to promote and support films that feature true-to-life diversity in some way.

Since its opening in 2015, the Bentonville Film Festival has incorporated A League of Their Own reunions into its schedule of events: once in the first year of the festival, and again this year in honor of the movie’s 25th anniversary. “[Davis] is a tireless speaker around the world,” says Wendy Guerrero, the cofounder and president of programming for the Bentonville Film Festival. “She’s committed to this on a daily basis. It’s really exciting to see that she’s completely [using] her creativity and her advocacy to say, hey, this is something that’s important to me, having children grow up in a world that reflects the diversity.” A League of Their Own is set during an era when Major League Baseball — and much of America — was still segregated, and save for one brief moment when a black woman serenely throws an errant ball back to Dottie with obvious and devastating skill, there is not much in the way of racial diversity. But the film was a rare female-driven picture that featured strong women and sensitive women and earnest women and jealous women — in other words, that featured people with whom a viewer could relate.

While two of the movie’s most memorable performances came from Hanks and Lovitz, as the Rockford Peaches manager Jimmy Dugan and the snide Capadino, their influence remains carefully limited. Dugan may be a chauvinist marathon ball-scratcher who spits, “I don’t have ballplayers, I’ve got girls,” and tells children to avoid the clap — “that’s good advice!” — but he’s also frequently brought down to size by his unimpressed team, and by the end of the film he even manages to mostly restrain himself when the tearful Evelyn screws up yet again. An early version of the film included a smooch between him and Dottie, but it was scrapped because no one cared to see Dottie slumming it with an impressively bladdered has-been lush while her husband serves in the war. Most sports movies featuring men include some love interest to fill the token female role; A League of Their Own doesn’t operate with this constraint.

Lovitz is in the movie for only a few minutes, but he has zero lines that aren’t instant classics. (“How it works is, the train moves, not the station” is my personal favorite.) His “pickle-tickle” line was ad-libbed. A mooing cow interrupted him so many times that finally Marshall told him to just tell the cow to shut up. She also cut a monologue that involved Lovitz, Babe Ruth, and a hot dog described as a “meat rocket.” When Lovitz protested to her that the inclusion of the scene would surely have garnered him an award nomination, her response was: “You’re in the film just enough.”

The ladies on the set delighted in the reversal of ratios, teasing Lovitz by telling him about how their cycles were beginning to sync. “They’re telling me, ‘We’re all irritable,’” he says, “and they’re like, ‘Jon, don’t you know that when you get a bunch of women together, over time they start menstruating together? And I’m like, ‘Why the hell would I know that?!’”

In 2014, a noted sports movie enthusiast by the name of Bill Simmons wrote a guide with a few pointers for determining what counts as part of the genre. One of them is particularly relevant to A League of Their Own: “Do you inadvertently watch it every time it’s on just because you’re waiting for a specific sports scene (or sequence?)”

In 2014, a noted sports movie enthusiast by the name of Bill Simmons wrote a guide with a few pointers for determining what counts as part of the genre. One of them is particularly relevant to A League of Their Own: “Do you inadvertently watch it every time it’s on just because you’re waiting for a specific sports scene (or sequence?)”

Many of art’s finest works revolve around lasting ambiguity: Did someone kill Tony Soprano? Is this an old lady or a young lass? Are Beatles songs really just hidden vehicles for Satanic creeds? Did Dottie Hinson purposely drop the ball as Kit jump-slid into home plate during Game 7 of the Women’s World Series so her kid sister could finally have the glory?

“I knew you were going to ask me that,” says Petty, because it’s what everyone always wants to know; the internet is filled with painstaking did-she-or-didn’t-she analyses that delve into Dottie’s mind-set; her level of fitness and rustiness following her decision to bail on the team with Dull Bob at the start of the playoffs, only to have a change of heart in Yellowstone; her “high fastballs: she can’t hit ’em, she can’t lay off ’em” advice to the pitcher, who needs only one more out for the championship; her ball protection (or lack thereof); and her maybe-foreshadowing comments at the start of the film to her grandsons (“Now remember, no matter what you brother does, he’s littler than you are. Give him a chance to shoot,” she says to the older one; to the younger, she hisses: “Kill him!”). “They’re insane,” Petty says of the forensic sleuths who talk endlessly about all of this. “I kicked her ass!”

Candaele, when asked if his mother and aunt were like Dottie and Kit, explains that they played outfield and infield, not pitcher and catcher, and “to some extent” had a sibling rivalry, but that “my mom would never have dropped the ball, ever. I always tell people that. People say, oh, she did it on purpose, isn’t that nice and sweet, she let her sister win. No one would do that! The betrayal of your own teammates, not to mention the betrayal of your own integrity … you ask yourself, would I betray my teammates like that, in a World Series game, so my bratty sister could win? I mean, it makes no sense. It absolutely makes no sense. Psychologically it makes no sense. Morally it makes no sense. It’s condescending. If you knock someone over and knock the ball out, that’s baseball.”

Still, there are many who will never be convinced either way. And it’s a testament to the movie’s place as not only an excellent sports movie, but an excellent movie in general, that it remains an unanswerable question.

The League of Their Own CD that my friend and I were obsessed with ultimately got scratched to the point of disrepair, just like our own relationship. Our breakup was spiteful and swift, and even now, decades later, the memory of how quickly we shifted from sisters to strangers, as Carole King sang, cuts like a knife. In a way, though, the drama of it was a fitting end to one of the great friendships — one of the great romances, really — of my life.

The League of Their Own CD that my friend and I were obsessed with ultimately got scratched to the point of disrepair, just like our own relationship. Our breakup was spiteful and swift, and even now, decades later, the memory of how quickly we shifted from sisters to strangers, as Carole King sang, cuts like a knife. In a way, though, the drama of it was a fitting end to one of the great friendships — one of the great romances, really — of my life.

Just ask the Rockford Peaches: Not all endings are happy. Dottie and Kit may have concluded their first (and Dottie’s only) professional baseball season on good terms, with a friendly “Mule! Nag!” call-and-response outside the team buses, but one thing I’ll always wonder, more so than I ever do about whether the dropped ball was intentional, is just how often they saw each other in the many decades that followed. The tearful reaction of the two older Kit and Dottie lookalikes suggests that it might not have really been all too often?

Things sag and droop over time (unless, like Ellen Sue, you marry a plastic surgeon) but they heal and soften, too. Marshall’s decision to set the beginning and end of the movie in Cooperstown added historical flair while packing an emotional gut punch. “One of the biggest challenges of the film was casting the older women,” says Lewis. “Some of the people involved in the movie wanted to do old-age makeup and I was really against that — I thought it was a big mistake. Audiences are smart … I really like a truthfulness in the casting.” Her instinct was right; seeing a grandmotherly, all-growns-up version of Marla is a treat, and the adult Stilwell Angel (speaking of treats), who breaks the news that his sweet mom passed away, also breaks hearts when he relays that she “always said it was the best time she ever had in her whole life.”

Many of the women shown playing baseball at Cooperstown’s Doubleday Field as the credits roll and Madonna’s “This Used to Be My Playground” hits are the real-life All-American Girls filmed during one of their own reunions. Candaele’s own mother was in the late stages of breast cancer when A League of Their Own premiered, and would pass away later that year, but she and her son did get to watch the movie together. “She did say she liked it,” he says. “Obviously it was a bittersweet year for me, and I wish she could have been healthy.”

If there’s a better tribute to her life, though, I can’t possibly imagine it. Guerrero, the Bentonville Film Festival cofounder, said that there are girls who weren’t yet born when the movie first came out who nevertheless show up at the reunions and want to see the uniforms and meet the women who played for the Peaches, whether for real or onscreen. In this way, the legacy of women like Helen Callaghan has persisted across nearly a century of generations of women (and men!). Odell, at the Baseball Hall of Fame, says that in 2006, they “recurated” the Women in Baseball exhibit to allow for room to grow in the future.

“You’ve got this high point of the women in the [All-American League], followed by a real fall-off on women being able to play baseball,” Odell says, “which is followed by the rise of Title IX and the Colorado Silver Bullets and Ila Borders, who played minor league baseball for a few years. And then it kind of trails off. So there’s this ebb and flow to the history, and it really makes it feel unfinished.” There’s an optimism in that word, unfinished, and maybe even a challenge: Someone out there is bound to be the one who will keep the game going, the one who will knock the ball out of the park or at least knock over any obstacles blocking home plate. There is always someone on deck, ready to step to the plate.