Last month, given the chance to affirm that college athletes have basic labor rights, the National Labor Review Board punted. It’s rare that a sports metaphor so perfectly crafted for lazy headline writers is so fitting, but punting—the most cowardly, spineless, and responsibility-evading decision routinely made in American sports—perfectly describes the thought process of the NLRB’s decision, a ruling that brought the most energized campus athletic rebellion in decades to a dead stop. The mealy-mouthed reasoning, according to the NLRB decision, was that “asserting jurisdiction would not promote stability in labor relations.”

http://deadspin.com/nlrb-rules-tha…

Like a coach facing 4th and 1 from the 50, there was no mandate on high forcing the NLRB into the easy and wrong decision. They had every chance to go against the status quo; instead, the highest labor authority in the country chose not to use their power. Sports labor economist (and frequent Deadspin contributor) Andy Schwarz put it best on his blog:

They chose to favor an industry over its primary participants, and to deny those participants what most Americans expect as their due – the right to be heard in court, in an administrative hearing, etc. The decision not to hear them at all was a sort of way of saying: Your Rights Don’t Matter the Same as Others. Why? Youth? Socio-economic status? Race? I don’t know, but I still have trouble thinking the NLRB would have refused to even adjudicate a labor dispute brought by group of 45-year old white workers.

The NLRB told college athletes what athletes across the world— across sports, genders, ages, and ability levels—have been told for decades: The work you do is not true labor. You are not entitled to compensation for the time, effort, and pain that fuels the top-level performances that millions of people spend billions of dollars to see. And when it comes time to step into the bargaining arena with your employers, you have no rights and no protections.

It’s no surprise when this attitude emanates from college football’s patriarchs, whether it’s a conservative coach like Dabo Swinney whining about how he would quit if players were paid “because there’s enough entitlement in this world as there is” or a conniving executive like Walter Byers creating the term “student-athlete” to avoid paying a paralyzed football player workman’s compensation. The purveyors of amateurism have been trying their hardest to convince us there is something gross or unclean about paying athletes since the first English amateur leagues in the 19th century. If we don’t see sports labor as labor, it’s because these men have been screaming at us for 150 years that it isn’t.

“I am shocked because you call playing baseball ‘labor.’”

The NLRB’s cowardly ruling continues an infuriating history of people and institutions devoted to the cause of labor throwing athletes under the bus. Throughout American history, those who profess to fight for labor have responded to athletic unionization efforts with ambivalence at best and outright opposition at worst. When the labor issue is also an athletic issue, solidarity has too often been an afterthought.

Jimmy Hoffa, one of the few labor leaders who pushed for and attempted to organize sports unions, put it succinctly in 1966, when he told the Associated Press that professional athletes face the same problems as truck drivers. “Both want job security and compensation for their work,” Hoffa said. That ideal—the belief that athletes deserve dignity and agency in the workplace—has been the heart of every American sports labor movement, from John Ward’s Players’ League in 1890 to Kain Colter’s unionization effort at Northwestern last year.

We can start in 1915, when the Federal League brought its case against the American and National League monopoly to court in Chicago. This court was specifically selected because of its judge, Kenesaw Mountain Landis. Appleton’s Magazine wrote of Judge Landis, who had previously been a corporate attorney, that “Corporations smiled pleasantly at the thought of a corporate lawyer being on the bench. They smile no more,” and claimed he had “brought down [more] corporate wrath” than any other judge. Landis quickly proved to share in the antitrust sentiments espoused by Theodore Roosevelt when he swung a huge stick at Standard Oil Company in 1907, fining them over $29,000,000 for colluding with railways to distribute their oil at lower costs.

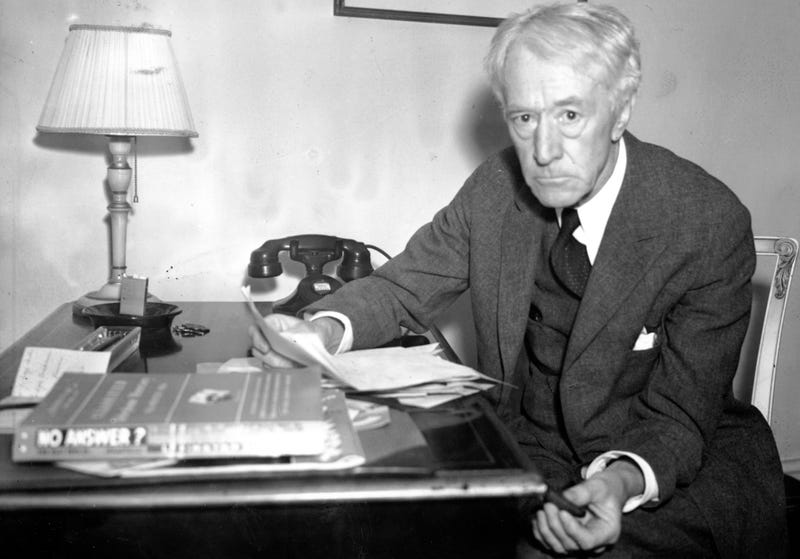

Kenesaw Mountain Landis, 1936. Photo via AP

Landis positioned himself as a champion of the common man. “It is the duty of the Court to carry out the will of the people as expressed in their laws,” he told Appleton’s. J.G. Taylor Spink wrote of the Standard Oil case that it “made Landis many enemies among the conservative element in Washington, who called him a radical, a grandstand player, and ‘Chicago’s showboat judge.’” It wasn’t just Standard Oil, either—the government won multiple antitrust victories in Landis’s court against railway executives. Landis occasionally showed his support for the underdog in heavily symbolic rulings. One day after Woodrow Wilson’s White House commuted Landis’s maximum jail sentence of a chicken purveyor convicted for selling diseased stock, Landis allowed six men convicted in his court of stealing sugar off of railroad cars to go free.

“Stealing sugar,” Landis declared, “is no more deserving of a prison sentence than selling diseased cattle.”

It was this sentiment that made the Federal League believe Landis’s court was the place to try their case against the organized baseball behemoth and the reserve clause. When National League attorney George Wharton Pepper made a reference to “labor,” though, Landis revealed his position with all the delicacy of Babe Ruth making a drink order.

“As a result of 30 years of observation,” Landis admonished Pepper, “I am shocked because you call playing baseball ‘labor.’”

From there on, it was clear the Federal League wouldn’t get the ruling it desired from Landis. Their case rested on not only the illegality but the immorality of the reserve clause binding players to their clubs, the same reserve clause that inspired Ward to pen an article for Lippincott’s Magazine titled “Is the Base-Ball Player a Chattel?” in which he laid out in detail the abuses contained within the reserve clause and attacked it with a fiery righteousness:

This, then, is the inception, intent, and meaning of the reserve-rule in its simplicity: its complicity I will presently describe. It inaugurated a species of serfdom which gave one set of men a life-estate in the labor of another, and withheld from the latter any corresponding claim. No attempt has ever been made to defend it on the grounds of abstract right. Its justification, if any, lay only in its expediency.

Landis made no real attempt to defend it. Instead of ruling in the Federal League case, which had the backing of precedent in Hal Chase’s victory against the American League in the New York Supreme Court the previous year, he simply sat on the case and refused to rule, a decision that ensured Federal League cash reserves would run dry and eventually forced a settlement at the end of the 1915 season. Spink wrote that when reporters asked the judge when he would rule on “that baseball business,” Landis “merely looked the other way and said nothing.” That was the end of the Federal League, and until Flood v. Kuhn 65 years later, the last real challenge the reserve clause faced.

As Shayna M. Sigman wrote in the Marquette Sports Law Review in 2005, “The Federal League case created tension between the outcome Landis desired — Organized Baseball must win — and the process Landis employed — rejecting formal distinctions in an activist way, critically examining the economic reality of the situation, and relying on Progressive principles of moral justice.” Faced with this contradiction, Landis made the same choice as the NLRB made with the Northwestern football union: he punted. He pretended to maintain his neutrality through indecision, but he knew full well his course of action would lead to the Federal League’s demise and victory for the powerful, in this case, organized baseball. Landis could only arrive at this position through a total lack of respect for the labor of baseball players, the same invidious attitude he so brazenly showed in court.

“I wasn’t sure we were strong enough”

With the rights of athletes hampered by restrictions like the reserve clause, the idea of a powerful sports union was unthinkable until the 1960s. Even though the Major League Baseball Players Association had existed since 1953, it was a toothless organization in its early days, staffed by men recommended to the players by the owners themselves, like Marvin Miller’s predecessor as executive director, Robert Cannon.

In 1959, boxer Sugar Ray Robinson announced his intentions of creating an all-inclusive athletes union. Robinson told the Associated Press his union would “include athletes from every sport, not just boxing. And it’ll be under a national charter.” He said he had talked with AFL-CIO president George Meany, “and the more I talk to him,” Robinson claimed, “the more interested he gets.”

Sugar Ray and Edna Mae Robinson, 1957. Photo via AP

Robinson’s idea never got off the ground, though; it turned out that Meany was far less enthused than Robinson either knew or cared to share with the press. Meany denied having discussed the union with Robinson; a spokesman for Meany told the press the two had met just once, four years prior. “I said hello and how are you,” Meany said, “and have not spoken with him or any representative of his since that time.”

Meany’s resistance to sports unions would define athletic unionization efforts and their relationship to the mainstream labor movement for decades. In 1966, as Miller was a candidate for election as MLBPA executive director, Meany had stated ballplayers were independent contractors and didn’t need unions, a view he had expressed as early as the late 1950s. In 1974, he maintained that athletes were “unorganizable,” like white collar workers, domestics, and managerial employees, and that labor’s energies were “better devoted to lobbying for the better life than organizing.”

This was all despite Miller’s already wildly successful efforts to organize major league players into a true and powerful union. By 1973, Miller’s MLBPA had won a new basic agreement and pension agreement. They won the right to have salary disputes adjudicated by independent arbitrators, the single biggest factor in baseball’s meteoric rise in salaries in the 1970s as well as the eventual mechanism by which the players won free agency. (As Miller noted in his autobiography, it produced “the most rapid growth of salaries ever experienced in any industry.”) And much of this was made possible by the solidarity the players showed in the strike of 1972. While Miller admitted years later that “the truth is that I wasn’t sure we were strong enough,” the strike vote passed by an overwhelming 663-10 margin, and the players held ranks through the cancellation of 86 games. Within five years, they had won free agency, and within a decade, major leaguers were earning million-dollar salaries.

Meany stubbornly refused to budge from his view of athletes as independent contractors and part of the business rather than laborers. Victor Riesel wrote that he saw these efforts as “fatheaded.” The argument Meany used to deny athletes their spot at the bargaining table is the same argument companies like Uber are using now to hack away at wages and job stability in the so-called “sharing economy.” The presence of a few mega-millionaire players has not made the 1,500-plus young men drafted into the organized baseball labor force on a yearly basis economically independent, and until the players are the ones supplying the stadia and putting on games themselves, it’s ludicrous to consider them anything but employees.

“Money violence”

Without the help of the AFL-CIO, the early sports union efforts were left to fend for themselves. Hoffa and other Teamsters representatives made attempts to integrate football’s players union into the Teamsters and kickstarted an attempt to form another pan-athletic union, but neither panned out; the Teamsters’ “iffy” reputation (as Miller put it) and the anti-union sentiments carried by many football players, like AFL Players Association director Jack Kemp, made solidarity an impossibility. Although this was well before the enormous salaries that define today’s athletic market—average player salaries didn’t begin to top $50,000 in MLB until the late 1970s, and other sports followed similar patterns—sports unions were seen as “white collar,” thanks in large part to attitudes like Meany’s, and couldn’t count on solidarity during their many strikes in the 1970s.

One complicating factor here was probably that athletic unions were far more racially diverse than the typical American union. By 1970, discriminatory barriers were falling across sports. As of that year, 34 percent of NFL players were black, a figure that jumped to 42 percent by 1975. Black players were so prominent in the NBA that over half the league was black by 1967, and many black players believed the NBA was using an unofficial quota system limiting teams to four black players per roster. And baseball, at the time, featured 27 percent minority representation—15 percent blacks and 12 percent Latinos.

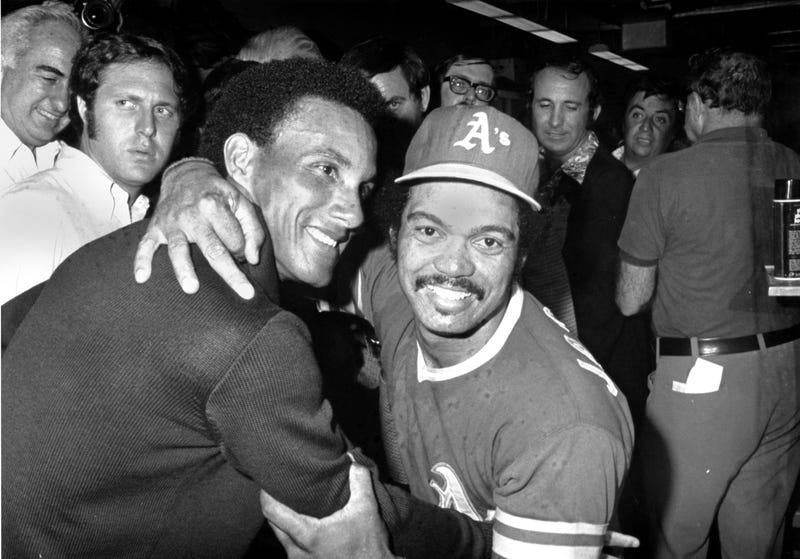

Reggie Jackson and Bert Campaneris, 1973. Photo via AP

Landis’s refusal to stick with his broadly pro-labor principles came from his love for organized baseball. Meany’s history of racism must be considered a factor in his opposition to the sports labor movement. Meany refused to support the March on Washington, accused leaders in the civil rights movement of creating a gap between labor and civil rights, and refused to dispel racist unions from the AFL-CIOs ranks. He demanded the firing of Secretary of Labor George Schultz when he attempted to integrate construction sites in Chicago.

His racism was not uncommon in the labor movement. In his 1984 essay “On Being White… And Other Lies,” James Baldwin wrote, “There has never been a labor movement in this country, the proof being the absence of a Black presence in the so-called father-to-sons unions. There are, perhaps, some niggers in the window; but Blacks have no power in the labor unions.” It is impossible not to see this racial distinction in the fight for sports labor rights. Sportswriters’ fears of free agency in the 1970s and 1980s involved, among other things, a blatant fear of money shifting from the old white establishment to young men of color suddenly in economic control of their own lives. Nowhere was this more obvious than in an editorial from sportswriter Jerry Green, a pro football Hall of Famer, in Petersen’s 1979 baseball preview magazine, in which he quotes an arrogant, newly rich Reggie Jackson (“I’m a black man with an IQ of 160 making $700,000 a year and they treat me like dirt”) to support a hypothesis that the “money violence” in baseball won’t end until “Only the Arabs and Japanese will be able to afford to own a major league baseball franchise.”

Dive into the objections to paying college athletes in cash and you will see expressions of the same fear. Paternalistic concerns over where these athletes will spend their money have loomed whenever the concept of paying college players props up. There is perhaps no better example than the argument the self-appointed father of black America himself, Jason Whitlock, made against paying college athletes in 2002 for ESPN::

I do know only a fool would watch Webber, Jalen Rose and Juwan Howard drive up to practice and games in new SUVs, gaudy jewelry dangling from their necks and expensive leather coats and jackets wrapped around their shoulders and not suspect the Fab Five had a nice source of income.

I do know only a man or woman devoid of his senses couldn’t smell the sense of financial entitlement that wafted from the five teenagers as they made college basketball history and, in their minds, made middle-aged white businessmen wealthy.

Demanding money in exchange for labor is rarely referred to as “financial entitlement.” But Whitlock’s screed belies the true fear of college athlete payment: That these kids will be able to win power and agency; that they’ll be able to express themselves; that they’ll be able to feed and clothes themselves without jumping through hoops; and, worst of all, that they’ll have the power to say no when old men, whether their coaches or lecturers like Whitlock, try to tell them how to live their lives.

Here we are in 2015, and the NLRB has failed to recognize the labor rights of a group of football players, largely black men and men of color, who have dared to suggest the time and effort they put in should be considered work. By suggesting that the stability of college athletic labor relations is more important than the rights of players to organize, the NLRB has implicitly endorsed the current state of affairs, one where players are not only restricted from the billions of profits their work creates, but where some of these players go to bed hungry. All because their work doesn’t count as real labor.

The fight for representation in college athletics wasn’t ended by the NLRB, but it placed an unnecessary barrier across what was already difficult terrain. The sports union fight will always be a difficult one because of the tremendous imbalance of power between the absurdly wealthy bosses and the largely marginalized players. The last thing the sports labor movement needs is foes within labor itself.

Unfortunately, throughout American history, men who otherwise believe in the recognition of and the fight for labor rights have ditched these values when it comes to sports. Instead of seeing the athlete in solidarity, seeing his or her struggle within the larger worker’s fight, so-called champions of labor have instead bought the sports establishment’s vision of the athlete as a commodity, as chattel. From Judge Landis a century ago to the NLRB today, the refusal to see the athlete as a worker has both hindered the fight for labor rights in sports and prevented any solidarity between athletes and the labor movement as a whole. When I look at the remaining fractured and weakened pieces of the labor movement, and a sports industry in which athletes across the board need better representation and protection, I can’t help but wonder what might have been had solidarity not been so selectively applied.

Jack Moore is a freelance sportswriter based in Minneapolis, MN investigating the history and mythologies of sports. His work can be seen regularly at VICE Sports, The Guardian, and The Hardball Times. Top photo via Getty Images