An ode to the Oakland Coliseum, the last two-sport stadium dinosaur … – San Francisco Chronicle

They methodically began to remove padded sections of the outfield wall. Less than two hours later, the wall had vanished from left-center to right-center. So had the pitcher’s mound and both bullpen mounds.

Sit down, baseball. Time for football.

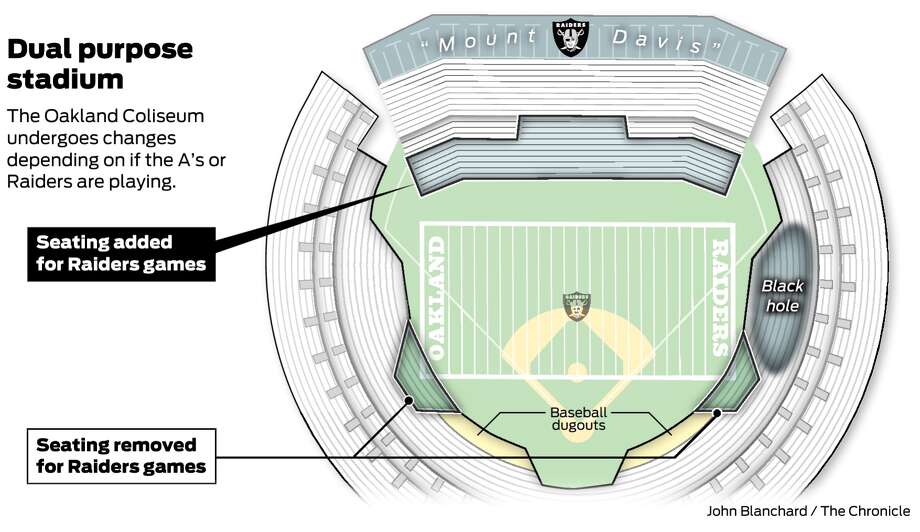

Here in 2017 — a time when stadiums with retractable roofs are common and sparkling sports palaces dot the landscape, coast to coast — the Coliseum counts as a relic. It’s the only full-time, multipurpose professional sports stadium left in the country, an ode to a previous era.

Thirty years ago, no fewer than 12 stadiums were home to both major-league baseball and football teams — including Candlestick Park, which the Giants and 49ers shared from 1971 through ’99. As the stadium construction boom kicked into gear, the two-sport venue came to resemble a 21st century dinosaur.

But the Coliseum plods along in dual and unglamorous service, at least until the Raiders leave in 2019 or ’20 for their new Las Vegas stadium. Oakland’s gray, concrete bowl along Interstate 880 flows with memorable moments on both sides of the ledger — from Catfish Hunter’s perfect game in 1968 to Kenny Stabler’s “Sea of Hands” pass in ’74, from the A’s clinching World Series titles and American League pennants to the Raiders cementing Super Bowl berths.

The teams shared the Coliseum from 1968 through ’81, before the Raiders moved to Los Angeles, then became co-tenants again when then-owner Al Davis brought his franchise back in ’95. Now they remain uneasy partners, the Raiders eyeing their impending departure to Las Vegas and the A’s craving a new, baseball-only ballpark in Oakland.

This two-sport thing is tricky this time of year, with baseball season winding down and football season gaining steam. Soon after the Raiders returned in ’95, then-A’s general manager Sandy Alderson sometimes scoured the outfield grass before his team’s games, scooping up stray nuts, bolts and screws left behind by the crew that had hurriedly removed football bleachers.

Twenty-two years later, the sight of Raiders players rumbling along infield dirt during early-season games remains strangely nostalgic and no less treacherous. On the flip side, A’s outfielders find themselves chasing down fly balls on grass with faded, white football yard-lines still visible from earlier Raiders games.

“I’ve had outfielders going from the 35 to the 40 to the 45 … ” A’s broadcaster Ken Korach said, his voice rising in mock exuberance, “And he’s down at the 49-yard line!”

Watch as the Oakland Coliseum transforms from the A’s baseball field to the Oakland Raiders football field.

Media: San Francisco Chronicle

Last of its kind

Clay Wood, the A’s head groundskeeper, bears the brunt of this multisport challenge. Wood was hired in September 1994, and he moved from Arizona to the Bay Area expecting to maintain a pristine, baseball-only facility.

Then, early in 1995, the Raiders announced their return. Wood’s job suddenly became infinitely more complicated.

Now, after all these years of watching his meticulously manicured field chewed up during the baseball/football overlap in August and September, he’s resigned to the predicament.

“You’re talking about two multibillion-dollar industries in MLB and the NFL,” Wood said. “There’s a reason this is the last multipurpose stadium, and I think everybody understands that. It’s not a good situation for anybody, really.”

Wood joined A’s and Raiders officials for a meeting last year in which they explored ways to sod the infield dirt for football games during baseball season. The Raiders even hired a sports field construction company to propose potential solutions.

But several obstacles got in the way, including limited access to the field and the damage that would be caused by heavy equipment. And so the Raiders played two exhibition games on infield dirt in August, and they will stage their regular-season home opener in the same conditions on Sept. 17.

“Yes, it’s a challenge,” said Tom Blanda, the team’s senior vice president of stadium development and operations. “It’s concerning to the Raiders and anyone who plays football on an infield surface, and it’s also concerning to baseball players.

“It’s an outdated configuration, but we make the best of the situation.”

There and back again

Sights and sounds as the Coliseum is transformed from baseball to football in advance of the Raiders’ preseason game on Aug. 31.

Media: rkroichick@sfchronicle.com / sfchronicle.com

Even if the conversion from baseball to football started moments after the A’s polished off their win over Texas on Aug. 27, it truly swung into gear the next morning, as the sun climbed into the sky above the towering east-side structure known as Mount Davis.

That’s when Bigge Crane and Rigging Co., based in nearby San Leandro, started moving football bleachers from the Coliseum parking lot onto the field. Those temporary seats are stationed along the east sideline for Raiders games.

Just imagine forklifts and modified semitrailers squeezing wide swaths of seats through the center-field tunnel. Every piece of bleachers must be towed down the ramp and through the tunnel, and then cranes painstakingly set those pieces in place.

“It’s extremely cumbersome and labor-intensive,” Wood said.

Retractable bleachers would have been a much more practical arrangement, but mid-1990s budget restraints interfered. So the conversion is akin to a giant jigsaw puzzle, with one crane placing bleachers on the east side and another crane rearranging sections of seats on the west side.

The whole process takes at least 20 hours going from baseball to football, fewer when going the other way. On the most recent transition, there was more time, with three open days between the A’s game on Sunday and Raiders game on Thursday.

This dual existence creates some uncommon sights. Baseball’s foul poles rest at the base of the out-of-town scoreboards during football games, hidden beneath the temporary bleachers. Football’s goalposts are broken into four pieces and stored under Mount Davis during baseball games.

The transformation leaves few details unattended. Green tarps with an Athletics logo are peeled off upper-deck Mount Davis seats, replaced by black tarps with a Raiders logo. In the concourse below, another worker takes down a sign directing A’s fans to the bleachers because, as he said, “God forbid people see anything with ‘A’s’ on it.”

But the biggest, most visible impact of the changeover occurs on the field. As Wood put it, the field can survive 60 baseball games and “go to hell” with one turf-chewing conversion before a Raiders game.

“From April 1 until football starts, life’s pretty good,” Wood said. “But come August, as a groundskeeper in this stadium, life becomes basically survival mode.

“You’re trying to make the field survive and have it playable for two different sports. You’re trying to keep everybody happy and essentially not keeping anybody happy.”

Football players struggle to find reliable footing on dirt while baseball players deal with bumpy, unpredictable grass after Raiders games. The work to move bleachers in and out causes more damage than 300-pound behemoths grappling along the line of scrimmage.

A’s outfielder Mark Canha praised Wood and his seven-man crew for their diligent work under difficult circumstances. Canha acknowledged he typically plays one step deeper during football season, knowing base hits often hop and skid on the uneven surface.

Canha also grew up in the Bay Area, watching Raiders games, so he has fond memories watching his football counterparts play early-season games on infield dirt.

“I don’t think I’d like getting tackled on that stuff, but those guys are tough,” Canha said. “It gives Oakland a little flavor. It suits the Oakland vibe and fan base.”

At least for a couple more years.

Ron Kroichick is a San Francisco Chronicle staff writer. Email: rkroichick@sfchronicle.com Twitter: @ronkroichick

About Us

Free Shipping

If your order is $35 or more, you may qualify for free shipping. With free shipping, your order will be delivered 5-8 business days.