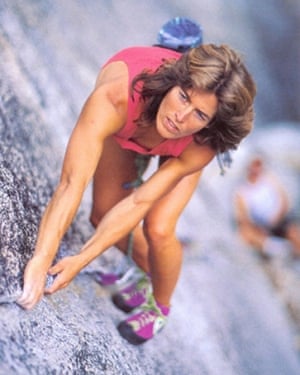

In a 1989 broadcast, David Letterman introduced the greatest climber in the world by saying that the athlete had “a lovely little outfit on”. Lynn Hill had just come off a several-year sweep of climbing competitions, including the world class Rock Master Invitational, and was ranked No1 in the world by the Association of Sport Climbers International. She would go on to complete the first free ascent of the Nose on El Capitan in Yosemite Valley, California, and the first free ascent in under 24 hours, a feat that’s only been repeated by one climber in the 20 years since. She accomplished all this while remaining, as one journalist put it, “probably the greatest athlete the general public has never heard of”.

Women in adventure sports have come a long way since the 80s and 90s, when the majority of outfitters still made gear exclusively for men. But in some ways the same barriers persist. In September, GQ magazine featured a high-fashion climbing spread that was so gendered it seemed almost a farce to many in the climbing community. The glossy article featured three of the world’s best male climbers bouldering in Joshua Tree National Park while ornamented by lightly dressed fashion models who looked on from below.

While the spread prompted widespread scorn (and this sendup featuring “designer clothes for watching ladies climb”), Hill could only laugh at the $3,000 vest in which the magazine dressed one of the climbers.

“Climbing used to be more about non-conformism,” says Hill. “And now with the gyms and the rules and everything, it’s going in the opposite direction, towards conformism.”

With climbing’s popularity booming, it’s subject to mainstream push and pull. But what can feel like progress for the sport might just be more exposure. Despite major competitive accomplishments from female athletes, they still don’t get the kind of attention men do. “The hardest thing to realize is that you can make a lot of effort and there’s still a long road ahead of you,” Hill says.

Acknowledging that gap, the Banff Mountain Film and Book Festival, an annual gathering of the best media makers covering the outdoors and adventure sports, built this year’s theme around women in adventure. The film festival tours all over the world for the better part of a year and strongly influences exposure for adventure athletes.

“Our number one piece of feedback over the last five years is that we want more content that features women,” says Jim Baker, head of the festival’s world tour.

In response, the festival constructed this year’s program to feature notable women in the outdoors, like Hill, who appeared as keynote speaker. From films about athletes like ski mountaineer Kit Deslauriers to books by authors like 2016 National Geographic Adventurer of the Year Sarah Marquis, this year’s offerings feel notably more diverse.

The festival’s grand prize in books went to Ice Diaries by Jean McNeil, a Canadian fiction and travel writer. The haunting memoir draws from a year she spent in the Antarctic, interwoven with stories from dark, cold places all over the world.

The film festival’s grand prize went to Shepherdess of the Glaciers, a feature-length documentary about one of the last female sheepherders in Ladakh, India, who lives alone in the high mountains 5,000 meters above sea level, tending 300 goats.

Hill spoke about her hope that coverage of female adventurers will eventually be broad enough to cement the fact that women are no less capable than men. She points out that while men and women have to climb differently based on different biomechanics, at 5ft 2in, her build hasn’t held her back.

“The modern, ultimate level should be that men and women are – equal is a nice word – but we are unique,” says Hill. “A woman does approach climbing differently from a man. Probably because of a lower center of gravity, they’ll stay over their feet more, while men try to muscle through. But we can have mutual respect in terms of accepting each other.”

The psychological barriers to women competing are as real as anything solid. If women don’t appear as athletes in sports films or coverage in magazine, that has an impact. Hill has advocated for women and men to compete together in climbing events to encourage a movement away from the psychological block against women being competitive.

“The way we perceive challenges has a lot to do with how we manage them,” says Hill. “If you perceive something as being really scary or too difficult – all these little stories we tell ourselves – then it will be that.”

Even for women who don’t want to compete in sports like climbing, the way those pursuits are made accessible and represented still has a broader social impact.

“It’s actually more important for women to do activities that are empowering, like climbing, because social conditioning that happens on a very subconscious level does not tell women that they should be strong and take the lead and be a lot of the qualities that climbing demands of us,” says Hill. “I think it’s very important to challenge ourselves.”

The Banff Mountain Film Festival will tour 41 countries this year. Its UK and Ireland tour runs from January to May 2017 and its US tour runs from December 2016 to May 2017. To find out when the Banff Mountain Film Festival is coming to your town, check out the schedule here.