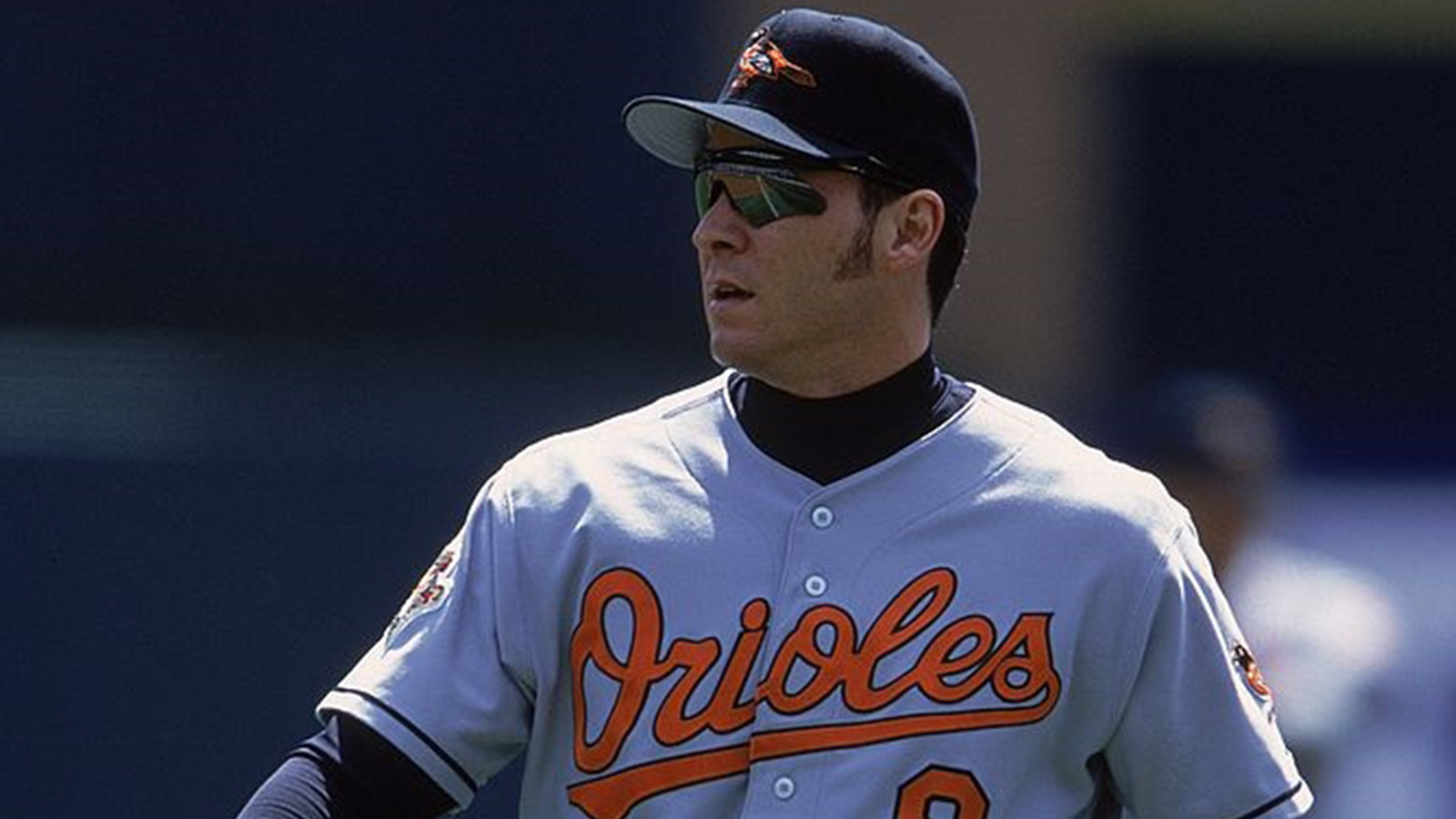

His title is vice president of baseball operations. The Orioles list him No. 2 on their front-office depth chart, just under executive VP Dan Duquette. But to Brady Anderson, a role that typically equates to assistant general manager is not enough.

“I made up my mind early on that I’m not going to stop doing what I’m good at,” Anderson said. “There are things I can learn from somebody like Dan and do better, but I’m not going to stop doing what I can do to help the team.”

Anderson, a former outfielder who played 14 of his 15 seasons with the Orioles, fills a multitude of roles for the club – coaching, overseeing the team’s strength and conditioning program, influencing player moves and occasionally assisting in the negotiating of contracts.

His position is unique within the industry, his duties unusually broad for someone with no previous coaching or front-office experience.

Duquette, manager Buck Showalter and center fielder Adam Jones are among those who praise Anderson as an asset, with Showalter saying, “We view him as nothing but a positive.”

Others with past or present ties to the Orioles, however, consider Anderson a source of friction and tension as he blurs the lines between executive and former player.

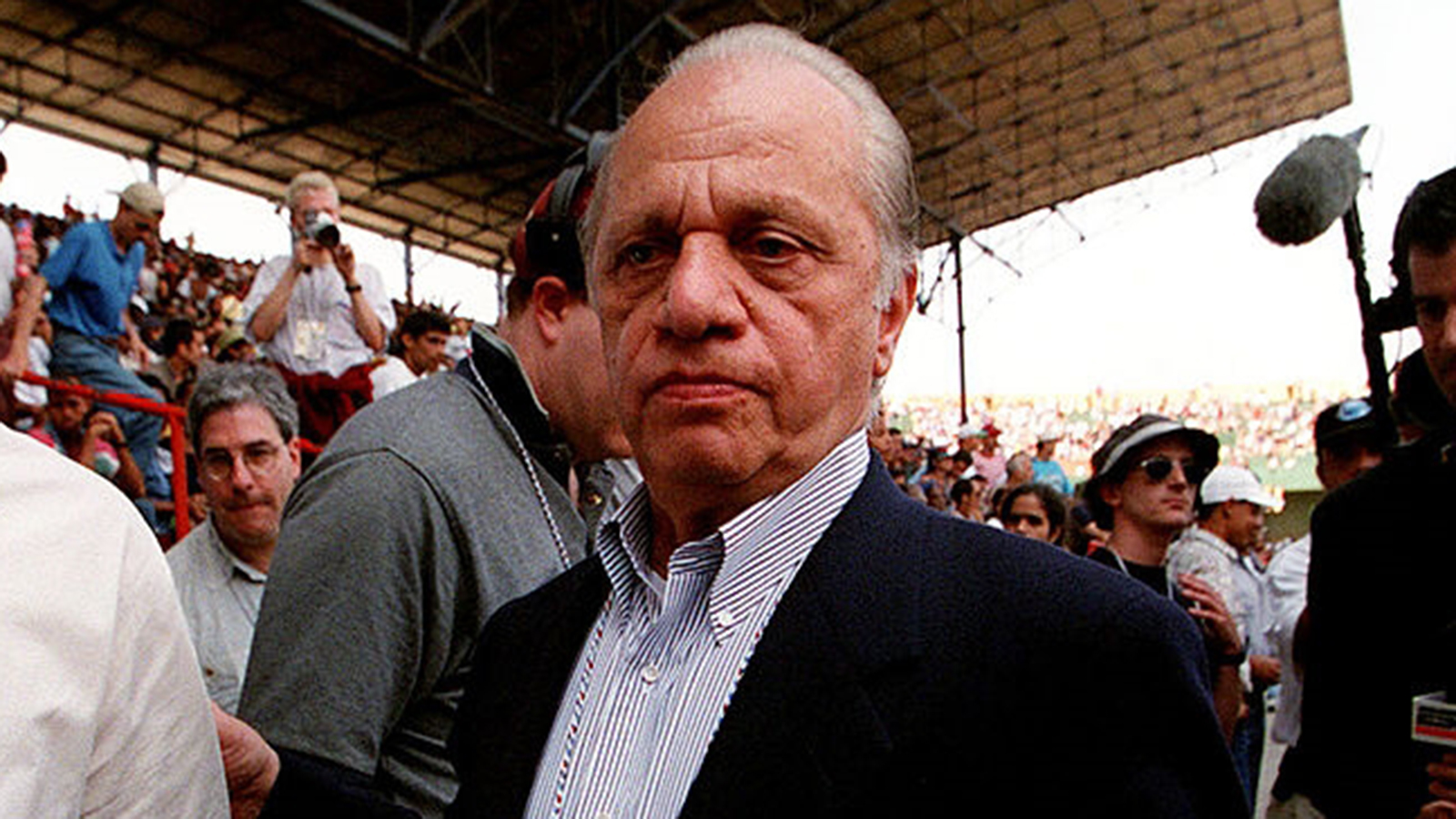

Anderson, 53, is close with both Orioles owner Peter Angelos and Angelos’ son, Lou, an ownership representative, adding to Anderson’s perceived power with the club – and prompting discussions among some players about what his continued ascent might mean for the club’s future management structure, sources said.

The bond between Anderson and the elder Angelos, dating back more than two decades, is at times useful to an organization in which communication often is difficult – Duquette said that Anderson serves as a “helpful” conduit to the owner, who is 86.

Duquette also cited Anderson’s overall impact as one reason the Orioles have won the most games of any American League club in the past five years, reaching the postseason three times.

Anderson assumed his current role a few months before Showalter took over as manager in July 2010 and more than a year before Duquette arrived in Nov. 2011. The team endured 14 consecutive losing seasons and frequent management turnover before starting its successful five-year run in ‘12.

But to some, the downside of Anderson’s status is that it creates the perception that he can operate freely without fear of being challenged.

“I like Brady. Everybody likes Brady,” former pitching coach Dave Wallace said. “But one of the problems is, when you have a role in an organization where you have total autonomy and really no accountability, that’s tough.”

Wallace, 70, and bullpen coach Dom Chiti, 57, both left Showalter’s staff after three years at the end of last season, in part due to what Wallace described as Anderson’s rising influence and interference.

Wallace said that he had planned to retire from major-league coaching, but that Anderson was part of the reason he resisted overtures to remain with the Orioles in a player-development role.

Chiti said, “I’m not going to deny that Brady was part of why I left,” but declined further comment.

Both Wallace and Chiti signed two-year contracts to return to the Braves, for whom each had worked just before joining the Orioles. Chiti became the Braves’ director of pitching, Wallace a special assistant who will focus on pitching.

Some players, too, are uncomfortable with Anderson’s presence.

Anderson last played for the Orioles in 2001, but he has a locker inside the team’s clubhouse at Camden Yards, where he gets into uniform to coach.

“A baseball clubhouse is always going to be something that players want to keep locked down as much as possible. That’s where it’s a fine line,” said former Orioles catcher Matt Wieters, who recently ended his eight-year tenure with the club by signing a free-agent contract with the Nationals.

“Brady was a great player for a long time. He was a member of that clubhouse. At the same time, when you get into the season, the 25 guys in that clubhouse are who you want in that clubhouse.

“It’s just a different situation there. It’s a former player who wants to be on the performance side as well as on the front-office side. It’s tough balancing the two.”

Some player agents have expressed concern to the Major League Baseball Players Association about Anderson’s role, and also have reported to the union that Duquette and Anderson sometimes communicate different messages to agents, sources said.

The union has made proposals in collective bargaining to prohibit direct contact between management and players, but those proposals have gained no traction, with clubs maintaining that they have the right to talk to their employees.

Anderson said that he never discusses contracts with players and rarely gets involved in negotiations with their agents, saying that part of his role is “the least of what I do, almost non-existent.”

He did help the Orioles re-sign a free agent in each of the past two offseasons – first reliever Darren O’Day, who was represented by Anderson’s former agent, Jeff Borris, and then outfielder Mark Trumbo. Anderson said that he also helps on occasion with minor-league free agents, and Duquette said that he assists with certain arbitration-eligible players as well.

Coaching, though, is a far more important to Anderson, who hosts both hitters and pitchers at his Los Angeles home every offseason for training and conditioning.

Even Anderson’s critics rave about his work in nutrition and conditioning; he hires all of the Orioles’ strength and conditioning coaches, majors and minors.

Anderson, who hit 50 home runs in 1996 and stole 53 bases in ‘92, remains among the Orioles’ all-time top 10 in a number of offensive categories. His 50-homer season triggered suspicions that he used performance-enhancing drugs, but those suspicions never were supported by hard evidence.

Anderson’s friend and former Orioles teammate, Cal Ripken Jr., told the Baltimore Sun in 2004, “Brady always had a much more advanced concept of cross-training and plyometrics and his diet. He was just ahead of the curve.”

Still is ahead, the way the Orioles the see it.

“He’s brought over a work ethic that I’d say we had, but now it’s magnified,” said Jones, a five-time All-Star. “Our nutrition side in the clubhouse has changed tremendously due to his influence. He got us a team chef that sometimes I steal her from him – she’s that good.

“That’s what he brought – the work ethic and nutrition, understanding that to play this game at a high level you just can’t sit there and eat McDonald’s and get away with it. He’s been a great source in that regard.”

***

Cubs right-hander Jake Arrieta, who pitched for the Orioles from 2010 to ’13, recalls Anderson’s work with the team fondly.

“He was all over the place when I was there – in a good way,” Arrieta said. “He was there at 1 o’clock (before a night game), training Wei-Yin Chen or myself – (Chris) Tillman, (Brian) Matusz, (Zach) Britton, Tommy Hunter – whoever it was. We’d dead lift. Do intervals on the speed bike. Then sprints on the hill, the ramp where our parking garage was.

“For BP, he’d be throwing to guys in the cage. He’d be in the outfield with the outfielders shagging at 100 percent. He’d have meetings with Buck, with Duquette. He was getting more involved on the front-office side. It was cool to see that. He felt like one of us, but he was also kind of on the business side.”

The Orioles parted with Arrieta in an infamous trade on July 2, 2013, sending him to the Cubs with righty Pedro Strop for righty Scott Feldman and catcher Steve Clevenger

Arrieta remains appreciative of Anderson’s help and support, saying he, “always came to my defense.” But the 2015 National League Cy Young award winner, who remains in touch with some of his former Orioles teammates, said that Anderson faces a delicate balancing act with players, some of whom inevitably will ask, which side is he on?

“There are certain objectives and motives that the players have and certain objectives and motives that the front office has. There is nothing wrong with that. It’s not a bad thing. It’s just the way it is,” Arrieta said.

“Sometimes, the relationship can be muddled by information that is withheld or information that is given to a certain guy that is not received in the best way. That’s just part of it. That’s why you have to be careful.

“You have to decide, which way do you want to go? Which side do you want to be on? Not that we’re on different sides. We’re all on the same team. But when you start talking business and contracts and things like that, it can get a little hairy.”

Or, as Wieters put it, “You want to be friends with everybody. At the same time, it’s a business. You’ve got to kind of figure out there are lines you can’t cross.”

Anderson, when informed of Arrieta’s remarks, repeated that his involvement in contract talks is limited, then referenced the O’Day discussions in Dec. 2015.

O’Day, a setup reliever, drew heavy interest from the Nationals before agreeing to a four-year, $31 million free-agent contract to stay with the Orioles.

Anderson said he agreed with Arrieta that it might be awkward for him to mix business and baseball, “but to me, not as awkward as Darren playing for the Nationals.”

“If that’s the worst thing that you can say, that I got involved with Darren’s contract . . . if that’s the criticism and a few players feel like that, I guess I have to think about that,” Anderson said. “I’m willing to accept fair criticisms.”

Both Anderson and Showalter, however, take strong exception to any suggestion that Anderson operates as a tool of management.

Showalter said the trust that Anderson builds with players is one of his greatest strengths.

“I want to have him in a role and to have a relationship with the players so they can feel anything they are telling him is not coming to me. And it’s not,” Showalter said.

“Brady is probably one of the most blatantly honest guys you’ll ever be around. That’s what I like about him. He doesn’t play any political (games). He’s got no agenda. He loves the Orioles, and he works his butt off.”

Showalter also downplayed the significance of Anderson maintaining a locker inside the Orioles’ clubhouse, saying that Anderson is so busy, “he’s hardly ever there.” The team also is considering building an office for Anderson in the training room/weight room area, Showalter said.

“We don’t look at him as front office,” Jones said. “We rarely see him in slacks or a polo. He’s always in something athletic. I know he’s a VP, but it seems like he’s an extra eyes and ears, an extra strength coach that is able to talk to you at any given moment.”

Anderson said his locker was, “just a place to get dressed,” noting that his return to the organization preceded the arrivals of most of the Orioles’ current players.

Are the players aware of his relationships with Peter and Lou Angelos?

“Sure,” Anderson said. “Lou comes in the clubhouse all the time. Obviously, the owner hired me. He’s the ultimate boss. Everybody knows it. It’s like saying, ‘Am I aware of Adam’s relationship with Peter?’”

Initially, when I asked Anderson if the players were comfortable with his role, he said he didn’t understand the question.

I rephrased it.

“When you were playing, if there was a guy dressing in the clubhouse who was vice president of baseball operations, a member of the front office who had a good relationship with the owner, would you have been comfortable around that person?” I asked.

“It’s an unusual case, I admit,” Anderson said. “I don’t know what to say. We’ve had huge success during the time (that he has been in this role). To a high degree, I’m pro-player. I’m private individually. I don’t betray trusts ever. That’s not a problem.

“You’ve been around baseball. There are third-base coaches and people who have relationships with owners. There are all sorts of people who are known as spies or whatever.

“It’s just not applicable to me. It just doesn’t exist.”

Anderson’s conflicts with coaches, however, are quite real.

***

Right-hander Mike Wright joined the Orioles in May 2015 and was an immediate sensation, working a combined 14 1/3 scoreless innings in his first two starts.

After that Wright struggled, producing an 8.90 ERA over his final 30 1/3 innings – and eventually becoming a flashpoint in the discord between Anderson and the Orioles’ pitching coaches at the time, Wallace and Chiti.

“(Anderson) just steps in everywhere,” said Wallace, who was the pitching coach for the 2000 National League champion Mets and 2004 World Series champion Red Sox, plus at different points with the Astros and Dodgers.

“That’s OK. He’s knowledgeable and he knows baseball. But there’s a way to get information to major-league players. With coaching experience, you learn how to do that pretty successfully.”

Anderson’s issues with coaches are not exclusive to the major-league club. Orioles minor-league staffers, speaking on condition of anonymity, said Anderson will work with minor-league players, then inform coaches that a player is “fixed” without revealing the changes that he instructed the player to make.

Duquette said that Anderson maintains the autonomy to work with any hitter or pitcher in the majors and minors, provided that he reveals his plans first. Anderson said he always communicates with coaches, explaining, “You have to be upfront with everything. You can’t be sneaking around, because that’s destructive. Everything has to be out in the open and positive.”

Showalter, too, said that Anderson is open in his communication. Wallace, however, describes an “us-vs.-them” wedge that Anderson occasionally drives between the players he works with and their coaches.

Wright was one example.

As Wright struggled in 2015, Wallace said that he and Chiti suggested a number of adjustments to the pitcher, including moving toward the third-base side of the rubber.

“Mike was a little hard-headed about it. Which is OK. I’ve had many players like that,” Wallace said. “But the next spring we come to camp, and we’re summoned to a meeting with Brady. And Brady tells us how we mishandled Mike Wright.

“Mike had gone to Brady’s house in California (during the offseason) and I’m sure said some things that weren’t very complimentary of Dom and I. Which is OK. It doesn’t have to be perfect. By the same token, you can come to us. We tell the players all the time, ‘You can ask us why. Tell us if you disagree. We don’t force you to do anything. We make suggestions.’”

Wright said that he spent a month at Anderson’s home during the 2015-16 offseason, joined at various points by other young Orioles players (Britton and Tillman are among the Orioles who stayed and trained with Anderson early in their careers).

“He likes to work with younger guys, kind of speed (up) their big-league process,” Wright said. “I threw probably four or five bullpens through the month of January, mostly just fastballs. Obviously, he wasn’t a pitcher. But he has seen a lot of good pitchers. And he studies the game. He knows a lot about it.”

Wright said that during the season he worked with the Orioles’ pitching coaches, but that Anderson was always available in the weight room to talk. Without specifically indicting Wallace and Chiti, Wright added, “If you get somebody else saying something a different way, sometimes that’s all you need. I felt like Brady and I were really on the same page at a time when I kind of needed it.”

Wallace, though, considers Anderson’s approach counter-productive.

“One of the keys to being a successful coach – and I’ve been a pitching coordinator for many years – is to go into the pitching coach at that affiliate and you say, ‘OK, we’re going to see Player X. What have you done with him? What’s going on? Give me your input.’

“Then you embrace the coach in front of the player so the player looks and sees that you two are together for his best interest. Ultimately, our responsibility is to make the players better. And in today’s world, if the players see you two together . . . you can disagree behind closed doors, but it’s all in the approach. That’s where I think Brady needs more experience.”

Many Orioles pitchers hold Wallace and Chiti in high regard; Britton and fellow All-Star reliever Brad Brach spoke out strongly in support of the two coaches after they departed.

Duquette, however, indicated that he was frustrated with the internal strife, mentioning Wallace and Chiti, unprompted, when asked if coaches generally were comfortable working with Anderson.

“Wallace and Chiti pissed on him for a couple of things they didn’t really like . . . they were critical of how Brady operated within the organization,” Duquette said. “But Brady was working on behalf of the organization. And those guys are not with the organization anymore.”

Wallace took exception with Duquette’s remarks, saying, “Everything we did with Brady, we talked to Brady about . . . I liked him. We disagreed. Big deal.”

Anderson, meanwhile, said that he wanted Wallace to return as pitching coach and that he admired Chiti, saying, “I probably liked Dom more than he liked me.”

But at one point, Anderson said, “There’s one thing I won’t tolerate, and that’s a coach who is being dismissive of a younger player. If there is any conflict that has ever happened, that would have been the cause.”

He grew animated taking about Wright.

“When you change movement patterns in an elite athlete – an elite athlete, not a 12- or 13-year-old . . . certainly Mike Wright is an elite athlete. Suggestions are good, but the athlete has to believe what he’s doing is right,” Anderson said.

“When you change a person, you’ve got to make sure you do it without creating any doubt. It’s imperative. Jake (Arrieta) is the perfect example. We let the best pitcher in the entire world get out of our hands because they (Wallace’s and Chiti’s predecessors) created doubt in his head, or somehow it was created. I’m not saying they did it, that anyone said intentionally, ‘I’m going to put doubt in you.’ But that crept in. I’m super-sensitive to that.”

Anderson once was in such a position himself.

***

In the book, “Moneyball,” author Michael Lewis details how Billy Beane’s upheaval of the Athletics’ scouting operation was rooted in the scouting community’s failure to properly evaluate him as a player.

Beane, coming out of Mount Carmel H.S. in San Diego, was the Mets’ first-round pick, 23rd overall, in 1980. But he batted only .219 in only parts of six seasons with four different clubs, and by 27 was out of the game.

Anderson’s perspective on coaching comes from a similar place. Wallace said that Anderson makes no secret that he has little respect for major-league coaches, and added that he has told Anderson that to his face.

Unlike Beane, Anderson was a relatively low draft pick, the Red Sox’s 10th-round selection out of Cal-Irvine in 1985. Also unlike Beane, Anderson enjoyed significant minor-league success, rocketing through the Red Sox’s system prior to his trade to the Orioles.

Anderson said his desire to see young players “put on the proper path” stems from his frustration with his own development.

“I came up through the minors basically untouched. And then started the progression being changed to what people perceived me to be,” Anderson said.

“I don’t think they were trying to harm me. I know they weren’t . . . Some of the advice was just so poor. It could have easily ruined my career. I see guys like that all the time.”

The Red Sox, Anderson said, would not allow him to bunt. Later, when he reached the majors with the Orioles, he was asked only to bunt and hit to the opposite field. During his first four seasons, from 1988 to ’91, he batted only .219, shuttling between the majors and minors.

“It was a constant, taking something that had been natural to me and making it unnatural,” Anderson said.

His breakthrough came in ’92, when the late Orioles manager Johnny Oates named Anderson his leadoff hitter and turned him loose. The results were stunning: Anderson batted .271 with a .373 on-base percentage, 21 home runs and 53 steals.

Today, the players Anderson gravitates toward most are the players who remind him of his old self, players seemingly on the verge of losing their careers. Showalter said that his only problem with Anderson is that he, “tries to save ‘em all.”

“A lot of times I’ll get players when they’ve hit rock bottom in their minds,” Anderson said. “Those are times when people sort of leave ‘em. That’s when I emerge, I guess.”

Anderson said he will tell struggling players that they should aspire to be not simply role players but stars, recalling a specific talk he had with Britton to that effect before the left-hander became one of the game’s top closers.

Much to Anderson’s surprise, he gets a thrill out of helping players improve; he never imagined that he would coach during his playing days, though his father told him he had a gift for it.

He only stumbled into coaching after he retired when former Orioles teammates started reached out to him for help. Infielder Jerry Hairston Jr. was one of Anderson’s first triumphs, rebounding from two dismal seasons with the Rangers to bat .326 with the Reds in ’08.

“He was a major reason why I had success from ’08 to ’13,” Hairston said. “He revamped my swing. He was awesome.”

Teaching hitting is one thing – Anderson excelled at that skill at the game’s highest level. But pitching? Anderson said he was a starting pitcher at Carlsbad (Ca.), H.S., a No. 1 starter who pitched in playoffs. But he never threw a single pitch in 2,217 games in the majors and minors.

“The argument about me working with pitchers – I have a track background. I have an early analytics background. My mind is scientifically oriented,” Anderson said.

“I’ve been studying movements for 30-plus years, whether it’s a javelin thrower, a baseball thrower, or a hitter or a golfer. They all have to do certain things right in certain sequences. And you have to be able to get them to do that.

“ . . . I have deficiencies in life, a lot of ‘em. But watching athletes move is not one of them. Breaking down their movements, that’s not one of my problems. How you leverage yourself, how you generate power, these are strengths of mine and I’m going to use them, regardless of a player’s position.”

***

At one point during our conversation, I asked Anderson, “Who are you responsible to? Whom do you report to?”

“Who does Buck report to?” Anderson asked.

“Dan, but also Peter,” I replied.

“Who does Dan report to?”

“Peter.”

Anderson paused before continuing, then said he viewed his efforts as part of a collaboration. He offered individual praise for Showalter, Duquette and Peter Angelos, calling the owner, “one of the best people I know, one of the best characters, somebody I’m intensely loyal to, always will be.”

“Of course I report to Peter ultimately – he’s the boss,” Anderson said. “But Buck told me he didn’t like the infield one day at Triple-A. So I got in my car and drove four hours to Norfolk to talk to the groundskeeper. I don’t care. Anybody can give me an assignment. I’m happy to do it. There’s nothing too small or too large I won’t do to help the team.”

I posed the same question to Duquette: Who does Anderson report to?

“I wouldn’t say that he technically reports to me or Buck,” Duquette said. “The owner had hired him before I had gotten here, and the owner hired him directly.

“Brady’s been around. I think he respects the office of the manager and the general manager. But I don’t know that he reports directly to Buck or I.”

However atypical the arrangement might appear, the Orioles routinely thrive on the field despite unusual internal politics, consistently outperforming their PECOTA projections.

The team’s management structure endured after Duquette unsuccessfully sought to become Blue Jays team president during the 2014-15 off-season; the two clubs could not agree on compensation.

The structure also endured after tension surfaced between Showalter and Duquette at the end of ’15, with one club official telling me at the time, “If it doesn’t change, it will be a disaster.”

Both Showalter and Duquette are signed through ’18; an extension for Showalter, in particular, would not be surprising if he wants to continue managing. Otherwise, he eventually could replace Duquette as GM; there was media speculation that Showalter and Anderson would have assumed additional front-office duties if Duquette had left for the Blue Jays.

Showalter, criticized during past managerial stops for being overly controlling, has taken a pragmatic approach to Anderson’s ascension, according to sources.

While Showalter occasionally advises Anderson on organizational protocol, the manager recognizes that he stands little to gain by clashing with a VP whom is often helpful and close with ownership, sources said.

Turnover in the pitching coach’s position, meanwhile, is not exactly unusual for the Orioles. Roger McDowell, the replacement for Wallace, is the team’s sixth pitching coach in the nearly seven years since Showalter took over.

McDowell, the Braves’ pitching coach from 2006 to ’16, credits Wallace with teaching him the position during their time together in the Atlanta organization.

New bullpen coach Alan Mills, who was a teammate of Anderson’s with the Orioles from 1992 to ’98 and 2000-01, spent five years as a coach in the Orioles’ system, the past two at Double-A.

Coaches come and go. The bigger question for the Orioles is Anderson’s future – what it might be, what it might mean for the organization.

“I want to be the best at what I’m doing, while I’m doing it,” Anderson said. “If my role changes . . . I don’t know if this is a quality or a detriment for me, but I’m not on some path to somewhere else in this career.

“I could be. And I think about it. I’m not blind to the idea of being a GM one day. But that’s not needed here. We have one. My feeling is, if I do my job really well, we can keep our GM forever, our manager forever, our players together. That would be the ultimate for me.

“It could be unrealistic. But that’s how I go about it.”