SCOTTSDALE, Ariz. — Look how cute, the 5-year-old boy wearing a Walter Payton shirt with a plastic helmet and pads, stiff-arming his little playmates the way Sweetness did.

His only dream was to be a football player. Growing up in Indiana, he wanted to wear the green of Notre Dame, then become a Chicago Bear.

Jeff Samardzija lived half the dream, becoming an All-America receiver, catching passes and setting records in South Bend. He could have been in the NFL, could have stared down and raced past defensive backs in front of 70,000 howling fans in one of sport’s most intense atmospheres.

Football lost and baseball won.

Samardzija gave up the boyhood quest. He let Walter Payton go. Not because he worried about head injuries. Who did in those days? Not because of money, because Lord knows there’s plenty of green in football. Not merely because he could pitch a baseball at 98 mph.

When you are 16 and your mother dies, your brain is jolted. It tells you that life is too precious to waste doing anything for the wrong reasons, that you have to do anything and everything in your mortal power to chase happiness.

For Jeffrey Alan Samardzija, the decision was easy.

He simply liked baseball more.

“My mom could live how she lived and something crazy happened to her,” Samardzija said. “I wasn’t going to waste time doing things I didn’t want to do.”

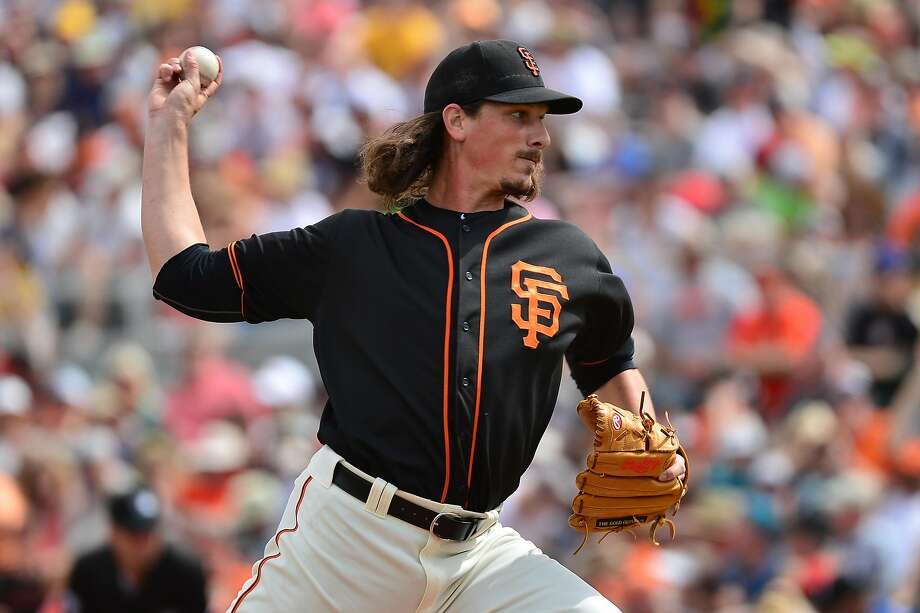

Now 31 and nine years removed from the most important decision of his life, Samardzija brings his 6-foot-5 frame, high-90s fastballs and a resume that screams “talented but inconsistent” to San Francisco, his new home for five years after signing a $90 million contract in December to start for the Giants.

Samardzija did not turn his back on football as much as he embraced baseball, a more cerebral game.

“I liked the freedom of baseball,” he said, “the free-thinking of it, and how many different ways there are to skin a cat in this game.”

The revelation came in the strangest place, on the desolate highways and byways of the Northwest, after the Chicago Cubs drafted Samardzija and sent him to their rookie-level Class A team in Boise, Idaho, after his junior year of college. The rules allowed him to return to Notre Dame and play football as a senior.

He sat on buses for nine-hour trips, awful, monotonous journeys to play before sparse crowds on sometimes awful fields, yet he liked that more than the thought of sitting through Wednesday morning football meetings and the monotony of practice.

Samardzija was fortunate to play for coaches at Notre Dame who put his happiness ahead the program, who let him pitch on Saturdays after spring football practices ended Friday and ultimately advised him that baseball represented his best future.

“I would have loved to see him play in the NFL, but the way things have gone in his career, I think he made the right choice,” said Charlie Weis, the head football coach at Notre Dame in Samardzija’s final two seasons.

“He was a football-playing dude, an offensive player who would do a lot of trash talking. I absolutely loved him.”

Before Samardzija signed with the Cubs, Weis asked him if his contract would be guaranteed, unlike a big chunk of NFL deals. When Samardzija said yes, Weis told him to sign.

One of the first people Samardzija called after he decided to forgo the 2007 NFL draft was his first Notre Dame coach, Tyrone Willingham, who allowed him to be a two-sport athlete, so rare now in big-time college sports.

“For me, it’s simple, career longevity, baseball versus football, if you’re good at it, and obviously he’s good at it,” Willingham said. “You can have a career that lasts 20 years. Very few football players can have that kind of career.”

If Samardzija’s father had his way, Jeff might be in the NHL. Sam Samardzija was a semipro hockey player, but his kids could not find much ice time in their Indiana hometown and Jeff did not learn to skate. He laughed at what he might have become at his size, “an enforcer with a big slap shot.”

His mother, Debora, died in 2001 from an infection related to a respiratory illness. How does a 16-year-old process that? How does he move forward?

Sports was a huge release. He also tried to pick her brain even after she was gone.

“I know for a fact there wouldn’t be one day that my mom would want me to be sad that she wasn’t around anymore, because that was just her personality,” Samardzija said.

“So selfless. She wouldn’t want the burden of me having a bad day because she left us unfortunately too early.”

Samardzija has had a lot of bad days in baseball. Many good ones, too, talented enough to be an All-Star for the Cubs in 2014, terrible enough to allow a league-leading 228 hits, 118 runs and 29 homers for the White Sox last year.

The Giants saw beyond those numbers when they handed Samardzija $90 million. Their vision was a powerful sinker-slider-splitter pitcher who got a lot of groundballs in front of the worst defense in the majors, who wilted in yet another losing situation and might thrive in the home of three World Series banners.

Except for a brief stint with the A’s in 2014, Samardzija largely pitched for lousy teams on both sides of Chicago, forced to learn the importance of treating every game as critical even if it wasn’t.

“We weren’t good in the 2½ years when we were with him,” said Cubs general manager Jed Hoyer, who assumed the job before the 2012 season. “He always pitched his best for us in big games, so to speak. We didn’t have a lot of them. He was always brilliant when he pitched Opening Day, or facing the White Sox, or a national TV game.

“We weren’t capable of giving him the stage he deserved. That was hard.”

Samardzija learned from experienced Cubs teammates such as Ryan Dempster and Ted Lilly how to pitch with fire even when postseason aspirations were under water.

“Don’t get me wrong,” he said. “I’d definitely rather the lights be bright and the stands be packed.”

Samardzija could have had that every week in the NFL. Don’t the Jacksonville Jaguars and other bottom-feeders fill their stadiums every Sunday?

He surrendered his boyhood dream, the sport that consumed him even as a tot, to play baseball, the game he learned to love more.

“I loved that the competition of football that was so in-your-face,” Samardzija said. “You’re face to face with the guys you’re playing with the whole time. There’s a certain respect level. Baseball’s a little different where you’re 60 feet from the guys you’re playing against at all times.

“I understood that giving up those games, I would never get them back because, in basketball, or baseball, you can go play pickup games until you’re 40 or 50 or 60 years old. In football, there’s no pickup football games. You can only play in organized football, and if you’re not in that circle you ain’t going to play.

“I knew I would miss it, but I had given a lot of my time to football.”

The way this onetime Walter Payton wannabe laughs and buzzes through the Giants clubhouse even a decade removed from those marathon Idaho bus rides, nobody can doubt he made the best choice.

Chronicle staff writer

Susan Slusser

contributed to this report.

Henry Schulman is a San Francisco Chronicle staff writer. Email: hschulman@sfchronicle.com Twitter: @hankschulman