I was a horrible lacrosse player in high school: bad at catching the ball, slow, and not very aggressive.

Yet I’d spend hours at a handball wall with my stick: throwing, catching, repeating. I played on winter leagues, and woke up early for 6 am pickup games. Freshman and sophomore years, I made it on to the junior varsity team — a miracle.

By 11th grade, it was time to try out for varsity lacrosse. This is when my history teacher — the varsity coach — pulled me aside and suggested I shouldn’t bother. I’d probably be cut, he said (adding that I was getting very good grades).

For me, practice did not make perfect. Lo and behold, I now have scientific validation.

A new meta analysis in Perspectives in Psychological Science looked at 33 studies on the relationship between deliberate practice and athletic achievement, and found that practice just doesn’t matter that much.

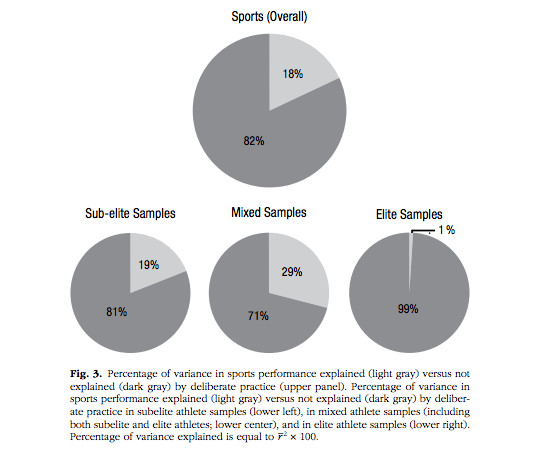

More precisely, the analysis found, practice can account for 18 percent of the difference in athletic success. Put another way, if we compare batting averages between two baseball players, the amount of time the players spent in the batting cage would only account for 18 percent of the reason why one player’s average is better than the other.

Even more simply: Some people are just better at sports than others, and the difference cannot be made up by practice alone. There was reason why I lagged behind my peers on the lacrosse field. They probably had a natural advantage on me.

“One important thing — that’s easy to misunderstand— is that this is looking at variance across people, not within an individual,” Brooke Macnamara, the lead author of the new paper, tells me. “So if a person practices, they will get better. Almost across the board, practice should improve one’s performance.”

But it also means for the same amount of practice, some will end up being better at sports than others. “Essentially, learning rates vary,” Macnamara says. “Some people improve very quickly with less practice while others require much more practice.”

The analysis found this 18 percent figure is roughly true no matter what’s type of sport is being played. Practice accounts for the same difference in performance in bowling as it does field hockey, two completely different activities.

Practice also explains fewer differences in ability the further an athlete ascends into higher levels of play. Which suggests “deliberate practice loses its predictive power beyond a certain level of skill,” the study reports. The analysis also found that the age when athletes started their sports didn’t change this figure much either.

So what, then, explains the remaining 82 percent?

Here’s where we should note a limitation of studying practice: Researchers typically ask athletes to recall their schedules and practice hours, and memories can be faulty.

But Macnamara doesn’t think better measurements of practice would make that 18 percent figure leap up to near 100.

“There’s probably not one huge contributor that’s accounting for everything else,” she says.

Instead, there’s likely a whole constellation of factors — some of which are genetic or biological in nature — that explain why some people are better athletes than others. They include:

- Personality and perseverance

- Propensity to get injured

- Propensity to choke under pressure

- Individual differences in maximum oxygen uptake

- Differences in how we acquire muscle mass

- Coordination

- Height

- Enjoyment of competition

“We have so many factors within a person that can contribute to [athletic performance],” she says. “Different genes, different cognitive abilities, different physical attributes. All of those things are important and interact with each other. Which is why it is so hard to pin down what predicts performance.”

Overall, she says the finding is a strike against the popular “10,000 hour rule,” which implies anyone can become master at an activity if they were to just devote the time to it. The research in sports, and in other activities such as music, games, and education, just doesn’t back that hypothesis up.

On the other hand, it’s not like these findings are an excuse to not try.

“18 percent is big,” Macnamara says. “We’re trying to argue against these ideas that it’s so important it accounts for nearly everything.” Practice matters, but it’s unlikely to bridge the gap between inborn superstars and your average, or perhaps clumsy, kid.

For the athletically un-inclined, like myself, it’s a bit of a relief. It’s okay if you can’t make up the difference with practice, or if you’re just a “slow learner” when it comes to sports. It’s also okay to just enjoy being on a team, trying hard, but knowing you’ll unlikely be the best.

Growing up, my dad was on a quest to find “my sport” — the activity I’d finally master. Lacrosse was the closest we came. But it mostly a parade of failures. Baseball: Throw a ball at me and I’ll be more likely to bruise than catch it. Soccer: I was much too slow. Basketball: All of the above. Tennis: I was cut from the middle school team.

I’m not a well-coordinated person, and that’s just fine.

These days I stick to activities that don’t involve hand-eye coordination: hiking, biking, running, skiing. I love physical activity. Life’s just too short to spend it on activities you’re horrible at.