Sign-up now to receive a free download of the new O’Reilly report “Data Analytics in Sports: How Playing with Data Transforms the Game” when it publishes this fall.

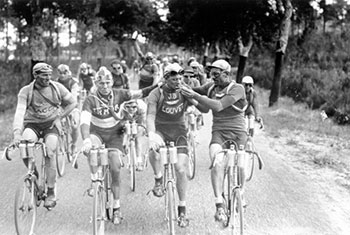

Julien Vervaecke and Maurice Geldhof smoking a cigarette at the 1927 Tour de France. Public domain photo via Wikimedia Commons.

One of my favorite books from the last few years is David Epstein’s engaging tour through sports science using examples and stories from a wide variety of athletic endeavors. Epstein draws on examples from individual sports (including track and field, winter sports) and major U.S. team sports (baseball, basketball, and American football), and uses the latest research to explain how data and science are being used to improve athletic performance.

In a recent episode of the O’Reilly Data Show Podcast, I spoke with Epstein about his book, data science and sports, and his recent series of articles detailing suspicious practices at one of the world’s premier track and field training programs (the Oregon Project).

Nature/nurture and hardware/software

Epstein’s book contains examples of sports where athletes with certain physical attributes start off with an advantage. In relation to that, we discussed feature selection and feature engineering — the relative importance of factors like training methods, technique, genes, equipment, and diet — topics which Epstein has written about and studied extensively:

One of the most important findings in sports genetics is that your ability to improve with respect to a certain training program is mediated by your genes, so it’s really important to find the kind of training program that’s best tailored to your physiology. … The skills it takes for team sports, these perceptual skills, nobody is born with those. Those are completely software, to use the computer analogy. But it turns out that once the software is downloaded, it’s like a computer. While your hardware doesn’t do anything alone without software, once you’ve got the software, the hardware actually makes a lot of a difference in how good of an operating machine you have. It can be obscured when people don’t study it correctly, which is why I took on some of the 10,000 hours stuff.

…

You might think Usain Bolt moves his legs fast, but he actually repositions his legs at the same rate as your grandmother when she’s running as fast as she can, or maybe your mother if your grandmother is a little older. Sprinters don’t win by moving their legs through the air faster. They win by putting five times their body weight into the ground as fast as humanly possible. … Literally, sprinting is limited by the contractile speed of the muscle fibers, so you need a lot of those fast twitch muscle fibers. … There’s a lot of longitudinal data with tens of thousands of people who are tracked longitudinally that show that, whether you like it or not, slow kids do not become fast adults. … Speed is slightly predictable in a broad sense.

Market efficiency

As in finance and other domains, innovations only remain proprietary for a limited amount of time. For one thing, athletes, trainers, and sports scientists bounce around between organizations and bring ideas along with them, but also breakthroughs can be observed and reverse-engineered. To some extent, this means that athletes and teams start looking alike (as I lamented in our conversation, there is a trend toward hyper-specialization — for example, most NBA teams employ players adept at shooting “corner threes”). Epstein cited a recent example:

There’s a really funny example of that happening in a sport called skeleton, which is one of those new sports where innovation makes a huge impact. It’s a winter sport where people slide face-first down an icy track. … Everyone used to use two hands on the sled, then you run with it and you jump on it. This [British] coach was worried that the Americans had better equipment and were going to destroy his team. … These [British] guys basically invented the one-hand start. They had been training a certain way for several years. He gave them two hours to just go be creative, whatever. Do something stupid. They come back asking, ‘Is it within the rules to do it one-handed?’ He looked; it’s not against the rules. They keep it secret, and when they broke it out, they broke the start world records left and right. Then everybody started using it right away, so it literally overnight transformed what everyone does in this sport.

Pattern recognition using estimates and “cheating”

As a longtime Tour de France fan, I’ve noticed that a group of fans and longtime watchers have taken to estimating various factors, like power output. Oftentimes, they compare an array of metrics that riders have generated in recent editions of the tour to similar metrics from the “doping era.”

Teams and officials previously labeled their efforts as pseudoscience, only to backtrack when it turned out that their power output estimates were extremely accurate. Using their own data and calculations, cycling fans are, in essence, using comparative and longitudinal studies to flag suspicious performance numbers. This has led to calls for teams and riders to provide more transparency by supplementing biological passports with the release of “training and racing log files.”

As Epstein noted, this type of comparative data would be insufficient in a court case, and in many situations good old-fashioned investigative journalism (sources and leaks) is what ultimately exposes cheaters. Nevertheless, it’s still good to see cycling fans engage with and pressure teams and race organizers, to release more data:

In those past eras of doping, like in the Lance Armstrong era, you look at what happens when the EPO test comes in and suddenly power outputs plummet. This year, in some cases, they look like they’re back to where they were after that. It’s not like guys had stopped training hard; they stopped doing EPOs. That sport for sure has earned the suspicion it gets. We have to be careful because the bicycles are improving, the weather changes — there are a lot of variables. But with the history of the sport and the fact that they were calling measurements that turned out to be quite accurate ‘pseudoscience,’ I think if they’re complaining about people being gadflies, that’s crazy. … It’s truly interesting, too, which sports the fans and enthusiasts engage with in that way.

Epstein pointed out that cheating can turn off fans, and it also makes comparative and longitudinal studies difficult to do:

People used to say women are going to catch up on men when they have more opportunity, but actually men are pulling away now. The gap is widening. I think it’s partly because a lot of the women’s records are stuck. Steroids, which are just testosterone analogues, have a much greater effect in women than they do in men. … We know in the past, there was this era of mega-doping. All these documents have now come out related to East Germany, and there was this very systematic, enormous amount of doping, so tons of women’s records are stuck and nobody even gets close to them most of the time. It’s a bummer.

You can listen to our entire interview in the SoundCloud player above, or subscribe through Stitcher, TuneIn, iTunes, or SoundCloud.

For more, watch David Epstein’s 2014 Strata + Hadoop World keynote: Small Data in Sports or listen to my conversation with Rajiv Maheswaran on the science of moving dots.