Rich get richer in college sports as poorer schools struggle to keep up – ABC News

The nation’s richest athletic departments — those in the Power Five conferences — pulled in a record $6 billion last year, nearly $4 billion more than all other schools combined, according to an Outside the Lines analysis of NCAA data. The gulf between college sports’ haves and have-nots has never been greater.

Powered by multimillion-dollar media rights contracts and rising ticket-sales revenue, the richest schools have spent aggressively: on private jets, on campus perks like barber shops and bowling alleys, on biometric gadgets for athletes, and on five-star hotel stays during travel. They’ve also hired a plethora of athletic department support staffers who earn six-figure salaries and sometimes have obscure job titles such as “horticulturalist” and “museum curator.”

To keep up, smaller conference schools — dubbed the Group of Five — are spending, too, but from different sources: Those schools have increasingly shifted hundreds of millions of dollars from students, taxpayers and other university programs into their athletic programs to do so, the analysis shows.

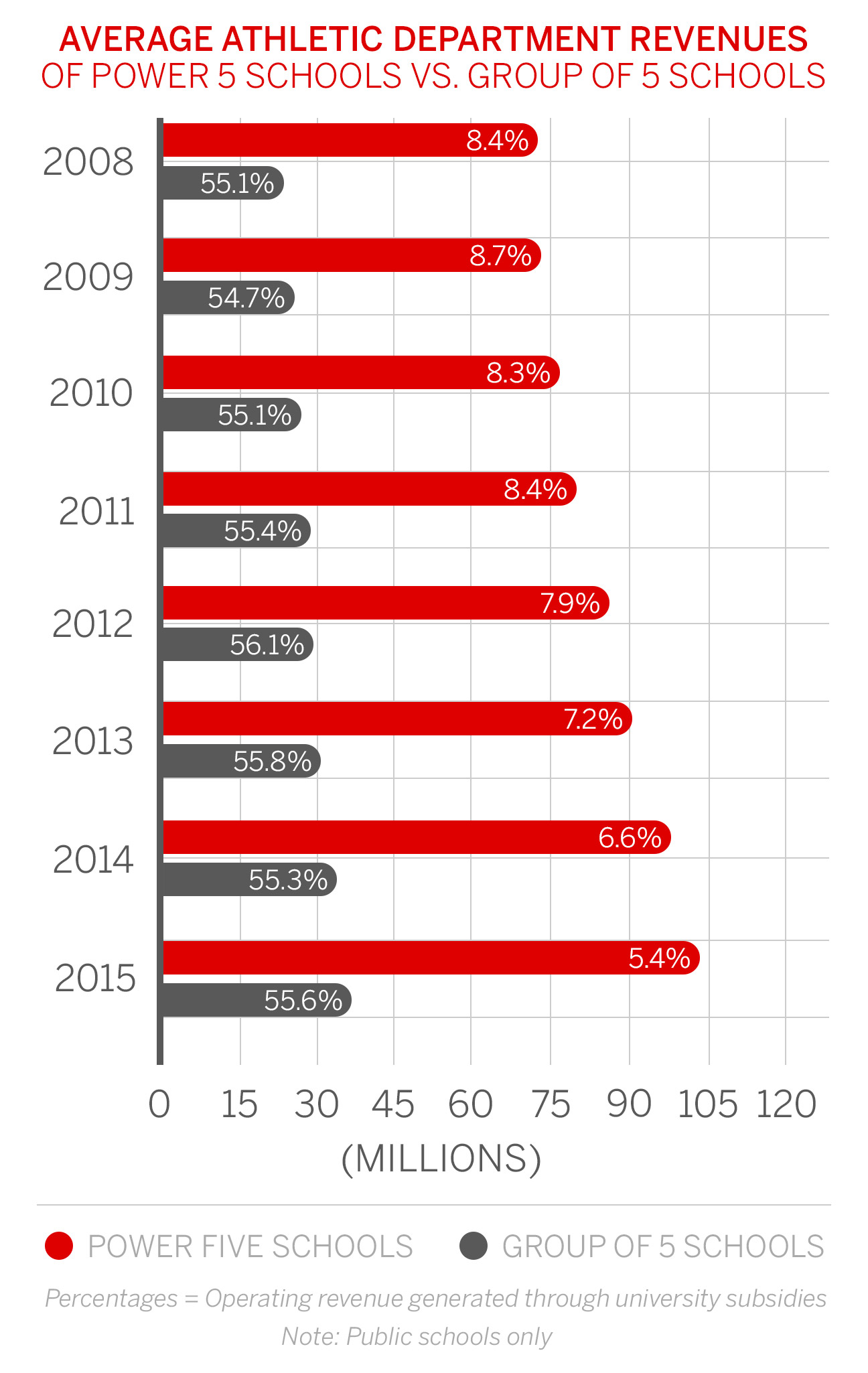

The Outside the Lines analysis examined eight years of revenue and expense data from all Division I/Football Bowl Subdivision schools. On average, Power Five and Group of Five schools each saw about 50 percent increases in net revenue during the eight-year period. But half of the revenue for public school athletic departments in the Group of Five came from student fees, university subsidies and state or local governments, even in the face shrinking state budgets. For Power Five schools — those in the SEC, Big 10, ACC, Big 12 and Pac-12 — subsidized sources made up just 5 percent of their budgets.

Richard Vedder, director of the Center for College Affordability and Productivity in Washington, D.C., said students often have no idea how much of their student fees bill goes toward sports: “They are aghast, ‘My God, I only went to two football games when I was in college. They cost me $500 apiece.'”

Other findings from the analysis:

- Texas A&M reported about $193 million revenue, the most of any Division I school, in 2014-15. The Aggies vaulted to the top spot because of donations received for the renovation and expansion of Kyle Field.

- The University of Texas had the highest ticket sales revenue, at $63.3 million, followed closely by Ohio State at $63.1 million, in 2014-15.

- Georgia and Alabama each spent $1.3 million on football recruiting in 2014-15, putting them at the top among Division I schools.?

- Ohio State spent the most on coaching salaries — a total of $28 million — in 2014-15.

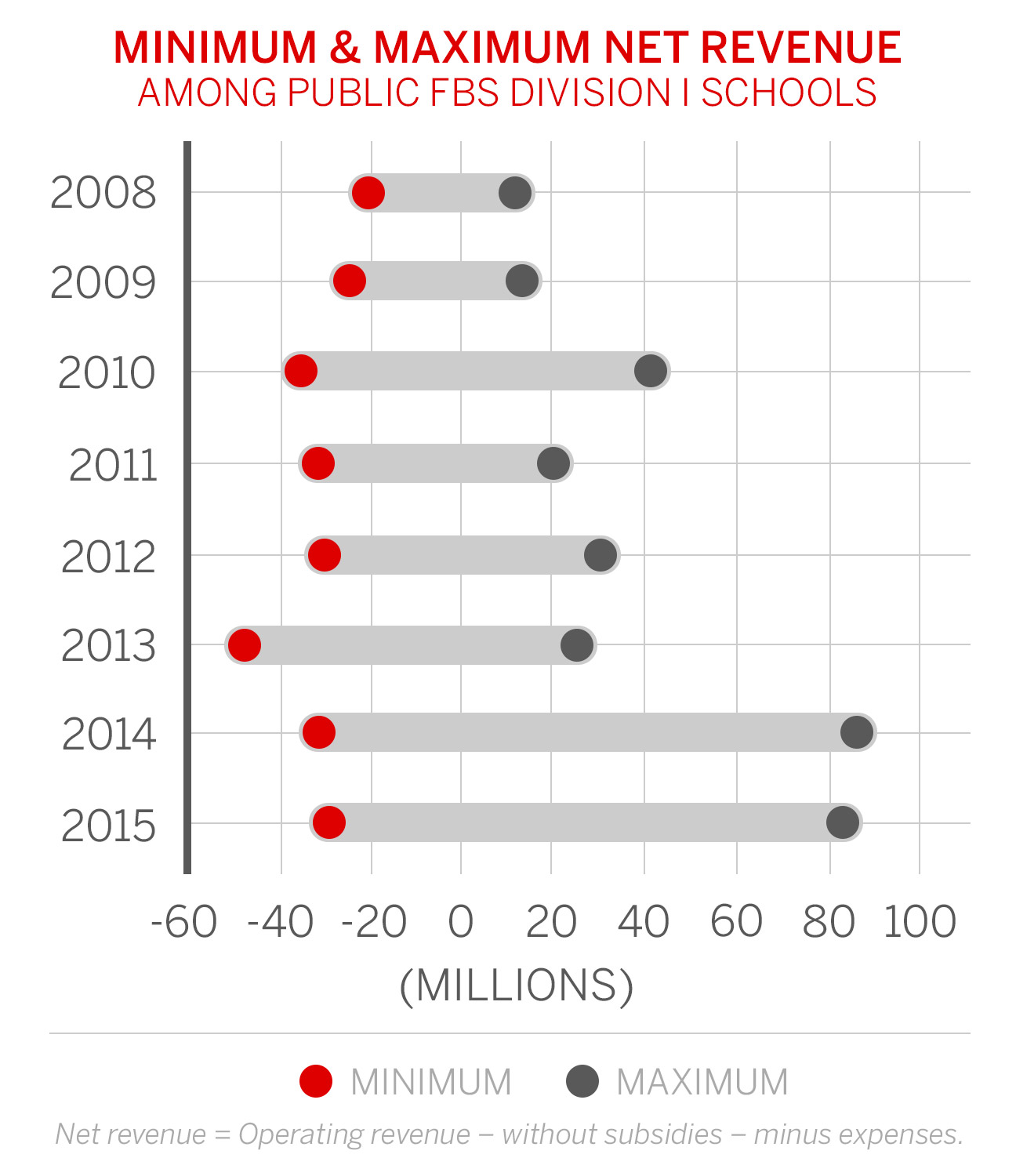

NCAA officials often argue that only two dozen or so of the 350 Division I athletic departments are truly self-sustaining, meaning revenues exceed or break even with expenses. But in recent years, college presidents and athletic directors have acknowledged that many athletic departments don’t show a profit or any excess carryover because there is no reason for them not to spend the money they earn. A few athletic departments do divert some revenue to their respective university budgets, but a Chronicle for Higher Education analysis this year found that only 10 athletic departments gave enough money back between 2011 and 2014 to offset what they had received in subsidies. Six of the 10 had received no subsidies.

An NCAA spokeswoman declined to comment, saying that “financial decisions are made at the campus level.”

The Outside the Lines analysis shows that the disparity between the richest and poorest schools has never been greater. In 2008, the gap between the average overall revenue of schools in today’s Power Five conferences and those in the Group of Five was about $43 million. In 2015, it was $65 million. For public schools, if subsidies are subtracted from that revenue, the gap gets even wider, from an average $53 million in 2008 to $83 million in 2015.

The Group of Five schools — whose combined revenue of $2 billion is just a third of their elite peers — have tried keep up with the Power Five schools by adding staff and increasing salaries to lure the best administrators and coaches, by building multimillion-dollar stadiums and arenas, and by giving athletes more money to cover tuition and living expenses.

The University of Connecticut is one example. Although its $72 million in operating revenue in 2015 put it higher than a number of Power Five programs, the American Athletic Conference school with its top-ranked men’s and women’s basketball teams pulled $28 million of that revenue from student fees and university subsidies — an amount that has more than doubled since 2008. Since then, revenue from ticket sales and contributions has decreased, according to data UCONN reported to the NCAA. Officials from the UCONN athletic department did not respond to a request for someone to be interviewed for this story.

This fall, returning UCONN students are facing a 6.7 percent tuition increase, part of a plan university regents approved last year to raise tuition by 31 percent over the next four years to help close a $40.2 million budget deficit.

Andrew Zimbalist, an economist at Smith College and a sports-business expert, is among many academics who say trying to keep up isn’t worth it.

“It’s violating the spirit of what college athletics are supposed to be, and financially it’s very destructive,” he said. “You can take $20-to-$30 million and give scholarships to poor minority kids who show academic promise in the inner city. That would show a greater impact on society and diversity and academic quality of the student body. I don’t think anybody would object to the athletic enterprise if they had a deficit similar to the deficit in the theater department or the classics department.”

Not all schools are chasing the Power Five dream, though: This past spring, the University of Idaho became the first school to leave the Football Bowl Subdivision, citing finances as one of the driving factors. The University System of Georgia Board of Regents recently enacted a rule that limits how much money from student fees and tuition can be spent on athletics, and last year the Virginia Legislature made a similar move.

Similar efforts have been met with significant resistance, though. The University of Alabama-Birmingham announced in fall 2014 that it would eliminate football because officials said it cost too much to subsidize, but the decision was met with such fierce opposition that the school reinstated it this year and plans to start conference play in fall 2017.?It is also building a new $22 million football practice facility, although the school has reported that donations are covering almost all of that cost.

Arkansas State, which tallied $29 million in total revenue in 2015, with 48 percent coming from student fees, university support and state funding, has added facilities, coaching staff and amenities, but athletic director Terry Mohajir said it’s not because the school is trying to keep up with its Power Five neighbors.

“We’re just trying to be the best that we can possibly be,” said Mohajir, whose school was a contender to be added to the Big 12. “Every day, we’re trying to increase everything we have.”

Arkansas State has had to replace its head football coach four times since 2011, having lost three to higher-paying head coaching jobs at larger programs.

“The Group of Five are trying to put ourselves as much as we can on a level playing field,” Mohajir said. Unlike the Power Five schools who receive multimillions annually in TV rights, “we don’t start out with a $30 million check in our pocket without having to raise one dollar. That’s a huge bonus … We don’t have that type of revenue, and we have to raise the money or the universities have to subsidize it.”

Mohajir said the state of Arkansas caps how much money the university can give athletics, and he’s not interested in increasing student fees, so the program has been working hard to earn private money through donations, licensing, royalties and ticket sales. The school has seen ticket sales increase by almost 40 percent since 2008, and contributions topped more than $5 million in 2014-15. Mohajir defends the program’s reliance on university and student fee support, because he said athletics brings students and extra tuition money to campus and makes the school more widely known outside Arkansas.

“We basically are the marketing arm of the university,” he said. “We recruit students to everybody’s college. We recruit students to be in the business school and fine arts … The ancillary revenue that you receive for a strong athletic program far outweighs the money the university spends – academic pride, student recruitment, recruiting the best talent and people in your state, and economic development in the community.”

Zimbalist said that is perhaps true for a handful of schools — some universities have seen a spike in enrollment after a team reaches the Final Four or achieves some other athletic milestone or major upset – but Zimbalist said there is no evidence across the board that a strong athletic program consistently attracts more high school students and increases the number of applicants.

Vedder, with the Center for College Affordability and Productivity, said there has been some correlation in Division I schools between athletic success and academic excellence, but it comes at a great cost. “If you took the $25 million in subsidies you gave for athletics and in turn used that money to increase instructional spending, you can get the same sort of instructional gains,” he said.

Vedder said there are also plenty of schools that have poured money into achieving athletic success that are still ranked low academically. He cited Boise State, which ranked 612 out of 660 schools in Forbes magazine’s America’s Top Colleges rankings, which Vedder and his colleagues compiled. Since 2008, Boise State increased its student fee and direct university support for athletics by a third to about $10 million, and its football team has finished in the top 25 six times. It was among those programs lobbying to get picked up by the Big 12.

According to the Outside the Lines analysis, among 13 public schools reported last month to have been vying to get into the Big 12, about 42 percent of their revenue on average came from student fees and outside subsidies in 2014-15. On average since 2008, they’ve spent 46 percent more on athletes’ tuition and expenses, and 57 percent more on coaching salaries.

One of those schools, the University of Houston, spent $26 million to support athletics in 2014-15, accounting for nearly 60 percent of the athletic department’s revenue. The Houston Chronicle, citing an email it received from an open records request, noted that UH chancellor Renu Khator wrote a professor in 2014 that if UH does not get into a major conference, “it will be difficult for us to sustain” what the school is spending on sports. The desire to make it into a Power Five conference is driven by many factors, but TV rights revenue is a major one. Last year, TV partners, including ESPN, paid the Power Five conferences nearly $1.4 billion. This summer, the Big 10 finalized a media rights deal with Fox, ESPN and CBS that will earn it on average about $440 million annually for six years.

Knight Commission executive director Amy Perko said schools need to be more transparent about their true costs. She said her commission has proposed several cost-cutting ideas, including shortening seasons or reducing games, putting a cap on the number of non-coaching personnel, limiting the number of sports required in Division I, and letting non-football sports compete with schools that are more aligned geographically to reduce travel time, scheduling and financial burdens.

Arkansas State’s Mohajir said he supports the idea of realigning the Group of Five conferences to be more geographically matched which would cut down on team travel costs, generate more regional rivalries and increase ticket sales.

But Zimbalist said the changes need to be more drastic and are likely to draw increased intervention by state governments and even Congress, where legislators have expressed interest in findings ways to rein in college sports spending.

“The system is being challenged, and it’s very much up in the air,” Zimbalist said. “There’s growing recognition that the current business model is not working out.”