Adrian Peterson doesn’t want redemption for whipping his child with a tree branch, but Sports Illustrated is delivering it to him anyway. Greg Bishop’s profile of the running back, published Tuesday, doesn’t hand out the redemption directly—it can’t, because Peterson is fine with what he did to his child— so instead it doles it out by implication. Here’s A.P. visiting a child dying of cancer; here’s A.P. being nice to his own son; here’s A.P. giving a motivational pep talk to one of his teammates. Tough guy to not like, right?

Despite explicitly disavowing the usual jock-redemption narrative, this story manages to hit all the marks in the standard player forgiveness profile, even as its subject insists he did nothing wrong. One of the greatest running backs in recent history doesn’t want your forgiveness, but SI, perhaps out of habit, tradition, or pure muscle memory, can’t help but make the case for it anyway.

The thin thread on which this case hangs is A.P.’s word that he no longer hits his children. Good news, certainly, but nothing that makes it any less strange to present the fallout from his child-abuse case as essentially another challenge among the many he’s overcome on the way to his touchdowns and rushing records. One of the many problems with this is that it centers the story on the effects things have on Peterson, rather than the effects he has on others. This reaches a ludicrous apotheosis in the presentation of the four-year-old A.P. fan Skyler Elfering’s death from a cancer that develops in immature nerve cells as a spur for Peterson to realize what it all means.

“Peterson is again reminded of the fragility of fatherhood, of life,” writes Bishop. “His son, the one from the abuse case, continues to visit him. ‘Their relationship,’ Ashley says, ‘that’s what matters.’”

There is a thoughtful profile to be done of Peterson that presents him as a spoke on a wheel, rather than its hub. It would clearly describe him as unapologetic, discuss how he learned to hit his children by growing up in a home and a community that still condone the practice, and closely examine how family violence gets passed down from generation to generation precisely because of the logic Peterson uses: My parents did it to me, and look how good I turned out.

This is not quite that, and every time Bishop gets near it, he layers on the schmaltz and suggests that Peterson has used his unfortunate difficulties as an opportunity to become a better person. (The kicker? One of A.P.’s sons saying, “Hi, Dad.”) Conveniently set in the middle, where it’s easiest for readers to miss it, are some of the details of what Peterson actually did.

Let’s start with this: Records show Peterson knew what he did, and it was more than one or two whacks on the butt. Peterson the told police that his son pushed another kid off a motorbike video game, and that this was the punishment. The beating, Nick Wright at CBS Houston reported, “allegedly resulted in numerous injuries to the child, including cuts and bruises to the child’s back, buttocks, ankles, legs and scrotum, along with defensive wounds to the child’s hands.”

The boy, according to the reports, said, “Daddy Peterson hit me on my face.”

The child also expressed worry that Peterson would punch him in the face if the child reported the incident to authorities. He also said that he had been hit by a belt and that “there are a lot of belts in Daddy’s closet.” He added that Peterson put leaves in his mouth when he was being hit with the switch while his pants were down. The child told his mother that Peterson “likes belts and switches” and “has a whooping room.”

http://deadspin.com/report-adrian-…

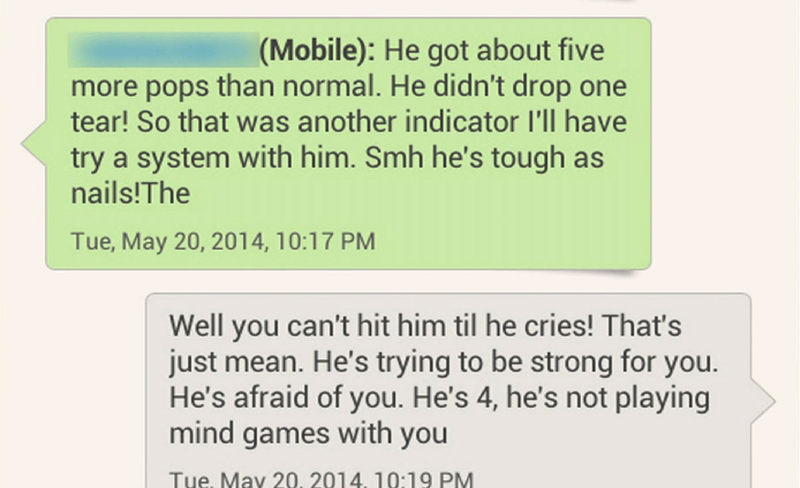

According to a leaked police report, Peterson texted the boy’s mother, “Got him in nuts once I noticed. But I felt so bad, n I’m all tearing that butt up when needed! I start putting them in timeout. N save the whooping for needed memories!” Here’s another text message exchange, published by CBS Minnesota, between Peterson and the boy’s mother.

This, via TMZ, is what “about five more pops than normal” looks like

These photos were left out of the SI story.

A detailed piece by USA Today last year discussed how Peterson grew up in Palestine, Texas, a tiny town where corporal punishment was doled out by parents, by the high school, even by a football coach. One of Peterson’s uncles recalled when a teacher said A.P. might need medication for ADD, and the boy’s father responded by saying, “It’s not something that a little whipping can’t take care of.” Like so much family violence, this was learned.

Reams of research show that beating children teaches them nothing. It stops behaviors in the short term, but as Elizabeth Gershoff, a University of Texas Austin professor who has been studying corporal punishment for more than 15 years, told CNN, “Most of us will stop what we’re doing if somebody hits us, but that doesn’t mean we’ve learned why somebody hit us, or what we should be doing instead, which is the real motive behind discipline.”

And yet, away from science and at home with a screaming toddler, things can be different. Anyone who has tried and failed to discipline a misbehaving child recognizes the urge, the sense that if words won’t work maybe spanking will. Many of us tell ourselves what A.P. did: It’s not that bad, because my dad hit me and I turned out great. Gershoff points out that the flip side of “Hey, I turned out okay” is that you might have turned out at least as okay, and less bruised, without the beatings. That can be hard to remember in the heat of another toddler tantrum.

None of this absolves Peterson, though—abusers don’t necessarily act out of malicious cruelty—and probably no one would be much interested in any of it if he wasn’t averaging 4.5 yards per attempt this season. The truth is that if a lesser player had done what A.P. did he would have been cut, like Ray Rice, and never given a second thought. He was charged with felony injury to a child in Texas, a state that allows corporal punishment even in school. He pleaded no contest to a lesser charge, misdemeanor charge of reckless assault. Peterson didn’t cross some fuzzy, liberal, blue-state line. He crossed the line in Texas.

Somehow, most of this got glossed over in the SI profile. Instead, readers are left with the idea that “wide swaths of Americans don’t feel the way he does.”

What SI has delivered here is essentially service journalism; the service is making it easier for Vikings fans to root for A.P. without feeling bad about his felony child-abuse charge and lack of remorse. It makes sure to list all the struggles A.P. had to overcome, real struggles that he deserves credit for weathering, but which, taken together in this context, amount to a case for both the understanding Peterson says he wants and the forgiveness he says he doesn’t.

He prays on it!

Peterson told himself to let it all go, to pray. But it still bothers him. “I know in my heart there’s not many fathers better than me,” he says. “I’m that father that the kids run to. I’m the father they want to wrestle and play with.”

He backs off of his feelings on Cris Carter, once he realizes how it sounds for him to say that he wants to hit someone who displeases him.

“Cris Carter, he had so much to say,” Peterson says. “In that stage, if I would have seen Cris Carter, I probably would have slapped the taste out of his mouth.” Another pause, as if Peterson realizes how this sounds. “Because that was the mind frame I was in,” he says. “I wouldn’t have done it. But I wanted to.”

He insists that he doesn’t want you to be okay with him because he helped your fantasy team!

The season he had speaks to Peterson’s resiliency and football prowess, but not to his personal growth—and he’s careful not to confuse them. Peterson doesn’t want his on-field performance to factor in to his public forgiveness. He wants people to understand how he views what happened, the cultural divide that in his eyes led to his scorning. But, with a shrug, he agrees with Ashley, who says, “I feel like if he wasn’t having such a great season, the reaction wouldn’t be as positive.”

The strangest thing about locating an opportunity for personal improvement in Peterson’s many trials is that he’s made no attempt to hide that he isn’t a better man now than he once was. He made that very clear in this ESPN profile from August, and even in the SI piece the truth comes through. The reality is there are going to be people like Ben Roethlisberger and Greg Hardy and Adrian Peterson in the league as long as they can play, and that to a large part of the public that’s the only thing that matters about them. Adrian Peterson understands that; does SI?

Image via Getty