Boris Johnson sought to suspend Parliament to avoid the risk of MPs “frustrating or damaging” his Brexit plans, the Supreme Court has heard.

Lawyers for campaigners challenging the suspension said there was “strong evidence” the PM saw MPs “as an obstacle” and wanted to “silence” them.

But a government lawyer said the PM was “entitled” to suspend Parliament, and it was not a matter for the courts.

The judges are hearing two challenges relating to the five-week prorogation.

Lady Hale, President of the Court, stressed the landmark case would have no bearing on the timing of Brexit.

In her opening statement, the most senior judge in the UK said she and her 10 colleagues would endeavour to address the “serious and difficult questions of law” raised by the case, but would not determine “wider political questions” relating to the Brexit process.

- Updates as PM’s suspension of Parliament goes to court

- Could the Supreme Court overrule the government?

- Who is Gina Miller?

Mr Johnson maintains it was right and proper to terminate the last session of Parliament in order to pave the way for a Queen’s Speech on 14 October, in which his new government will outline its legislative plans for the year ahead.

He insisted the move had nothing to do with Brexit and his “do or die” pledge to take the UK out of the EU on 31 October, if necessary without a deal.

But last week, Edinburgh’s Court of Session found in favour of a cross-party group of politicians challenging the PM’s move, ruling the shutdown was unlawful and “of no effect”.

Scotland’s highest civil court found Mr Johnson’s actions were motivated by the “improper purpose of stymieing Parliament”, and he had effectively misled the Queen in the sovereign’s exercise of prerogative powers.

SNP MP Joanna Cherry – who was also one of the lawyers on the case – told the BBC she was “cautiously optimistic” the Supreme Court would uphold the Scottish court’s ruling.

But, she added: “If they don’t, then they will be accepting that it’s possible under the British constitution for the prime minister of a minority government to shut down Parliament if it is getting in his way, and that just can’t be right.”

The Advocate General for Scotland, Lord Keen QC, is now appealing against the ruling, but told the Supreme Court that if it was upheld, the prime minister would take “all necessary steps” to comply.

However, after being pushed by the judges, he said he would not comment on whether Mr Johnson might subsequently try to prorogue Parliament again.

Lord Keen said previous prorogations of Parliament had “clearly been employed” when governments wanted to “pursue a particular political objective”, adding: “They are entitled to do so.”

He added that even if an action like this was seen as “improper”, the decision would still stay within Parliament, not the courts, and it would be up to MPs to pass new laws to change that.

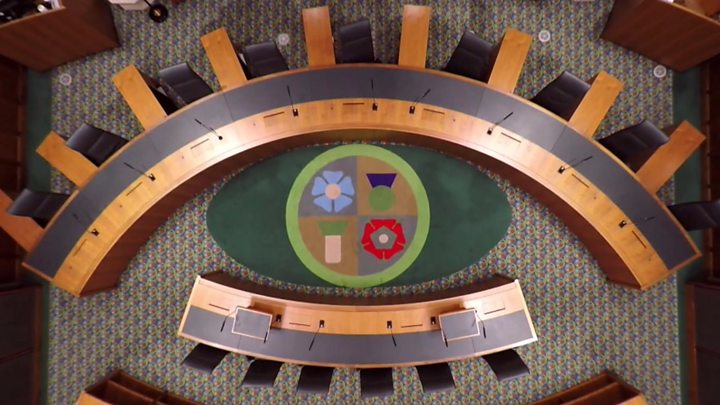

Image copyright

PA Media

Top row (from left): Lord Sales, Lady Arden, Lady Black, Lord Kerr, Lord Hodge, Lady Hale. Second row (from left): Lord Kitchin, Lord Lloyd-Jones, Lord Carnwath, Lord Wilson, Lord Reed

In a separate case earlier this month, London’s High Court rejected a challenge brought by businesswoman and campaigner Gina Miller, ruling that the suspension of Parliament was a “purely political” move and was therefore “not a matter for the courts”.

Appealing against that ruling in the same hearing on Tuesday, Lord Pannick – the crossbench peer and QC representing Ms Miller – told the Supreme Court he had “no quarrel” with a prime minister’s right to prorogue Parliament in order to present a Queen’s Speech.

However, he said the “exceptional length” of this suspension was “strong evidence the prime minister’s motive was to silence Parliament because he sees Parliament as an obstacle”.

The facts, he said, showed the PM had advised the Queen to suspend Parliament for five weeks “because he wishes to avoid what he saw as the risk that Parliament, during that period, would take action to frustrate or damage the policies of his government”.

Downing Street has refused to speculate on how the government might respond should they lose this court case.

Pressed this morning, the Justice Secretary, Robert Buckland, declined to say whether Parliament would be recalled, or indeed whether the prime minister might seek to suspend Parliament for a second time.

Mr Buckland said any decision would hinge on the precise wording of the court judgement.

Nevertheless, defeat would be a significant blow.

It would be the first time in modern history that a prime minister had been judged to have misled Parliament.

And if MPs were recalled, Mr Johnson would almost certainly face contempt of Parliament proceedings, accusations that he’d lied to the Queen, and pressure to reveal more details about his negotiating strategy and his planning for no deal.

Defeat in the Supreme Court would also make it much harder for the prime minister to defy MPs for a second time as he has threatened to do over their bill to block a no-deal Brexit.

Inviting the court to take a negative view of what he said was the PM’s failure to provide a witness statement explaining the basis of his actions, Lord Pannick said the court had a “common law duty” to intervene if the executive had used its powers improperly.

He said the effect of the suspension was to take Parliament “out of the game” at a pivotal moment in the UK’s history.

“The basic principle is that Parliament is supreme. The executive is answerable to Parliament.”

Image copyright

Getty Images

Gina Miller is appealing against an earlier ruling which found in favour of the government

Image copyright

Getty Images

The court case is expected to last three days

Lord Pannick said he disagreed with the High Court’s judgement that the issue was outside the scope of the courts.

“The answer is either yes, or it is no, but it is an issue of law, and the rule of law demands the court answers it and not say ‘it is not for us and it is for the discretion of the prime minister.’

“The prime minister cannot have a discretion over the breadth of powers he enjoys.”

It is only the second time that 11 justices will sit in a Supreme Court case – the first time this happened was in Ms Miller’s successful challenge as to whether the prime minister or Parliament should trigger Article 50 to start the process for leaving the EU.

They will determine whether prorogation is a matter for the courts, and if so, will go on to rule definitively on whether Mr Johnson’s true motive was to undermine MPs’ ability to legislate and respond to events as the country prepares to leave the EU.

Ms Miller is seeking a mandatory order which would effectively force the government to recall Parliament, BBC legal correspondent Clive Coleman said.

Opposition parties have called for Parliament to be recalled but at a cabinet meeting on Tuesday, Mr Johnson told ministers he was “confident” of the government’s arguments.

He told the BBC on Monday he had the “greatest respect for the judiciary”, and its independence was “one of the glories of the UK”.

Elsewhere on Tuesday, the prime minister has discussed Brexit in a phone call with German Chancellor Angela Merkel.

No 10 said afterwards: “The prime minister reiterated that the UK and the EU have agreed to accelerate efforts to reach a deal without the backstop which the UK Parliament could support, and that we would work with energy and determination to achieve this ahead of Brexit on 31 October.”