When he announced his reasons for not standing during the “Star-Spangled Banner,” San Francisco 49ers quarterback, Colin Kaepernick entered a decades-old debate over the song’s straddling of politics and sport.

A number of teams and individual players have dropped the anthem, or refused to acknowledge it, since it became part of gameday routines in the early half of the 1900s. In just about every case, the moves sparked public backlash — and, in the end, tradition won.

The practice dates at least back to the Civil War era, when the “Star-Spangled Banner” — written a half-century earlier — first became part of athletic events.

The first documented example was in May 1862, when Brooklyn inaugurated its first professional baseball field. The “Star-Spangled Banner” was played during a pregame ceremony, and again “at intervals throughout the contest,” the Brooklyn Daily Eagle reported.

From NBC Sports: The Anthem

In the decades that followed, the song resurfaced at baseball and college football games, usually during times of war and social upheaval. The trend continued after Congress made the song the national anthem in 1931, and through World War II, when patriotic fervor, along with the development of modern public address systems, made the song part of the everyday routine, Ferris said.

By the 1970s, television and big-money sports turned the pre-game national anthem into an event unto itself, with popular musicians performing it to huge crowds, according to Ferris.

But as the song became standard, it also piqued on-field dissent. Some thought the repeated playing cheapened it, while others saw it as a stage to protest American racism and foreign policies.

Related: Colin Kaepernick’s Protest is Part of Long Sports Tradition

Others simply couldn’t be bothered to pay attention.

In 1970, a high school football player in Illinois named Forrest Byram refused to take off his helmet during the “Star-Spangled Banner” and was suspended. He quit the team.

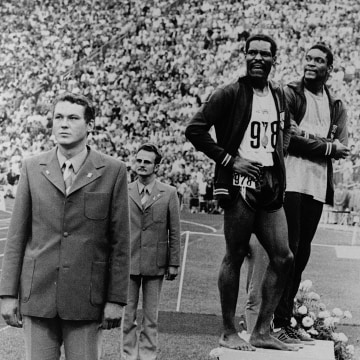

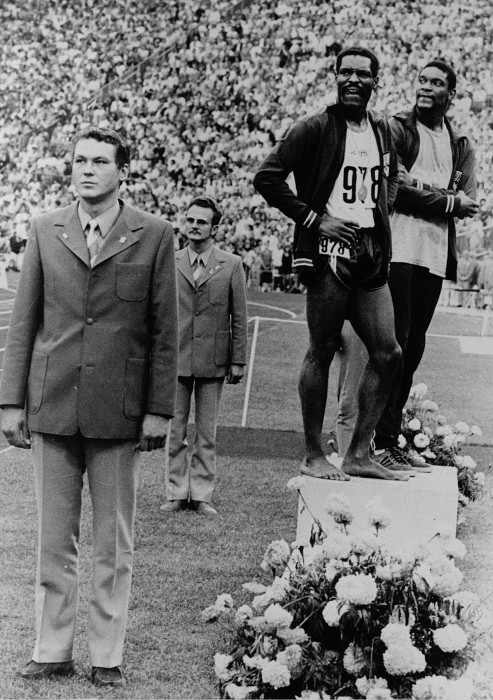

Two years later, at the Olympics in Munich, American sprinters Wayne Collett and Vince Matthews chatted casually during the playing of the U.S. national anthem. They were banned from the games.

A few months later, members of the Eastern Michigan University track team warmed up as the song was played before a meet, and were disqualified. Soon after, New York track officials dropped the “Star-Spangled Banner” from one of its most prestigious events, questioning the song’s relevance to sports. They quickly reversed course.

Other teams have tinkered with the national anthem, dropping it from all but special events, but have caved to public complaint.

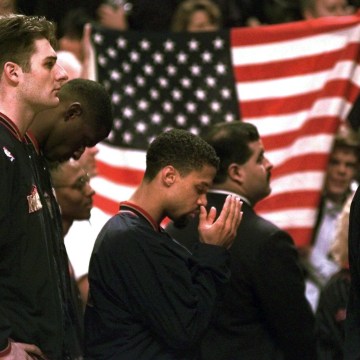

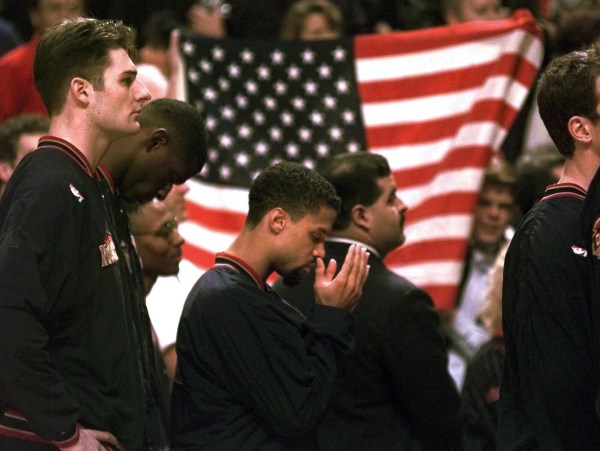

In 1996, rising-star Denver Nuggets point guard Mahmoud Abdul-Rauf — a recent convert to Islam formerly known as Chris Jackson — stopped standing for the national anthem, an act of defiance that wasn’t even noticed publicly for months.

When it was finally noticed, the move sparked public outrage and drew a suspension from the NBA, and Abdul-Rauf ultimately agreed to a comprise in which he prayed during the song instead. He was traded to the Sacramento Kings when the season was over and was out of the NBA by 2001, although his career continued internationally until 2011.

In 2003, Toni Smith, captain of the Manhattanville College women’s basketball team, began turning her back during the song to protest American inequalities and the coming war in Iraq. Her quiet protest drew attention only after a military veteran confronted her with a flag, and she sparked a national debate over free speech and patriotism.

Given this history, it only makes sense that Kaepernick has made his stand, Ferris said.

“The symbols of the country are always going to elicit patriotic and anti-patriotic feelings,” he said. “I just hope people will reflect and think about it instead of shouting at each other.”