1) Hussain bows out with match-winning hundred

The decision had already been made when Nasser Hussain went out for his final Test innings. An international career that spanned 14 years had seen him become perhaps the pivotal figure in the last few decades of English cricket. It was Hussain’s brilliant captaincy that had pulled England up from the nadir of being ranked last in the world and laid the groundwork for Michael Vaughan, the 2005 Ashes and all that. Vaughan got the glory, but he had Steve Harmison, Andrew Flintoff, Marcus Trescothick and Andrew Strauss at their peaks: Hussain’s first Test as captain featured Aftab Habib and Alan Mullally.

Hussain deserved to go out on top. The night before the final day of the first Test against New Zealand in 2004 Hussain, who had given up the captaincy the previous year, told the coach, Duncan Fletcher, that he was done, that the next day would be his last. Strauss was making his debut, had scored a century in the first innings and Hussain knew that he was the future. Hampering his progress would be irresponsible.

Still, he quite literally did that in the second innings, running Strauss out when he was on 83. “God, I can’t go now,” thought Hussain, thinking that the public would never forgive him if his last act was to prevent Strauss becoming the first Englishman to score two centuries on debut. He had to do something to make up for it, which he did with a flourish. Hussain’s last three shots all went to the boundary: the second brought up his century, the third won the Test.

“It was like someone upstairs saying, ‘You are doing the right thing and this is your reward,’” Hussain wrote in his autobiography. “As I walked off with Thorpey to the acclaim of Lord’s, my team-mates came down to congratulate me and the MCC members in the Long Room patted me on the back as I walked through to get the to dressing room. It was the most amazing time of my career, and it confirmed my decision for me.”

2) Double joy for El Guerrouj at the last

This Joy of Six is not necessarily designed for careers that ended happily, or even perhaps end on that athlete’s terms. Rather it is to provide a few examples of sportspeople whose last act was one of glory, who didn’t see their career drift away into ever diminishing returns.

Hicham El Guerrouj did not run straight off the track and into his dotage, medals flapping around his neck. There was in fact a two-year lag between his final race and retirement, two years in which he tried to compete but was scuppered by an increasingly debilitating series of injuries. A virus prevented his participation in the 2005 World Championships, a back problem in 2006.

But that final race was at the 2004 Olympics, as El Guerrouj became the first man in 80 years to complete the 1500m and 5,000m double. If glory is contained in the winning of close contests, then this was among the greatest feats of all time: El Guerrouj won the 1500m final by a yard or so, just edging out Bernard Lagat, while four days later he prevailed in an even closer race, hammering down the final straight to duck ahead of the world record-holder Kenenisa Bekele in the 5,000m. The glory was perhaps emphasised by his previous Olympic appearances: in 1996 he fell on the final lap of the 1500m final, and in 2000 he was beaten by Noah Ngeny, who at one time was El Guerrouj’s pacemakter.

In the following two years he tried to come back, but at some point in 2006 a peace seemed to descend on him. “I took the decision to retire because I suddenly began to sleep well three weeks ago,” he said. “Now it is done, I am relieved.”

3) Bartoli’s slow journey to the pinnacle

This is cheating slightly. The 2013 Wimbledon final was not actually Marion Bartoli’s final ever tennis match. That came 40 days later, a second-round loss to Simona Halep in Cincinnati, and a week before that she dropped out of the Rogers Cup in Toronto, forfeiting a game against Magdalena Rybarikova after firstly running out of rackets (Rybarikova leant her one) then suffering an abdominal injury.

But, if you like, Wimbledon was Bartoli’s last match in spirit. It was the final swing at glory, the sort of thing you might see in a two-star Channel 5 afternoon film about an ageing star with one more shot at the big time. “That was probably the last little bit of something that was left inside me,” said Bartoli when she bowed out in Cincinnati.

Bartoli was 28 in 2013 and had always been, not exactly a journeywoman, but a player on the fringes of the big time. Someone familiar with the top ten, but who never got higher than seventh in the rankings, and had played in 46 Grand Slams before Wimbledon 2013.

In the run-up to the tournament, Bartoli was in wretched form. In previous months she had suffered three first-round defeats, was absolutely destroyed by Francesca Schiavone at Roland Garros, had to depart a couple of times due to injury and lost one to the world No88 Camila Giorgi. “Bartoli did not so much fly under the radar as go subterranean,” wrote Kevin Mitchell of this parish. Bartoli was scheduled to face the third seed, Maria Sharapova, in the fourth round, but when the Russian was beaten by the qualifier Michelle Larcher de Brito, the draw opened up for Bartoli. Remarkably, the 15th seed Bartoli didn’t have to face anyone seeded higher than her in the whole run. She didn’t drop a set on her way to the title, and arguably the trickiest moment of her tournament was having to deal with John Inverdale’s insidious sexism.

Bartoli faced Sabine Lisicki, vanquisher of Serena Williams earlier in the tournament, in the final, but it was barely a contest. Bartoli outclassed her opponent to win her first Grand Slam at the 47th attempt – no one had played in more before winning their maiden big one. But after that her body seemed to give in: myriad injuries, not least that abdominal problem that did for her in Toronto, made it not worth the effort anymore. But she had reached the pinnacle, so it barely mattered: she recognised that she was unlikely to top that, and strode into retirement.

“You know, everyone will remember my Wimbledon title,” she said in Cincinnati. “No-one will remember the last match I played here.” Damn right.

4) Cantona quits with ‘nothing more to prove’

The last time Eric Cantona played professional football was on 11 May 11 1997. It was a nondescript 2-0 win over West Ham United, at the end of a season in which United completed plenty of nondescript wins on their way to the title.

That season Cantona had showed flashes of inspiration: it was a few months earlier he produced that magnificent chip against Sunderland, slowly turning around in celebration as if drawing attention to a great work. Which he was. But he also frequently looked listless, slightly disinterested, even a little bulkier than before. That season Alex Ferguson conceded that Cantona was merely part of, rather than key to, United’s success. He was, unquestionably, past his peak. So he stopped. It was as if this most pure of footballers didn’t want to sully the game with anything less than his best.

Cantona had made his decision well before the end of the season. He told Ferguson the day after a defeat to Borussia Dortmund in the Champions League, and despite his manager’s best efforts, encouraging him to take a week to think about things and discuss it with his father, Cantona would not be budged.

It was eight days after that final game that the announcement came, in the middle of a spring Sunday afternoon via a short statement by the chairman, Martin Edwards. Cantona was on holiday, well away from the shock he had caused in Manchester, slipping away quietly and, we are contractually obliged to say, enigmatically. Perfectly, in other words.

“I have nothing to prove,” he said in his first interview after retirement, “and I have no duty to show who I am to the people whom I find interesting. To the others – I have nothing to say.”

5) Marciano preserves perfect legacy against Moore

Name a boxer. Muhammed Ali, George Foreman, Lennox Lewis, Roberto Duran, Sugar Ray Leonard, Jack Johnson – they all lost. They all experienced the chastening stomach-sink of defeat, the greatest of respective generations at some point caught on a bad day, caught with a lucky punch, or perhaps just hung on too long.

That last bit is usually what does for boxing greats. There is something about the sport that persuades even the finest to keep going long after it is sensible, or dignified, or safe. Floyd Mayweather seems set on retirement (from boxing, at least), and Lewis has thus far managed to resist the urge to return, but he’s the exception to the rule, and even he lost a couple of times.

Rocky Marciano though, he remains the only world heavyweight champion to go a whole career without losing a fight. His record of 49-0 with 43 knockouts is fairly remarkable, to the point that it didn’t matter a great deal if the circumstances of his final fight were especially dramatic: the achievement in that last bout, against Archie Moore in 1955, was retaining that unbeaten record. Marciano was on the canvas in the fourth round of that fight, but recovered to knock his opponent out in the ninth.

Marciano actually announced his retirement some seven months after that fight, problems with his back and with his manager providing some reasons, but ultimately it was his legacy. “I don’t want to be remembered as a beaten champion,” he said.

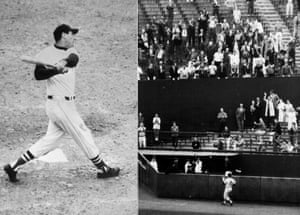

6) Williams defies his public in triumphant sign-off

Ted Williams is regarded by some as the greatest hitter baseball has ever seen. He was chosen for the All-Star team 19 times, quite a feat given that he missed five full years thanks to a couple of wars, where he served in the navy and US Marine Corps. He was the last player to average .400 in a single season, hitting .406 in 1951: for those unfamiliar, a solid average is .300, and the man currently regarded as the best in the sport, Mike Trout, has never managed more than .326 in a season. He spent his entire career with the Boston Red Sox, and was their shining light in barren years, when they lurched from romantic failure to just plain failure.

Despite this, Williams always had a “tricky” relationship with Boston, Red Sox fans and the local media. “I don’t like the town, I don’t like the people and the newspaper men have been on my back all year,” he once said, and more than once spat at spectators in Fenway Park. After some fans jeered a couple of fielding mistakes in 1940, he resolved never to “tip his cap” – the universally recognised way of acknowledging the crowd – ever again.

By the late 1950s, Williams was still going strong: aged 40 in 1958, he led the American League in batting averages, but in 1960 he decided to retire. His final game at home was against the Baltimore Orioles, and in his final plate appearance, Williams hit a soaring home run.

“It was in the books while it was still in the sky,” wrote John Updike in a magnificent article for the New Yorker. Williams, true to form, put his head down and ran around the bases, then straight into the home dugout, cap remaining firmly untipped, acclaim ignored.

“Though we thumped, wept, and chanted ‘We want Ted’ for minutes after he hid in the dugout, he did not come back,” wrote Updike. “Our noise for some seconds passed beyond excitement into a kind of immense open anguish, a wailing, a cry to be saved. But immortality is nontransferable. The papers said that the other players, and even the umpires on the field, begged him to come out and acknowledge us in some way, but he never had and did not now. Gods do not answer letters.”

When it was the Red Sox’s turn to field, the manager, “Pinky” Higgins, allowed Williams to take his position, then immediately replaced him, so that he could have one final curtain call. But Williams again put his head down and ran into the dugout, ignoring the yells of acclaim from the stands. The Red Sox were due to close their season with three games against the New York Yankees, but Williams decided not to make the trip. His final act as a baseball player was to hit a home run, then ignore the fickle crowd. For a man whose career in Boston was defined by his brilliance, stubbornness and antagonism towards those who watched him every day, it seemed rather appropriate.