1) Diego Maradona faces six fiercely focused Belgians

Camp Nou in Barcelona at the 1982 World Cup in Spain. With the ball at his feet, his famous left foot caressing it as he ponders his next move, Diego Maradona balances on the toes of his right foot surveying the scene ahead of him. Front and centre stands Belgium midfielder Franky Vercauteren with five of his team-mates fanning out in formation behind him. The visual suggestion is clear: such is the reputation for skill of the young genius on the ball that it might take up to six men to stop him. The essence of Maradona captured in one frame, there is no little irony in the fact that all is not quite what it seems.

While Steve Powell’s wonderful image suggests the Belgians were so stricken with panic at the sight of Maradona on the ball they assigned a squadron of players to hunt him down in formation, the truth is disappointingly prosaic. The Belgians were in such close proximity to each other because they had just been standing shoulder to shoulder in a defensive wall formed several metres outside their own penalty area to obstruct an Ossie Ardiles free-kick. As the Spurs star played the ball short, rolling it to Maradona who was standing about 10 metres away, it was hastily dismantled. Located behind the Argentinian midfielder, high up in the gods, it was at this exact moment Powell captured his famous image. Rather than take on and beat the opposition players in front of him, as the photo suggests Maradona was about to do, he chose instead to attempt to pick out a team-mate on the far side of the penalty area, only to see his chipped pass headed clear by Luc Millecamps.

“There was an awful lot of luck involved in getting it, but lots of memorable photos are like that,” he later told Jonny Weeks, from the Guardian’s picture desk, who consulted the photographer for a fascinating essay on the image. “You just have to concentrate and be ready for the opportunities. Ultimately it’s not about the composition; it’s not about art; it’s not about that particular game; it transcends that. It’s about communication. It communicates the power of Maradona and the fear he instilled. It’s about this one man and the relationship he had with opposing players.”

What Powell’s image does not reveal is that Belgium won that particular match 1-0, while Maradona would go on to be the subject of another even more iconic World Cup image captured during a match against England in Mexico four years later.

2) Brandi Chastain celebrates winning the World Cup final

“It was fate that brought us together,” said Brandi Chastain of Sports Illustrated snapper Robert Beck, whose photo of the USA footballer’s famous celebration of the decisive spot-kick that won the host nation the 1999 Women’s World Cup final would go on to become the defining image of the tournament. She was a last-minute choice of penalty-taker, while he had come within a hair’s breadth of being moved on from his spot behind the goal into which she fired the final penalty of the shoot-out in which the USA beat China following a stalemate low on drama but high in tension, in front of over 90,000 supporters at Pasadena’s Rose Bowl. Such are the margins when it comes to capturing a moment for pictorial posterity to celebrate a tournament that had captured the heart of the American nation.

“Momentary insanity, nothing more nothing less,” said Chastain, upon being asked what prompted her to celebrate her tournament-winning penalty by taking the unusual step – for a female footballer at least – of removing her shirt to reveal a black sports bra and slide to her knees, her face a picture of undiluted rapture as her team-mates sprint towards her and she clutches her sweat-sodden jersey in one of her raised and clenched fists. “I wasn’t thinking about anything. I thought: ‘This is the greatest moment of my life on the soccer field’.”

It was also the greatest moment of Beck’s life on the soccer field, not that he’d spent too much time on it previously. A specialist in taking action pictures of surfers, the photographer didn’t even understand the rules of football and had really only been sent to the final as Sports Illustrated’s third staffer, to take pictures of the good and the great in the crowd or anything else that happened to catch his eye. Located somewhere high in the stands as the game approached full-time, he asked the assistant tasked with helping him to lug his equipment around what would happen if the game ended in a draw. Upon being told of the possibility of a penalty shoot-out, the pair made their way to the tunnel before heading out on to the edge of the pitch at the end of extra-time. “Nobody paid attention to us,” Beck would later reveal.

With his two colleagues stationed at each corner flag in line with the goal into which the shoot-out would take place, Beck found a spot directly behind the goal alongside a fellow photographer, who was manhandled away by security officials. Upon being told he wasn’t allowed to be there either, Beck began packing up his equipment only to be told to stay put because the penalties were about to begin and any unnecessary movement behind the goal might distract those taking them. Beck had unwittingly secured himself exclusive rights to the best vantage point in the stadium.

A habitual right-footed penalty-taker who had an effort saved by China goalkeeper Gao Hong in a previous tournament, Chastain was the subject of much debate as the American coaching staff selected their first five penalty takers. Before the game, Tony DiCicco had had her practice taking them with her left foot, because he believed she was more accurate with it. DiCicco’s assistant, Lauren Gregg, believed she shouldn’t be among the five at all, as she’d had a middling year shooting from the spot and it would later emerge that Chastain was a last-minute addition to the quintet in place of her team-mate Julie Foudy, because her manager felt she would be better able to take the pressure.

While USA goalkeeper Briana Scurry turned away China’s third spot-kick in the shoot-out, Carla Overbeck, Joy Fawcett, Kristine Lilly and Mia Hamm all converted to leave their team one kick from World Cup glory. Chastain made the long lonely walk from the centre-circle, placed the ball on the spot and took a deep breath. Waiting for the referee’s whistle, she was completely oblivious to Beck sitting behind the goal with his index finger poised.

Beck’s photo of Chastain’s celebrating with her shirt off as the blurred forms of her ecstatic team-mates can be seen galloping to converge on her in the background went on to make the cover of Sports Illustrated, Newsweek and Time Magazine. “It was probably something that never should’ve happened because I was in the wrong place at the right time. I had a version that nobody else had because I was directly behind the net.”

Chastain would later be accused, rather harshly it must be said, of deliberately removing her shirt in a bid to make the moment of victory prompted by her winning penalty all about her, to the exclusion of her team-mates. It is an accusation she flatly denies. “What I explain to people is, imagine the moment you created as a kid in the playground many, many times – where you have the last shot and the clock is ticking down and the crowd goes wild,” she later said. “Maybe in the playground you jump up in the air or pump your fists. But to do this in real life: the emotion and the energy and the electricity and the crowd – it was insanity because I wasn’t really in control. It was just a spontaneous expression to a wonderful moment, but a moment that was a lifetime in building.”

3) Andrew Flintoff commiserates with Brett Lee

Having lost at Lord’s in the opening Test of the 2005 Ashes, England had just beaten Australia at Edgbaston in one of the most thrilling games of cricket ever played. With the hosts needing only one wicket and the tourists only four runs short of victory, Brett Lee and Michael Kasprowicz were at the crease while sizeable chunks of the population of both nations watched on tenterhooks. Showing a level of skill with bat in hand that ought to have been well beyond a man of his supposedly limited capabilities, Lee had defended his wicket heroically on the fourth day, adding runs at a steady pace and almost nicking victory with a wild biff towards the rope that would have won the Test for Australia but for the presence of an England fielder. With three runs required, Australia’s obdurate stand ended when Lee’s batting partner Kasprowicz was caught behind courtesy of an acrobatic tumbling catch from England wicketkeeper Geraint Jones.

Any doubts that the nature and moment of England’s nerve-shredding second Test victory were potentially series-defining were dispelled by the unbridled jubilation of the players’ celebrations. Scattering briefly to all corners like captive mice who’ve just been released at a crossroads, they eventually reconvened to engage in a well-earned orgy of back-slapping and self-congratulation. In acts of sportsmanship for which the bubbling cauldron of an Ashes Test is not renowned, Andrew Flintoff distanced himself from the celebrations to sympathise with the visibly shattered Lee in a photo opportunity seized upon by the Guardian’s eagle-eyed photographer Tom Jenkins.

The imagine of Flintoff hunkered down, one of his giant hands clasping the stricken Australian’s while the other rests on his shoulder is an image of sportsmanship at its finest, even if Flintoff did attempt to make light of his magnanimity in victory by telling anyone who asked what he’d been saying to Lee was: “It’s 1-1 now, you bastard!”

Moments previously, England seamer Steve Harmison had been the first to commiserate with Lee, adopting a similar pose to Flintoff, albeit one that wasn’t beamed around the world. “We tried everything with Brett and then I saw him on his knees,” said Flintoff, before steaming into Harmison with: “As a kid at Lancashire I was taught that you respect the opposition and you respect the umpires, then it’s time to celebrate. At Durham, Steve was also taught that, but what Steve wasn’t taught is how to work a camera. Steve actually shook Brett’s hand first, but he’s not very camera savvy. I went afterwards and then they took that photograph and it was beamed around.”

Flintoff has also joked that he can’t remember what he was saying to Lee at the time, although he did concede later that anything that came out of his mouth is unlikely to have been too profound. In truth, it doesn’t really matter what was said between the pair. This picture of their embrace tells us everything we need to know.

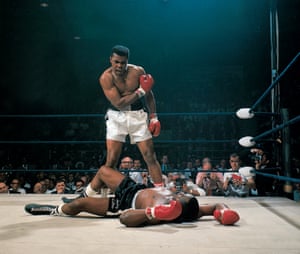

4) Muhammad Ali stands over Sonny Liston

First round. First minute. His upper lip curled back to reveal the white gum shield protecting a mouth sneering with contempt, Muhammad Ali stands over the prone body of Sonny Liston. Towering over his stricken opponent, apparently daring one of the most intimidating and skilled fighters in history to even try to get back to his feet with a contemptuous flick of the powerful right arm with which he’d just felled Liston in the opening round of their 1965 rematch at the Central Maine Youth Center in Lewiston. Taken by Sports Illustrated photographer Neil Leifer, it is arguably the most iconic image in the history of all sport and by his own admission, the man who took it was extremely fortunate to get it.

Aged only 22 at the time and a junior photographer with the magazine, Leifer had originally stationed himself on the opposite side of the ring near the judges’ table, but had been ordered to sling it by his more senior colleague Herb Scharfman, the bald gentleman with the black-rimmed spectacles who can be seen through Ali’s legs in Leifer’s photograph. Leifer lucked out in his new position, ending up in the perfect spot to capture the moment immediately after Liston hit the deck.

The challenger would groggily return to his feet at the second attempt, but the fight was all but over as a contest and was stopped soon afterwards. “If I were directing a movie and I could tell Ali where to knock him down and Sonny where to fall, they’re exactly where I would put them,” Leifer later said in an interview with the American writer Dave Mondy to mark the 50th anniversary of the bout.

Taken in colour and very similar to a less defined black and white photo taken by Associated Press lensman John Rooney, who was sitting to his left, this was one of three famous images captured by Leifer on the night. “I will never have a night like that ever,” he told Mondy. “I mean I’ve never had another one like that. The fight went two minutes and eight seconds and I got three great pictures.” Ali standing over Liston as seen from ringside remains the most memorable, famous and celebrated. Full of naked, raw aggression, it is the study of an almost perfectly beautiful physical specimen standing on the cusp of certain victory. Ali at the very peak of his powers, just as we should remember him.

5) Jos Verstappen’s pit inferno

No Formula One drivers or pit crew were harmed during the taking of this photograph. Well, not seriously harmed, which seems remarkable when you consider the size, heat and intensity of the shocking pit lane fireball that engulfed Jos Verstappen’s car during his first scheduled stop at the 1994 German Grand Prix at Hockenheim. A veteran driver for the Benetton-Ford team, the Dutchman had pulled into the pits, where his little pit crew army set about their individual tasks with their usual well-practised efficiency. Raised by the front and rear jacks, the wheels were replaced as the fuel hose was attached and its contents sent fizzing into the tank, a process which took fewer than two seconds.

In TV footage of the stop, Verstappen can be seen inching open the visor of his helmet with his left hand as the hose is detached from his car by one of the two refuellers. We see car, driver and several of the crew get liberally soaked by fuel that had somehow continued to gush from the hose and in the millisecond before it all goes up in flames after being ignited by the heat of the exhaust or brake pads, there is an almost comic moment as Verstappen appears to wave away his attendants in a gesture of extreme irritation. Then: woof … the inferno, engulfing the car and its driver and all those working around him. Only the flame retardant material of the garments being worn by all concerned, not to mention the lightning quick reaction of those grabbing the nearby fire extinguishers prevented grisly, agonising disaster.

Of all those involved, only Verstappen was hurt – quickly emerging from his car with minor facial burns, from where his visor had been open. An investigation later found the accident had been caused by an illegal fuel valve that Benetton were using that had no filter and therefore speeded up the refuelling process. “The key to photographic success is to be prepared and stay still,” said photographer Arthur Thill to the Times, after capturing some incredible shots of the pit lane blaze. Standing about 10 metres away from the car as it came to a standstill, Thill noticed the fuel splashing over the car and braced himself for whatever disaster was about to unfold. “Everyone else ran away in shock, but I knew what was coming, so I kept shooting,” he said. The outcome? Fourteen flaming frames of inferno Thill described as “the most spectacular set of my career”.

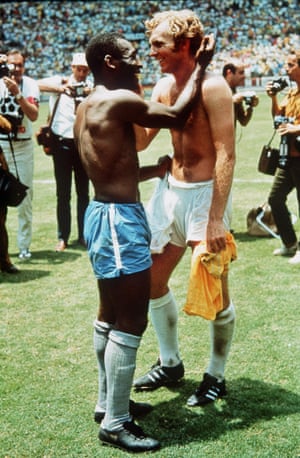

6) Bobby Moore and Pelé embrace

Described by Bobby Moore as his favourite photo of himself, this picture of the England captain and Pelé embracing after the 1970 World Cup group game between England and Brazil at the Estadio Jalisco, Guadalajara in Mexico has since become one of the most enduring images in football, if not all of sport. One of the more endearing qualities of this image is that it’s impossible to tell whose team had just won, but even though England had gone down 1-0 to a memorable 59th-minute Jairzinho strike, their captain looks fairly chipper after swapping shirts with Pelé in the wake of a match that produced two other historic moments: Gordon Banks’s incredible save from Pelé and that tackle on Jairzinho by Moore.

A study of sportsmanship and mutual respect between two of the game’s totemic figures, the photograph was taken by John Varley, a Leeds-based staffer with the Daily Mirror who, as part of his contract with the paper, had a sabbatical every four years timed to coincide with every World Cup from 1966-1982. More accustomed to covering the “proper news” of conflicts and natural disasters in his day job, Varley and reporter Alan Staniforth participated in the South American stage of the World Cup rally, but a breakdown outside Mexico City meant the photographer was forced to hitchhike to the opening ceremony.

Following the final whistle of this match in Guadalajara, Varley sauntered on to the pitch with several colleagues and loitered with intent near Moore in the hope that Pelé would approach him and a suitable photo opportunity would present itself. To his delight, the Brazilian duly obliged.

Pelé said upon hearing of Moore’s death in 1993: “He was my friend as well as the greatest defender I ever played against. The shirt he wore against me in that 1970 match is my prize possession. The world has lost one of its greatest football players and an honourable gentleman.”

As for Varley, aged 35 at the time of this photo, he died in 2010, aged 76, with a copy of this photo signed by Pelé reported to be among his own prized possessions.