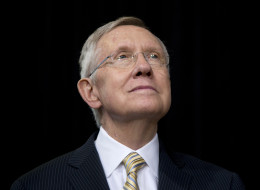

The Senator From Searchlight – Huffington Post

Harry Reid’s announcement that he will not stand for reelection to the Senate from Nevada in 2016 is a major loss for the climate movement — and yet another signal that the U.S. Senate is being transformed by today’s bifurcated, parliamentary politics into an institution almost unrecognizably different from its traditions.

But while Reid may be the last Senate traditionalist to serve as Majority Leader, he was first and foremost the product of his own history as a miner’s son who put himself through Georgetown Law School by working as a capitol police officer. Searchlight was a hardscrabble town; Reid had to hitchhike to high school, and his house had no indoor plumbing, even in prosperous postwar America. And Reid’s political future was forged in the boxing ring, where his high school coach was future Nevada Gov. Mike O’Callaghan, the mentor who later pulled Reid into the lieutenant governor’s race. His opponents and competitors often mistook Reid’s laconic, soft-spoken demeanor for weakness. They never saw his counterpunch coming.

But if you understood his values and his approach, there was no better partner in the political arena. Unlike most politicians, Reid knew how to be silent and when to cut to the chase. He respected political players who stood their ground firmly; the harshest thing I ever heard him say about a fellow senator was “He’s a nice, smart man, but he has no backbone whatsoever.” But he worked effectively with that senator for decades.

Early in Reid’s Senate career, I made an egregiously unfair attack on him for his strong defense of the mining industry against environmental reformers like myself. He made it clear that he didn’t mind the disagreement but that I had besmirched his motivation and forgotten that he was a miner’s son from Searchlight. I apologized, corrected the record, and promised that, in the future, I would judge him on his actions and not make assumptions.

When Richard Bryan, Reid’s Democratic fellow senator from Nevada, resigned in 2001, Reid took up Bryan’s long crusade to protect Nevada from becoming the U.S. nuclear industry’s dumping ground, standing — often almost alone — against efforts in the Senate to force the licensing of Yucca Mountain as a nuclear waste repository in spite of ample evidence that the selection of this site was based not on the merits but on Nevada’s small population and weak political clout, and that the site was geologically incapable of reliably storing waste for the lifetime of the risk. Since Yucca had been the major glue in the Sierra Club’s partnership with Bryan, I came into close working contact with Reid, and reliably, every two or three years, there would be a threat in Congress to overturn science and jam Yucca down Nevada’s throat. Las Vegas became a regular part of my political forays, and a partnership was born.

As Reid watched climate science take on increasing urgency after he became Majority Leader in 2005, one of his earliest policy initiatives was to state simply that he was opposed to coal-fired power plants in Nevada, and that he was convinced that the state would be better served by a clean-energy future. He was as good as his word. Thanks in large part to his tireless efforts, Nevada utilities abandoned their 2004 plans to construct five huge new coal plants in the state, shifted their focus to renewables, and by 2015 all the state’s legacy coal plants had either shut down or been given shuttering dates.

Reid didn’t just help get Nevada off coal; he poured his energy into building the state into a renewable-energy powerhouse, one that generates more clean energy per capita than any other state. In Las Vegas he began holding a series of clean-energy summits that brought renewable-energy advocates together to strategize and build their sector, and now that he has announced his retirement, clean energy is one of the top priorities Nevadans expect him to pursue during his last two years.

But his environmental record is not confined to energy. During the George W. Bush administration Reid was often the environmental movement’s man on issues ranging from clean air to water and public lands. He created Nevada’s first national park, Great Basin; fought for the protection of Lake Tahoe; made the restoration of Nevada’s two desert lakes, Pyramid and Walker, a personal passion; and added hundreds of thousands of acres to Nevada’s share of the national wilderness system.

Reid was a Senate traditionalist. Ironically, he was sadly forced to leave as part of his legacy the first significant changes in the powers of the Senate majority since the 1960s. Beginning with Sen. Bob Dole’s response to Bill Clinton’s 1992 victory, Senate Republicans converted the filibuster from an occasional Senate showstopper into a regular, debilitating and unprecedented tool used by the minority party to freeze virtually all legislative action. This was a revolutionary change, but it didn’t require changing the rules, just changing Minority Leader behavior. When Mitch McConnell took this practice to unprecedented levels after the election of Barack Obama, paralyzing the federal government, Reid first tried to reach a gentleman’s agreement with McConnell, against the arguments of younger senators who through that the Senate’s traditions had to yield to political reality. Finally, in November 2013 Reid led his Democratic majority to eliminate the filibuster for most presidential nominees — and did so using a parliamentary procedure that means that any future Majority Leader could eliminate the filibuster altogether if he or she chose to do so.

Reid’s climate, environmental and political legacy is thus an unexpected one — hardly predictable given his origins as a hard-rock miner’s son, or his instincts as a cautious Senate traditionalist. It’s hard to identify his most important victory. Was it that George W. Bush’s environmental legacy was less damaging than his wars? That Yucca Mountain spared the U.S. the economic and safety black swans that come with a nuclear revival? That America’s energy future shifted from Dick Cheney’s coalageddon to a clean-energy revolution? Or that we saw the beginning of a democratic, majoritarian U.S. Senate — even against Reid’s preferences?

Harry Reid fought the battles of his time; chose wars of necessity, not of choice; and fought them for the values he cherished. The Senate will be a lesser place once he is gone.