Image copyright

Spl

Coral reefs are threatened by the acidification of the oceans

Climate change is devastating our seas and frozen regions as never before, a major new United Nations report warns.

According to a UN panel of scientists, waters are rising, the ice is melting, and species are moving habitat due to human activities.

And the loss of permanently frozen lands threatens to unleash even more carbon, hastening the decline.

There is some guarded hope that the worst impacts can be avoided, with deep and immediate cuts to carbon emissions.

This is the third in a series of special reports that have been produced by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) over the past 12 months.

- Email your question about the IPCC report to haveyoursay@bbc.co.uk.

The scientists previously looked at how the world would cope if temperatures rose by 1.5C by the end of this century. They also reported on how the lands of the Earth would be affected by climate change.

However, this new study, looking at the impact of rising temperatures on our oceans and frozen regions, is perhaps the most worrying and depressing of the three.

- What is climate change?

- Global warming causing ocean ’emergency’

- Thunberg to leaders: ‘You’ve failed us on climate’

- Twelve years to save Earth? Make that 18 months…

So what have they found and how bad is it?

In a nutshell, the waters are getting warmer, the world’s ice is melting rapidly, and these have implications for almost every living thing on the planet.

“The blue planet is in serious danger right now, suffering many insults from many different directions and it’s our fault,” said Dr Jean-Pierre Gattuso, a co-ordinating lead author of the report.

Image copyright

SPL

Low-lying small island states will be badly hit by sea level rise

The scientists are “virtually certain” that the global ocean has now warmed without pause since 1970.

The waters have soaked up more than 90% of the extra heat generated by humans over the past decades, and the rate at which it has taken up this heat has doubled since 1993.

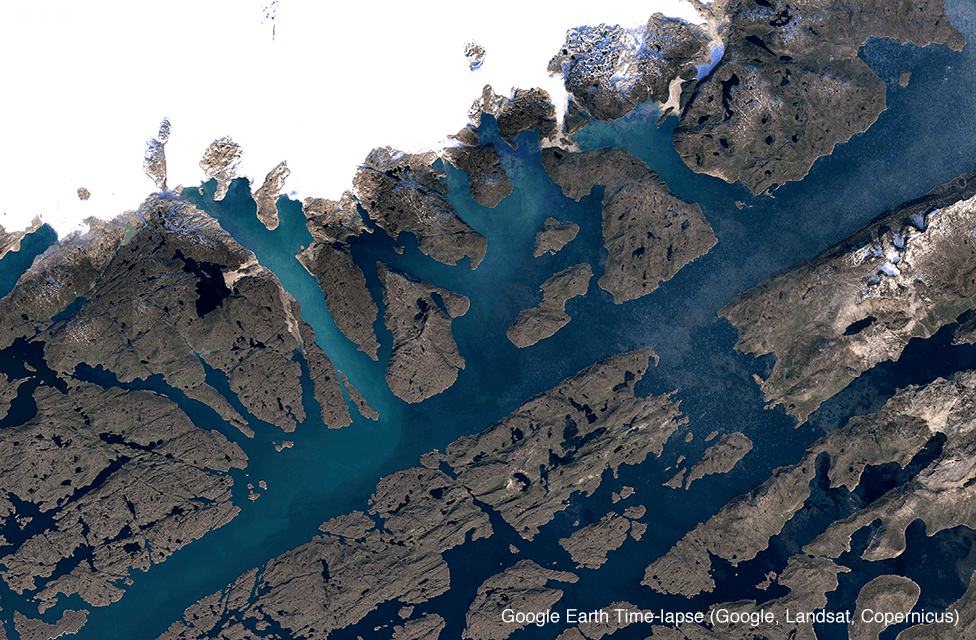

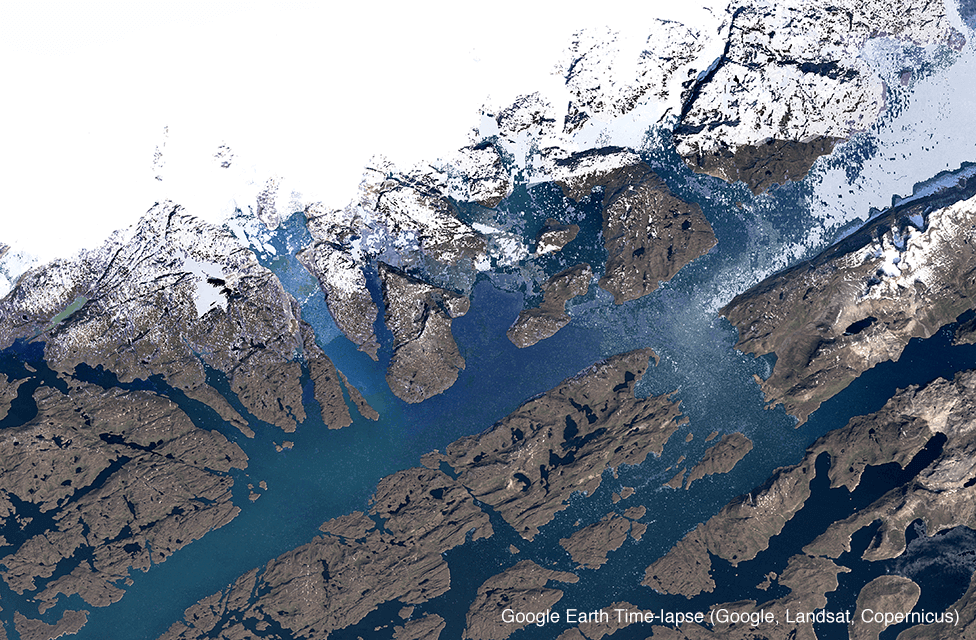

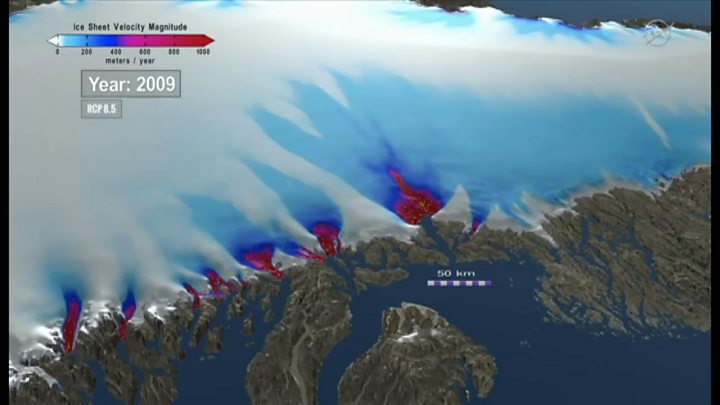

Where the seas were once rising mainly due to thermal expansion, the IPCC says this is now happening principally because of the melting of Greenland and Antarctica.

Thanks to warming, the loss of mass from the Antarctic ice sheet in the years between 2007 and 2016 tripled compared to the 10 years previously.

Greenland saw a doubling of mass loss over the same period. The report expects this to continue throughout the 21st Century and beyond.

For glaciers in areas like the tropical Andes, Central Europe and North Asia, the projections are that they will lose 80% of their ice by 2100 under a high carbon emissions scenario. This will have huge consequences for millions of people.

Image copyright

Science Photo Library

Glaciers around the world are losing their ice fast

What are the implications of all this melting ice?

All this extra water gushing down to the seas is driving up average ocean water levels around the world. That will continue over the decades to come.

This new report says that global average sea levels could increase by up to 1.1m by 2100, in the worst warming scenario. This is a rise of 10cm on previous IPCC projections because of the larger ice loss now happening in Antarctica.

“What surprised me the most is the fact that the highest projected sea level rise has been revised upwards and it is now 1.1 metres,” said Dr Jean-Pierre Gattuso, from the CNRS, France’s national science agency.

“This will have widespread consequences for low lying coasts where almost 700 million people live and it is worrying.”

Analysis by David Shukman – Science Editor, Hull

On the east coast of England, most of the city of Hull lies below the level of a typical high tide. The sea here can be both a source of wealth and a threat to life.

So the conclusions of the IPCC report have real meaning. A storm surge on a winter’s night six years ago found a weak link in a sea wall and flooded businesses and homes.

New defences were ordered and the construction teams are now at work along the shore. But the barriers cannot protect everyone. Computer simulations, developed by the University of Hull, show that if the level of the ocean is one metre higher than now the centre of the city ought to be fine but neighbouring areas will go under.

This highlights a painful question, faced in low-lying places the world over: which should be saved and which should be abandoned as the waters rise?

Sea level rise was once mainly due to thermal expansion of the oceans, but the melting of Greenland and Antarctica has now taken over as the principle driver

The report says clearly that some island states are likely to become uninhabitable beyond 2100.

The scientists also say that relocating people away from threatened communities is worth considering “if safe alternative localities are available”.

What will these changes mean for you?

One of the key messages is the way that the warming of the oceans and cryosphere (the icy bits on land) is part of a chain of poor outcomes that will affect millions of people well into the future.

Under higher emissions scenarios, even wealthy megacities such as New York or Shanghai and large tropical agricultural deltas such as the Mekong will face high or very high risks from sea level rise.

The report says that a world with severely increased levels of warm water will in turn give rise to big increases in nasty and dangerous weather events, such as surges from tropical cyclones.

“Extreme sea level events that are historically rare (once per century in the recent past) are projected to occur frequently (at least once per year) at many locations by 2050,” the study says, even if future emissions of carbon are cut significantly.

“What we are seeing now is enduring and unprecedented change,” said Prof Debra Roberts, a co-chair of an IPCC working group II.

“Even if you live in an inland part of the world, the changes in the climate system, drawn in by the very large changes in the ocean and cryosphere are going to impact the way you live your life and the opportunities for sustainable development.”

The ways in which you may be affected are vast – flood damage could increase by two or three orders of magnitude. The acidification of the oceans thanks to increased CO2 is threatening corals, to such an extent that even at 1.5C of warming, some 90% will disappear.

Species of fish will move as ocean temperatures rise. Seafood safety could even be compromised because humans could be exposed to increased levels of mercury and persistent organic pollutants in marine plants and animals. These pollutants are released from the same fossil fuel burning that release the climate warming gas CO2.

Even our ability to generate electricity will be impaired as warming melts the glaciers, altering the availability of water for hydropower.

Image copyright

Getty Images

The melting of permafrost could add billions of tonnes of CO2 to the atmosphere

Permafrost not so permanent

Huge amounts of carbon are stored in the permanently frozen regions of the world such as in Siberia and Northern Canada.

These are likely to change dramatically, with around 70% of the near surface permafrost set to thaw if emissions continue to rise.

The big worry is that this could free up “tens to hundreds of billions of tonnes” of CO2 and methane to the atmosphere by 2100. This would be a significant limitation on our ability to limit global warming in the centuries to come.

So what happens in the long term?

That’s a key question and much depends on what we do in the near term to limit emissions.

However, there are some warnings in the report that some changes may not be easily undone. Data from Antarctica suggests the onset of “irreversible ice sheet instability” which could see sea level rise by several metres within centuries.

Image copyright

SPL

Climate change might force species to move their ranges

“We give this sea level rise information to 2300, and the reason for that is that there is a lot of change locked in, to the ice sheets and the contribution that will have to sea level rise,” said Dr Nerilie Abram from the Australian National University in Canberra, who’s a contributing lead author on the report.

“So even in a scenario where we can reduce greenhouse gases, there are still future sea level rise that people will have to plan for.”

There may also be significant and irreversible loses of cultural knowledge through the fact that the fish species that indigenous communities rely on may move to escape warming.

Does the report offer some guarded hope?

Definitely. The report makes a strong play of the fact that the future of our oceans is still in our hands.

The formula is well worn at this stage – deep, rapid cuts in carbon emissions in line with the IPCC report last year that required 45% reductions by 2030.

“If we reduce emissions sharply, consequences for people and their livelihoods will still be challenging, but potentially more manageable for those who are most vulnerable,” said Hoesung Lee, chair of the IPCC.

Indeed, some of the scientists involved in the report believe that public pressure on politicians is a crucial part of increasing ambition.

“After the demonstrations of young people last week, I think they are the best chance for us,,” said Dr Jean-Pierre Gattuso.

“They are dynamic, they are active I am hopeful they will continue their actions and they will make society change.”

Follow Matt on Twitter.