I think figure skating has this stereotype as a sport for little girls—that we are these pretty porcelain dolls …

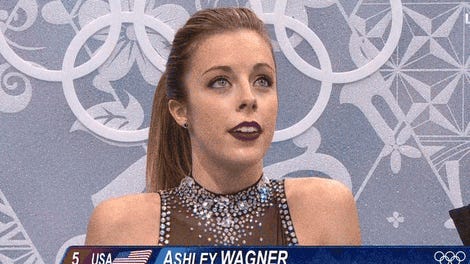

That’s how Ashley Wagner’s “in her own words” story in this year’s edition of ESPN The Magazine’s annual Body Issue begins. The 2016 world silver medalist is one of the athletes featured on ESPN’s list of what elite athletes look like naked. Wagner is featured on the ice in nothing but her boots and blades in what must’ve been an uncomfortably cold photo shoot.

After that opening, Wagner proceeds defensively, saying, “I don’t think people put a lot of thought into the athleticism that goes into the sport.”

Now, I wasn’t in the room when Wagner was interviewed. I don’t know what questions she was asked, whether she volunteered this line of thought, or if the reporter guided her in that direction. But even if she wasn’t prodded towards a defense of figure skating’s athletic bona fides, the fact that Wagner feels the need to make the case that figure skating is hard—grueling, even—speaks to a larger problem about how we speak about sports that have strong feminine associations. Before Wagner can speak about her own body and achievements, she first has to make the case for the athleticism inherent in her sport. Can you imagine a male athlete having to make the case for, say, baseball, like this, over and over again?

You can’t, but when it comes to sports that are associated with women and that are not considered traditionally masculine, athletes are always put in the position of having to defend their sport’s inclusion in the pantheon of athletics, as though if they don’t prove they belong they can be downgraded, like what happened to Pluto’s status as a planet.

Wagner spends the first section of the monologue insisting on the hard work that she and her fellow skaters put into the sport.

I think a lot of people would be very surprised at the kind of training we have to put in. I am on the ice 6 days a week, I am physically training 3-4 hours a day on the ice, off the ice sometimes up to 2 hours a day. This sport is my life. I feel strongly that I’m an athlete through and through.

The detailing of a training regimen for an athlete posing naked in the Body Issue is to be expected; readers want to know how hard these specimens worked to get those bodies, so that we can feel reassured that unless working out is our full-time job there’s no way we can look as good and therefore shouldn’t get off the couch. (I mean, if I can’t look like Ashley Wagner, then why bother?)

But the beginning and end of that quote don’t read as standard; they read as though Wagner imagines herself in conversation with Dude Who Doesn’t Think Figure Skating Is A Real Sport and is feeling the need to defend the validity of her sport and of herself as an athlete. Because if you don’t think you’re speaking with that doubter, then it is not at all surprising to most sports-watchers that an elite athlete works that hard. It’s exactly, in fact, what we’d expect.

Wagner also speaks about her tomboy past in order to bolster her athlete cred. “I was not in this for spandex and the sparkles,” she says.

Okay. If you were into spandex and sparkles and nothing more, I’m pretty sure there would be easier ways to go about getting that fix than spending hours every day on the ice, falling, and getting seriously concussed. (Later in the piece Wagner speaks about the five concussions she has suffered over the course of her career, one of which sounded truly terrifying.) You could, for instance, just buy spandex and sparkles and wear them.

But for a lot of figure skating’s year-round fans—not just those who tune into for the Olympics—costumes and theatricality are part of the appeal of the sport. Why distance yourself from it?

The only reason that makes sense is that you’ve been told, explicitly and implicitly, over and over, that these things have no place in “real” sports. And if you want to identify as an athlete, you are supposed to distance yourself from those things.

(It’s odd, by the way, to hear this coming from someone like Wagner, who is known for her performance ability and how she engages with the music and the audience. She is really good at the performance part of the sport. Her best competitive finish to date—silver medal at the 2016 world championships—was due to her gorgeous, emotional portrayal of Satine from Moulin Rouge. Where Wagner actually struggles quite a bit is on fully rotating her jumps and the speed of her turns. Wagner is no Tonya Harding, the first American woman to land a triple axel, who seemed to be killing time on the ice between jumps and seemed wholly uninterested in the so-called “feminine” aspects of the sport.)

People really don’t need to be told that skating is highly skilled and physically demanding. We’ve all been dragged to an ice rink at least once in our lives and have clung desperately to the boards to keep from falling. I think most of us can extrapolate from that clumsy experience to understand those who are able to glide easily, turn, spin, and jump across the ice are highly skilled, and have worked hard to attain those skills.

It’s a shame that Wagner (and/or the reporter) felt the need to make a case for—apologize for—something that needs nothing of the sort, especially because once you get past it, you’re left with a straight sports story. The rest of the feature was interesting and highly specific to Wagner and the particular traits that make her a compelling world-class athlete: Her grit, her unusual longevity, her recovery from a horrific fall. (Her short-term memory never fully recovered from the experience.) It was the story of a tough-as-nails elite skater, not a defense of skating made to a reader who probably will never be persuaded that skating is really a sport. And really, fuck those people.