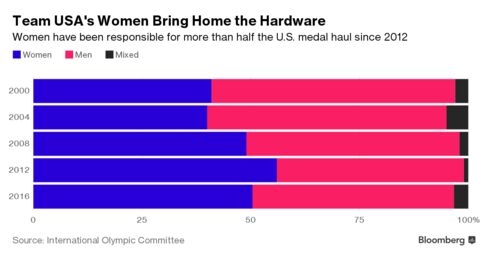

The 2016 Summer Olympics are over, and the women of Team USA won by a landslide. Led by Simone Biles and Katie Ledecky, they won 61 medals, enough to put them at the top of the overall standings, behind China and Great Britain, and more than 25 million Americans turned on their televisions every night to watch them do it.

Sponsors also paid dearly to reach that audience—which, like Team USA’s medal-winners, skews female—and NBC said it will make a profit on these games.

American women’s ability to win and willingness to watch is a singularity in big-time sports. The same audience doesn’t tune in for non-Olympic sports, in spite of the major leagues’ best efforts. Women’s professional sports in the U.S. continue to struggle. And the Olympic athletes who capture the nation’s attention during the games have a small fraction of the financial opportunities that accrue to male sports stars.

The Olympics work for women—and for sponsors, such as Procter & Gamble Co., who are eager to reach them—for a lot of reasons that are hard to replicate. Prime-time network television caters to women in general, and the Olympics’ emphasis on pageantry and personality creates good, competitive drama.

Add the patriotism of global competition on a four-year cycle, said Neal Pilson, who ran CBS Sports for almost two decades, and you’ve got appointment television.

“The sports that are in the Olympics, they’re not being watched because they’re sports, they’re being watched because they’re for flag, for country, for young athletes who strive for four years—you know the stories,” Pilson said.

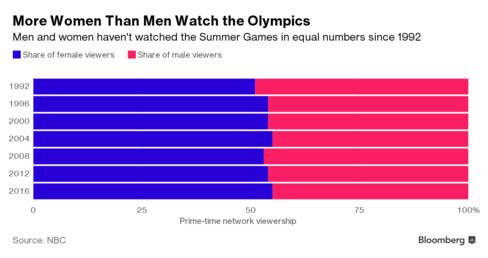

Women made up 55 percent of the audience for the Rio 2016 Games, a proportion that, according to NBC, has been steady for two decades. The Winter Olympics chart even better with women, because figure skating is so popular. Men and women haven’t watched the Olympics in equal proportions since 1992, according to data from NBC.

It’s an attractive demographic, and companies tailor their advertising accordingly. Procter & Gamble came up with the “Proud Sponsor of Mom’’ campaign ahead of the games. Visa Inc. made one ad that featured athletes car-pooling to Rio de Janeiro and another that starred married Olympians Ashton Eaton and Brianne Thiesen-Eaton in mock domestic competition.

“There’s a logic to all this,’’ Pilson said. “Not only will women watch certain programming, but if American athletes are doing well, more women will watch. Very smart people spend a huge amount of money based on this premise.’’

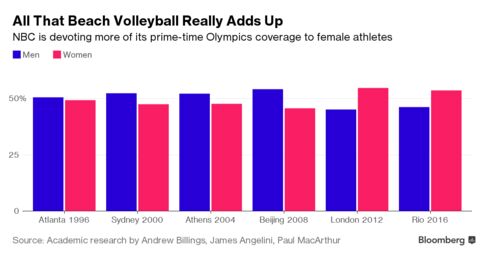

Even though women have made up more than half the viewing audience for decades, Olympics television programming didn’t favor female athletes until recently. Women received more than half the airtime for the first time during NBC’s broadcast of the London 2012 Olympics. This summer, women were featured 60 percent of the time.

“We take great pride in knowing that no one devotes more broadcast network primetime coverage to women’s sports,” said Jim Bell, executive producer of NBC Olympics, in an e-mail. “Our goal is always the same: Show the most compelling television.”

Winning is appealing, so NBC may simply be following the medals. The success in women’s sports is a testament to Title IX, which radically improved the infrastructure for female athletes, and the incentives—college scholarship, anyone?—to succeed.

“It doesn’t surprise me that we would be dominant globally. We’re a well-resourced country with a big population, and we’ve made women’s sports a priority,” said Val Ackerman, commissioner of the Big East conference.

In victory, Team USA’s women gave NBC the kinds of historic moments and emotional storylines for which Olympic telecasts are famous. Biles established herself as one of the best gymnasts in history; Ledecky set two world records en route to four golds and one silver medal, the best performance by an American woman in a single Olympics. Simone Manuel became the first African-American to win a gold medal in an individual swimming event. Sarah Robles won America’s first medal in weightlifting in 16 years, Claressa Shields was the first American to defend a medal in boxing and Allyson Felix became the most-decorated female track-and-field athlete in U.S. Olympic history.

The same kind of storytelling doesn’t translate to long league seasons, either for women’s sports or men’s. In the major leagues, stars are celebrities and often multimillionaires, with careers that don’t lend themselves to the Olympic-style mini-biopic.

If marketers really want to reach women, they have to get more creative, said Amy Trask, former chief executive officer of the Oakland Raiders and author of the new book, You Negotiate Like a Girl. “More sophisticated and sensible strategies are needed than ‘shrink it and pink it,’’’ she said.

The majority of money in professional sports is made by selling broadcast rights, and while the U.S. women’s soccer team has sold out exhibition games, there’s been little audience for women’s sports on television. Women don’t tend to watch TV when sports are on—during the day on weekends. In prime-time, research suggests women gravitate toward entertainment over sports.

This creates a chicken-or-egg problem. Outside the Olympics, the biggest sponsors largely ignore female athletes. But without investment, it’s hard to create a critical mass of fans. Companies are missing a chance to stand out, said Dominic Curran, CEO of sports marketing agency Synergy.

“More brands should be looking at the opportunity in women’s sport,’’ he said. “People have to take the plunge, not based on the numbers but around the opportunity to talk to what is potentially a huge audience.’’